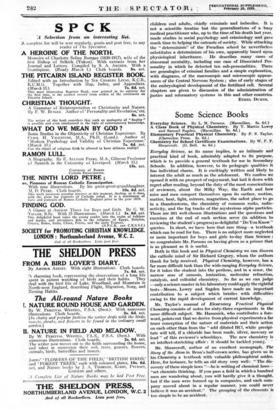

Some Science Books

Everyday Science, as its name implies, is an intimate and practical kind of book, admirably adapted to its purpose, which is to provide a general textbook for use in Secondary Schools. In addition, however, to its pedagogic qualities it has individual charm. It is excitingly written and likely to interest the adult as much as the adolescent. We confess we opened it with no prospect of enjoyment, but laid it down with regret after reading, beyond the duty of the most conscientious of reviewers, about the Milky Way, the Earth and how mice and men comport themselves upon its surface, motion, matter, heat, light, mirrors, magnetism, the safest place to go in a thunderstorm, the chemistry of common rocks, radio- activity, and the fog tracks of the mysterious alpha particles. There are 381 well-chosen illustrations and the questions and exercises at the end of each section serve (in addition to reviewing the student's progress) as delightful "Do You Know " queries. In short, we have here that rare thing-a textbook which can be read for fun. There is no subject more neglected or more important for boys and girls to-day than Science : we congratulate Mr. Parsons on having given us a primer that is as pleasant as it is useful.

Both in this book and in Physical Chemistry we can discern the catholic mind of Sir Richard Gregory, whom the authors thank for help received. Physical Chemistry, however, has a far more difficult task than the wide-ranging Everyday Science, for it takes the student into the perilous, and in a sense, the narrow seas of osmosis, ionization, molecular refraction, catalysis, and colloidal chemistry. So far as we can judge -only a science master in his laboratory could apply the rightful tests-Messrs. Lowry and Sugden have made an important contribution to a subject which bristles with difficulties owing to the rapid development of current knowledge.

Mr. Taylor's manual of Elementary Practical Physical Chemistry consists of notes for sixty-three experiments in the same difficult subject. Mr. Bernick, who contributes a fore- word, points out that we derive from physical experiments a far truer conception of the nature of materials and their action on each other than from the " add diluted HCI, white precipi- tate will tell, if a chloride has been made, silver, mercury or lead " of this reviewer's schooldays. The new chemistry is an intellect-stretching affair : it should be tackled young.

Mr. Shearcroft, author of an excellent monograph, The Story of the Atom in Bern's half-crown series, has given us in his Chemistry a textbook with valuable philosophical asides. Here, for instance, he tells an old story very well : " The dis- covery of these simple laws "-he is writing of chemical laws- "set chemists thinking. If you pass a field in which a hundred men are wandering about, you will hardly give it a thought, but if the men were formed up in companies, and each com- pany moved about in a regular manner, you could never believe it was an accident." The grouping of the elements is too simple to be an accident.

Previous page

Previous page