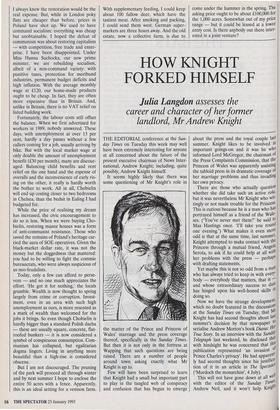

TIME TO EVICT THE BATS

Radek Sikorski reports on the

successes and setbacks in his plans to restore a Polish manor house

Dw6r Chobielin IT IS NOW almost four years since my gamily bought Dwor Chobielin, a derelict Manor house in western Poland. I wanted to restore it, to cleanse it of the literal and metaphorical filth of 45 years of commu- stn. As I reported in The Spectator in ,',989, I hoped to get the job done by 1992, 'or the price of a poky London flat'. We have made progress. Our guests Marvel at the transformation. When we bought it, the keeper's lodge was a shell, With windows and doors wrenched out. Sand mixed with excrement lay where ahugany floorboards used to be. Now, it Is. our temporary family home. Steel girds Its fragile frame, red tile has replaced the asbestos on the roof, and an almost perfect lawn (planted with English grass seed) has Stifled the weeds and brambles which pre- viously enveloped the ruin. Gleaming White paint and brass fittings have taken the place of peeling plaster and rotting door frames. The improvement is particu- larly striking as you approach from the drive. After half a century of neglect, elm and maple trees have been pruned, and the weeds between them pulled up. Over several weekends, using spades and a pow- erful hose, my wife and I cleared ten inch- es of silt from the original cobblestones. els autumn we planted a row of 50 chest- nuts to complement the other side of the avenue.

.Our sense of belonging has lately been ,relnforced: we've been burgled. A few flours absence — to attend a family funer- a,.l. — was enough for thieves to smash a kitchen window. To our relief, they took „°,11Aly a portable television, a VCR and an "iu ghetto-blaster. My word processor, a collection of old maps and silver cutlery elicited no interest. Apparently, such things are hard to sell on the local market. While the lodge now feels like home, the Manor itself has a long way to go. In the Past, the peasant families who squatted there had an interest in damaging it. If `tiney could prove that the structure was n.lisafe, the local council was obliged to eve them a flat in town, in the Corbusieri- :11 Concrete tenements to which they aspired. From their point of view it made perfect sense to punch holes in the roof, so that rain-water could penetrate more easily and damage the rafters. It became apparent how badly they had weakened the structure only when we started rebuilding. We took off the roof, and the first-floor beams proved rotten beyond repair; we took off the first-floor beams, and one of them, as thick as the Iraqi supergun, fell through the brick arch of the cellar. In the end, we were left with only the outside walls. It would have been much cheaper to build the house from scratch. The expense of deconstructing the house, so to speak, was much greater than the value of the materials.

Finally, we put the roof back on — after a year's work. We ran short of original reddish-orange tiles. Fortunately for us, a cottage near the 19th-century factory where they were made (of which only a huge chimney remains) had just been pulled down, so we could match the miss- ing 100 pieces. Then we found a crafts- man, employed by a local state-owned building company, who was willing to lay tiles after hours. All summer he worked almost every afternoon, sometimes past dusk, making and fastening the gutters and sheeting. By the time he had finished laying tiles, just before the first frosts, a ton of copper had gone under his wooden ham- mer.

So I did not finish the house in time for the Single European Market. It looks handsome enough from afar. Four Tuscan columns support a traditional neo-classical porch and the mellow tiles on the high- pitched roof stand out sharply against the greenery of the park behind. When the workers keep warm by burning wood in the fireplace and smoke issues from the chim- ney, you might think the house was already inhabited. But inside, bare bricks, steel beams and concrete floor still form the drawing-room. In the kitchen, pipes and wires poke out of the walls where an Aga and the washbasin are supposed to go. The windows are still boarded up with timber and new ones are not even ordered. The only residents in the upstairs bedrooms are a family of bats. As for the garden, only a third of the wall has been completed. When the weather is good, crowds from half the county come and gape at my moth- er weeding the cabbage patch. She feels like a rare specimen in a zoo.

I admit I did not quite meet the targeted cost either. The ruin cost under /1,000 and

Mind your language

WHAT is strife?

Why, internecine, of course (in terms of a cliché), especially in Bosnia, to judge by reports on the radio.

And what does internecine mean? According to a classicist friend of mine it means murderous, and has nothing to do with reciprocal action. The Oxford English Dictionary supports this, defin- ing internecine war as 'war for the sake of slaughter, war of extermination, war to the death'. It adds, in commenting on the rare word intemecion, 'improperly mutually deadly conflict'.

The difficulty is that, in Latin, intemecare means to destroy, and the element inter (as in interire, to perish) does not have the meaning of mutual behaviour, as in intercourse, or interna- tional. Yet, to us English, inter always does suggest mutuality.

This brings us to what has been called 'the etymological fallacy' — which is to say, that words mean what they used to in old languages. They don't though, nor do they mean what they meant in our mothers' times.

So, if you're a classicist, watch your step. Oh, and by the way, Dr Johnson defined internecine in 1755 as 'endeav- ouring mutual destruction'.

Dot Wordsworth

I always knew the restoration would be the real expense. But, while in London poky flats are cheaper than before, prices in Poland have shot up. We used to have command socialism: everything was cheap but unobtainable. I hoped the defeat of communism was about restoring capitalism — with competition, free trade and enter- prise. I have been disappointed. Under Miss Hanna Suchocka, our new prime minister, we are rebuilding socialism, albeit of a non-command variety: with punitive taxes, protection for moribund industries, permanent budget deficits and high inflation. With the average monthly wage at £120, our home-made products ought to be cheap. In fact, they are often more expensive than in Britain. And, unlike in Britain, there is no VAT relief on listed building work.

Fortunately, the labour costs still offset the balance. When we first advertised for workers in 1989, nobody answered. These days, with unemployment at over 13 per cent, hardly a day passes without a few callers coming for a job, usually arriving by bike. But with the local market wage at only double the amount of unemployment benefit (£30 per month), many are discour- aged. Balancing child benefits and rent relief on the one hand and the expense of overalls and the inconvenience of early ris- ing on the other, it really is hardly worth the bother to work. All in all, Chobielin will end up costing closer to two bedrooms in Chelsea, than the bedsit in Ealing I had budgeted for.

While the price of realising my dream has increased, the civic encouragement to do so is less. When we were buying Cho- bielin, restoring manor houses was a form of anti-communist resistance. Those who saved the remains of Poland's heritage car- ried the aura of SOE operatives. Given the black-market dollar rate, it was not the money but the doggedness that mattered: you had to be willing to fight the commie bureaucrats, who were always suspicious of us neo-feudalists.

Today, only a few can afford to perse- vere — and no one much appreciates the effort. 'He got it for nothing,' the locals grumble. Wealth is now thought to spring largely from crime or corruption. Invest- ment, even in an area with such high unemployment as ours, is more resented as a mark of wealth than welcomed for the jobs it brings. So even though Chobielin is hardly bigger than a standard Polish dacha — these are usually square, concrete, flat- roofed bunkers — it is now considered a symbol of conspicuous consumption. Com- munism has collapsed, but egalitarian dogma lingers. Living in anything more beautiful than a high-rise is considered obscene.

But I am not discouraged. The pruning of the park will proceed all through winter and by next summer I hope to enclose the entire 50 acres with a fence. Apparently, this is an ideal setting for a venison farm. With supplementary feeding, I could keep about 100 fallow deer, which have the tastiest meat. After smoking and packing, I could send them west. German super- markets are three hours away. And the old estate, now a collective farm, is due to

come under the hammer in the spring. The asking price ought to be about £100,000 for the 1,000 acres. Somewhat out of my price range — but it could be leased at a lower entry cost. Is there anybody out there inter- ested in a joint venture?

Previous page

Previous page