One-legged super-tramp

Peter Quennell

Osbert Sitwell has told us, among his memories of literary London, how, if W. H. Davies visited him at his pleasant house in Chelsea, although the middle- aged poet had lost the better half of one leg, he always refused to travel by public transport and would stump the whole way from Bloomsbury on foot. The mishap that must frequently have exasperated, but was never allowed to cripple, a man who called himself the 'Super-Tramp', occurred in 1899, when, during an expedition around Canada, he had attempted to board a moving freight-train, his foot slipped and a wheel had completely severed his right ankle. 'Even then', he wrote in his auto- biography, did not at first know what had happened', until he tried to stand upright and failed; and, while he awaited help, he decided that the best method of keeping 'a calm face' was to sit and smoke his pipe — conduct, he reported with pride, that both impressed the crowd of curious spectators and 'caused much sensation in the local press'.

Davies was one of the oddest, and certainly the toughest and most courageous, of the early 20th-century Georgian poets. Well aware that he posses- sed unusual gifts, now that his body had let him down, he determined that his brains should have the chance they needed and deserved. He therefore travelled on a cattle-boat back to England, and, having an unearned income of eight shillings a week, lived frugally in a series of London lodgings, where he composed a blank verse tragedy and over 100 sonnets that editors and publishers immediately refused. His next plan, at the beginning of the new century, was to have two or three poems printed on two thousand sheets- of paper, which he vainly hoped to sell from door to door. English poets, at that time, were a more homogeneous, and perhaps more generous-minded band than, it seems, they are today; and although almost all of them inhabited country cottages, they regularly met, under the aegis of Edward Garnett, at . a Soho restaurant named the Mont Blanc. The table they reserved there was the scene of protracted literary discussion; they took a keen interest not only in one another's work but in the promise shown by newcomers, and quickly welcomed Davies as the protégé of Edward Thomas, an unusually gifted poet himself, who had reviewed his earliest book.

That collection, The Soul's Destroyer and Other Poems, which appeared in 1905, attracted other favourable reviews, while the free copies he had posted to disting- uished contemporaries, including Bernard Shaw and Arthur Symons, once the histo- rian of the French Symbolists and now the last luminary of the British fin-de-siecle, were acknowledged with appreciative let- ters. Symons intoned his praises; and Shaw despatched a sum of money that would enable him, he said, to send additional copies to any 'critics or verse-fanciers he knew of, wondering (he added) whether they would recognise a poet when they met one'. Edward Thomas remained a staunch champion. Besides having a new wooden leg built for the poet by his local village wheelwright, about the same time he provided him with friendly introductions to Walter de la Mare, Masefield, Belloc, Conrad and W. H. Hudson.

Thenceforward, Davies never lacked supporters; and the appearance in 1908 of The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp, heralded by Shaw's enthusiastic preface it was Shaw who had suggested the title, and Mrs Shaw who had helped pay the printer — finally brought him to the attention of the ordinary reading public. In 1912, the earliest volume of Georgian Poetry edited by that golden-hearted en- thusiast, Edward Marsh, published five of Davies's poems — his companions were Rupert Brooke, Walter de la Mare, D. H. Lawrence and Harold Monro. Meanwhile, a year later, thanks to Thomas and Gar- nett, and, incidentally, to the good taste of H. H. Asquith, Marsh's old friend and the current Prime Minister, he had been awarded a Civil List pension of £50 per annum.

On his death in 1940, then happily married to a sympathetic country girl, the heroine of a candid prose-narrative he entitled Young Emma --, its frankness dismayed Shaw, who advised its suppres- sion — he was still a well-known poet. But I doubt if many lovers of poetry born since the Second World War are, except for a few often anthologised pieces, now famil- iar with the full contents of his 20 books of verse. Yet Davies was a far more interest- ing character than some of his Georgian contemporaries. The rustic moods they affected were apt to try the reader's pati- ence — for example, when a certain poet described a pensive walk across the fields, during which he had

Leaned upon a gate and talked A little with a lonely lamb

— lines that used to rouse the ageing Sir Edmund Gosse to a positive frenzy of amusement and old-gentlemanly derision.

Davies had a sharper and rougher gift. Though he loved the country as much as his delightful predecessor Robert Herrick, whom he now and then resembled — both loved to write about themselves, their domestic surroundings and the attractive girls they knew — he despised sentimental rusticity and was haunted by grim recollec- tions of his vagrant early years. Like Herrick, too, at his best he had a wonder- fully acute eye — a quality that won the approval of a modern poet, Philip Larkin. Davies, Larkin recently wrote in a review, `possessed the knack of suddenly unearth- ing . . . some hitherto unnoticed detail or irony or pleasure and extending it for our enjoyment . . . Davies never lost the power to refresh the commonest experi- ence.'

His Selected Poems, chosen by Jonathan Barker, illustrate many different aspects, good and bad, of his poetic constitution. Some occasional verses, such as his lugub- rious address to whisky, are evidently rather poor stuff:

Whisky, thou blessed heaven in the brain, 0 that the belly should revolt, To make a hell of afterpain, And prove thy virtue was a fault!

But elsewhere I rediscovered a poem one that has stuck in my mind for a half a century at least, and that Larkin particular- ly praises with special reference to the vivid closing image:

While every bird enjoyed his song, Without one thought of harm or wrong I turned my head and saw the wind, Not far from where I stood, Dragging the corn by her golden hair, Into a dark and lonely wood.

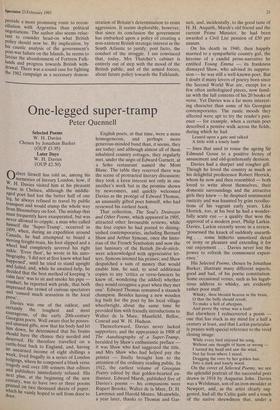

On the cover of Selected Poems, we see the splendid portrait of the successful poet drawn in 1918 by Augustus John. Davies was a Welshman, son of an iron-moulder at Newport, and, as the artist clearly sug- gested, had all the Celtic guile and a touch of the native shrewdness that, under a mask of engaging bohemianism, we associ- ate with Dylan Thomas. Later Days is the autobiographical book that completed the Super-Tramp. Prose was not the poet's strongest suit; but it inchicles some admir- able sketches of his fellow writers. Ralph Hodgson, he says, 'was a man to my own mind' because he smoked shag, and 'pre- ferred to talk of dogs and prize-fighters instead of poetry and poets'. As for Rupert Brooke, 'I was always struck by his sound commonsense . . . On one occasion when he had repeatedly mentioned the name of a certain great lady . . . I told him that it might be necessary — if he was to become a great author — to hear the opinions of Matilda Jane Ann and Doll Tearsheet'; and the spoiled young man had readily agreed.

Equally illuminating are Davies's tales of his adventures in the houses of the rich. Between 1914 and 1918, he was again and again invited to recite his poems before a fashionable audience, and would cheerful- ly oblige. He was a 'very shy man' he confesses; but after all, he reflected, though 'people might say I was a very bad reader, they would not be able to say I was a very bad poet'. The indomitable Lady Cunard, beloved by George Moore, was characteristically expansive. 'That man there', she exclaimed, 'writes beautiful poetry'; to which Arthur Balfour 'almost impatiently' replied, 'Don't talk to me of the work of Davies, for I know it far better than you do.' Yet the flattery and applause of the great world could not diminish his good-hearted acceptance of life, whether it were painful or pleasurable, nor could it change his customary habits. If he wanted love, he once told Robert Graves, it was to the East End he invariably returned.

Previous page

Previous page