Coracles at Cilgerran

Roy Kerridge

Cardigan Castle, which overlooks the River Teifi, is surrounded by bram- bles. A tower has been converted into a manor house, but any Welsh Sleeping Beauty inside would catch her death, for the windows gape vacantly on the world below.

`Yes, the owner's in hospital now', my landlady told me. 'The council have been trying to get her out for some time, as they Want to get their hands on the castle. It's their fault — they were offered it for nothing years ago, and turned it down. Now they're offering the lady a council caravan if she'll move. A caravan! Did you ever hear of such a thing? They hate her for keeping them out of the castle, you see. She's on social security now. People say there's a tunnel under the castle, leading to the other castle at Cilgerran.' Cilgerran, a village further along the dark green river, is well worth tunnelling to, as I found next day. Perched on the edge of a gorge, where primeval forests of oak and ash grow on sheer slopes between the river and the fields above, it is the scene of the Annual Coracle Races and Aquatic Sports, held at the end of August. Crowds were hurrying down to the banks as I arrived, their way barred between cottages by sturdy fishermen selling tick- ets. Others climbed onto the battlements of one of the most romantic castle ruins I have seen, built straight up from a crag that towered above the trees, the masonry seeming to grow naturally from the jagged rocks. For myself, I retired to the dark, ciavernouLdepths of the mediaeval Pendre Inn, where the flagstone floor shone with soap and water. Two men at the bar were discussing coracles so I introduced myself. They proved to be the announcers, Mr Davies and Mr Griffiths, both eager to tell me all about the races.

The coracle is one of the oldest boats in the world', I was told earnestly. 'It's been used for salmon fishing here for over two thousand years, before the Romans came. Only three rivers in the world have coracle fishers on them now — the Teifi, the Towy at Carmarthen and the Severn at Iron Bridge. Our Teifi coracles are heavier boats altogether than those on the Towy and they're harder to . handle. We make them in the same way that we've always done, out of willow and hazel, only now we stretch calico covered in pitch over the frame, instead of animal skins. These aquatic sports began in the year they had the Festival of Britain, and we've kept them up ever since.'

From the castle walls I admired a view that had scarcely changed since the first Welshman had paddled down the river in his coracle, past wolves that prowled among the sessile oaks. Then I stopped at a cottage door to chat to a friendly old lady, Mrs Bevan, who advised .me to marry a local girl, but didn't say which one. She tried to teach me Welsh pronunciation without much success.

`Yes, I've lived in Cilgerran all my life', she said. 'You people drove us all into Wales, you know. Your ancestors did, I mean.'

Judging by their descendant, I doubt if my ancestors could have done anything so decisive. In their place, I would have settled at Cilgerran and chased anyone who objected into England.

'A pack of wolves escaped from the wild life park not long ago', Mrs Bevan con- tinued. 'We all hid indoors until they were shot. The last wolf stayed loose for ever so long. They were starving, people say, and leaped over the fence.'

From the river, a starting pistol could be heard, fired, as it happened, by Mr Grif- fiths himself. The first two events were children's swimming races. It was a hot day, and the crowds of families sitting on the grass and eating sandwiches made a colourful sight. Welsh cakes, tea and other dainties were being sold from a stall in a place where the rocky gorge had been broken by a stretch of grassland to form an ideal setting. From a platform, Mr Davies commanded a powerful loudspeaker. The coracles were off!

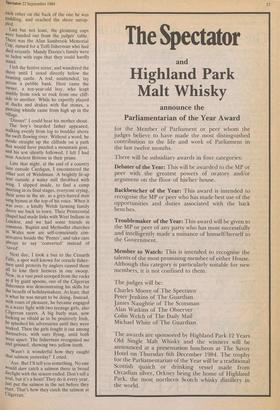

Two ropes had been stretched above the river, a starting and a finishing line. Three black coracles, each with an affable Welsh- man inside, bobbed about alongside the starting rope. Other coracles lay on the bank like turtle shells. When their owners picked them up, the effect was of a giant tortoise on its hind legs. A deep pudding basin of a boat, five feet long, a coracle is carried on the back. The calico sides are

'Jim spent so much time there, he decided to go down with it'

bendy, and the shape is oval, with a slight bluntness at the bows. One wooden seat spans the craft, and only one oar is used. Salmon fisherman can dart across rock pools and shallows with ease, hopping out to lift the boat over sandbanks, boulders and tree trunks when necessary.

Holidaymakers from England - watched in fascination as the pistol cracked and the boatmen charged forwards, stabbing the water in front of them again and again, their heads down, teeth clenched and eyes popping. Three abreast, they buffaloed through the water, leaning over the bows like furious figureheads, as the oars plunged up and down. Roars of triumph greeted the winner. I made my way to Tough Egg Corner, as I named the stretch of bank near the starting line, where gnarled fisherman and their cheerful fami- lies sat cracking jokes in Welsh beside their boats. As race followed race, money changed hands, and bets of ten to 15 pounds were made. These were the ribald Welsh, the ones who don't go to chapel.

Nobody I spoke to was a full-time salmon fisherman, and I doubt if such a breed exists nowadays on the Towy or the Teifi.

'I'm a sea fisherman, and the coracle fishing is only part-time', one man told me. 'Coracles are a hobby now, as the salmon fishing has declined so terribly.'

However, a salmon was being raffled, and ticket sellers walked up and down the bank. Standing apart from the crowds, Tracey Williams, the Coracle Queen, smiled elegantly at her subjects. Flanked by her royal attendants, Sharon and Bever- ley, she told me that she was 13 years old, and had been chosen at a special beauty contest. Her coronet sparkled in the sun, and she wore a patriotic sash of red, white and blue. Another notable young lady was Mandy Davies, a boyish girl in shorts and blue denim, with shark tooth earrings bought at Cardigan Market. Equally adept at swimming and coracle-racing, she seemed to win every event she entered, and did so every year, I was told. Her father was a fisherman. Race followed race with such rapidity that the results were announced as the next event was in prog- ress. Twelve-year-old boys and teenagers swam and steered coracles alternately, everyone brimming with health and high spirits.

On the far bank of the river, a long greasy pole with a balloon on the end protruded from the forest. Small children in swimsuits shrieked and giggled as they tried to walk to the balloon but fell in the river instead. Everyone here could swim, but a rescue boat patrolled in case of accidents.

Coracles are not built for racing, and I preferred to watch them skim carelessly back to shore at their own speed when a race was over, rivalling the nearby swans in gracefulness. A rowing boat overloaded with 12 teenagers sauntered about on the edge of the proceedings for a while, until the diving competitions began. Then one

by one the youngsters hopped into the Teifi and disappeared, to rise minutes later a long way downstream. Sometimes the soles of their feet broke the surface during these salmon-like streaks along the river. The races lasted for nearly four hours, the halfway mark distinguished by a ceremo- nial glide-past of the Royal party.

One race, 'for licensed coracle fishermen only', aroused great excitement at Tough Egg Corner. `Come on Bill! I've got a pound on him, five to one', a bearded young man shouted. It's a Steward's Inquiry', he exclaimed in disgust, when the race was over. How- ever, Bill had won, and the crinkled notes were paid over grudgingly by a stout man with an equally crinkled face. The punter kissed the money flamboyantly, not know- ing that when you kiss money, you kiss it goodbye.

`Thieving bastard', the other man mut- tered.

`Note the superiority of the Cilgerran coracle', the announcer declared. He seemed highly conscious of the difference, invisible to myself, between the Teifi coracle and the lesser Towy article.

A surprise item came next. `And now, ladies and gentlemen, we are having a dummy trawl to show you how the Teifi fishermen catch the elusive salmon. This is only a demonstration, for no salmon has ever been caught on this stretch of the river. However, if by chance they do catch one, it will be the prize in the raffle instead of the one we've raffled already.'

Two fishermen, one red-faced and ex- cessively ribald, the other craggy, carried their coracles to the bank, grimacing broadly. When the announcer repeated that no salmon had ever been caught here, they began to laugh. Now, for the first time, I could see coracles used as the Ancient Britons intended them to be. Each man paddled along the river on the bank opposite his partner. One hand held the oar, the other clutched one end of a long trawl net. So between them, they could sweep the Teifi.

`Here they come, slowly, painstakingly, hoping against hope', the loudspeaker crackled melodramatically. Suddenly there was a splash, and both boats flew like minnows towards one another. The net was raised, and there was an enormous salmon!

Crowd and announcer went wild, and the men triumphantly held the great silver fish aloft by the tail. It was at least three feet long, and had died with surprising suddenness. On shore, a photpgrapher from a local paper, went into a frenzy of picture-taking, posing a small girl beside the sheepishly smiling men and their trophy.

The sports ended with displays of trick coracle riding by local youngsters. Towing an empty boat, one boy would somersault from coracle to coracle and back again, and finally lift the extra boat over himself like a clam in a shell. A young man balanced three empty coracles on top of

each other on the back of the one he was paddling, and reached the shore untop- pled.

Last but not least, the gleaming cups were handed out from the judges' table. There was the Alan Sambrook Memorial Cup, named for a Teifi fisherman who had died recently. Mandy Davies's family were so laden with cups that they could hardly stand.

I left the festive scene, and wandered the shore until I stood directly below the looming castle. A rod, unattended, lay across a pebble bank. Here came the owner, a ten-year-old boy, who leapt nimbly from rock to rock from one cliff- side to another. While he expertly played at ducks and drakes with flat stones, a piercing whistle came from high up in the village.

`Dinner!' I could hear his mother shout.

The boy's bearded father appeared, walking evenly from log to boulder above the swift flowing river. Without a word, he strode straight up the cliffside on a path that would have puzzled a mountain goat, and his son silently followed. I felt I had seen Ancient Britons in their prime.

Late that night, at the end of a country lane outside Cardigan, I encountered the other sort of Welshman. A brightly lit-up tent outside a water mill throbbed with song. I slipped inside, to find a camp Meeting in its final stages, everyone crying, their arms in the air, as a grey-haired man sang hymns at the top of his voice. When it was over, a kindly Welsh farming family drove me back to town. Their Pentecostal chapel had made links with West Indians in London, and we had some friends in

common. Baptist and Methodist churches 10 Wales now are self-consciously con-

servative beside the `Pentes', and take care always to say 'converted' instead of `saved'.

Next day, I took a bus to the Cenarth Falls, a spot well known for coracle fisher- men until protests by anglers caused them all to lose their licences in one swoop. Now, in a vast pool scooped from the rocks as if by giant spoons, one of the Cilgerran fishermen was demonstrating his skills for the benefit of holidaymakers. At least, that Is what he was meant to be doing. Instead, With roars of pleasure, he became engaged In a water fight with two teenage girls, also Cilgerran racers. A big burly man, now looking so ribald as to be positively Irish, he splashed his adversaries until they were soaked. Then the girls fought it out among themselves, with oars flying, until both Were upset. The fisherman recognised me and grinned, showing two yellow teeth.

'Wasn't it wonderful how they caught that salmon yesterday!' I cried.

`Aye. But I'll tell you something. No one Would dare catch a salmon there in broad daylight with the season ended. Don't tell a soul, but it's a hoax! They do it every year, lust put the salmon in the net before they start. That's how they catch the salmon at Cilgerran.'

Previous page

Previous page