THE COLD WAR'S DEADLIEST SECRET

Mark Urban reveals the Russians' plans to bombard the West with lethal viruses, and speaks to the man behind them

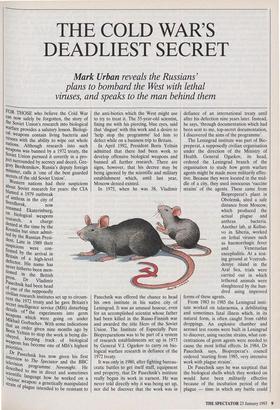

FOR THOSE who believe the Cold War can now safely be forgotten, the story of the Soviet Union's research into biological Warfare provides a salutary lesson. Biologi- cal weapons contain living bacteria and viruses with the ability to wipe out whole nations. Although research into such weapons was banned by a 1972 treaty, the S. oviet Union pursued it covertly in a pro- ject surrounded by secrecy and deceit. Gre- gory Berdennikov, Russia's deputy foreign minister, calls it 'one of the best guarded secrets of the old Soviet Union'. Western nations had their suspicions about Soviet research for years: the CIA blamed a 1979 outbreak of anthrax in the city of Sverdlovsk, now renamed Ekaterinburg, on biological weapons research, a charge denied at the time by the Kremlin but since admit- ted by the Russian Presi- dent. Late in 1989 their suspicions were con- firm. ed by the arrival in Britain of a high-level defector. His name has never hitherto been men- tioned in the British press. Dr Vladimir Pasechnik had been head of one of the supposedly civilian research institutes set up to circum- vent the 1972 treaty and he gave Britain's secret intelligence service (MI6) disturbing details of ' the experiments into germ weapons which were going on under Mikhail Gorbachev. With some indications that an order given nine months ago by Boris Yeltsin to stop the work is being dis- obeyed, keeping track of biological weapons has become one of MI6's highest Priorities. . Dr Pasechnik has now given his first interview to The Spectator and the BBC oescdescribed programme Newsnight. He ribed to me in direct and sometimes c!e.ntific language how he worked on a svtielous' weapon: a genetically manipulated rain of plague intended to be resistant to the anti-biotics which the West might use to try to treat it. The 55-year-old scientist, fixing me with his piercing, blue eyes, said that 'disgust' with this work and a desire to 'help stop the programme' led him to defect while on a business trip to Britain.

In April 1992, President Boris Yeltsin admitted that there had been work to develop offensive biological weapons and banned all further research. There are signs, however, that his . decree may be being ignored by the scientific and military establishment which, until last year, Moscow denied existed.

In 1975, when he was 38, Vladimir Pasechnik was offered the chance to head his own institute in his native city of Leningrad. It was an unusual honour, even for an accomplished scientist whose father had been killed in the Russo-Finnish war and awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. The Institute of Especially Pure Biopreparations was to be part of a system of research establishments set up in 1973 by General V.I. Ogarkov to carry on bio- logical warfare research in defiance of the 1972 treaty.

It was only in 1980, after fighting bureau- cratic battles to get itself staff, equipment and property, that Dr Pasechnik's institute really began its work in earnest. He was never told directly why it was being set up, nor did he discover that the work was in defiance of an international treaty until after his defection nine years later. Instead, he says, 'through documentation which had been sent to me, top-secret documentation, I discovered the aims of the programme'.

The Leningrad institute was part of Bio- preperat, a supposedly civilian organisation under the direction of the Ministry of Health. General Ogarkov, its head, ordered the Leningrad branch of the organisation to study how germ warfare agents might be made more militarily effec- tive. Because they were located in the mid- dle of a city, they used innocuous 'vaccine strains' of the agents. These came from Biopreperat's plant in Obolensk, sited a safe distance from Moscow, which produced the actual plague and anthrax bacteria. Another lab, at Koltse- vo in Siberia, worked on lethal viruses such as haemorrhagic fever and Venezuelan encephalitis. At a test- ing ground at Vozrozh- deniye island in the Aral Sea, trials were carried out in which tethered animals were slaughtered by the hun- dred using improved forms of these agents.

From 1983 to 1985 the Leningrad insti- tute worked on tularaemia, a debilitating and sometimes fatal illness which, in its natural form, is often caught from rabbit droppings. An explosive chamber and aerosol test rooms were built in Leningrad to discover, using vaccine strains, what con- centrations of germ agents were needed to cause the most lethal effects. In 1984, Dr Pasechnik says, Biopreperat's council ordered 'starting from 1985, very intensive work with plague strains'.

Dr Pasechnik says he was sceptical that the biological shells which they worked on would have been militarily effective because of the incubation period of the plague — time in which any battle could have been won or lost. Using plague bombs on a city of 100,000 inhabitants, however, he says, 'about half of its population will be killed', leading to 'panic on the national scale'.

The former director says that Biopreper- at's council also discussed 'subversion activ- ity': using strains like pneumonic plague to be released by special forces or terrorists in undeclared wars. 'Terrorists might intro- duce it in any city and then deny it,' he says. Naturally occurring diseases provide countries prepared to use them as weapons with a more easily deniable form of mass destruction than nuclear or chemical weapons.

When British and American leaders put allegations about the covert programme to Mikhail Gorbachev at various summit meetings, he flatly denied that the Soviet Union pursued research into offensive bio- logical weapons. Today, British diplomats are too polite to accuse him directly of lying, but some officials at the Russian for- eign ministry in Moscow say that is precise- ly what happened.

Biopreperat had 25,000 employees and a budget of 100 million roubles each year in the 1980s: Dr Pasechnik believes that in the Soviet command system many high-ranking officials must have known its real purpose. It strains credibility to suggest that Mr Gorbachev did not demand and receive explanations about what was going on fol- lowing repeated representations on the subject from British and American leaders. Until the August 1991 coup, Mr Gorbachev replied to these Western requests simply by saying he would look into the matter.

President Yeltsin's April 1992 decree, confirming that it was an offensive weapons programme, was applauded in London and Washington. Several months later Russian foreign ministry officials handed a declara- tion to the United Nations confirming that the research had gone on in several places, including Leningrad, Obolensk and Koltse- vo. With the simple certainty of bureau- crats schooled in the communist system, they asserted blankly that all work on the offensive programme had stopped on the day of the President's decree.

There is evidence, however, that even in the new Russia deceit about the biological weapons programme is continuing and that Biopreperat is not fully under the govern- ment's control. On 24 August 1992, Dou- glas Hurd, the British Foreign Secretary, and Lawrence Eagleburger, US Secretary of State, wrote a private letter to Andrei Kozyrev, their Russian opposite number. I have obtained a copy of the correspon- dence, in which Messrs Hurd and Eagle- burger state, 'We are very concerned that some aspects of the offensive biological warfare programme, which President Yeltsin acknowledged as having existed and which he then banned in April, are in fact being continued covertly and without his knowledge.'

They add, 'This issue could undermine the confidence in the US and UK's bilater- al relationships with Russia.' A few weeks after the letter, Britain, Russia and the United States concluded an agreement allowing for inspections of suspected bio- logical warfare establishments, another step applauded in the respective foreign ministries.

Douglas Hogg, the Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, welcomes the efforts of the Yeltsin govern- ment but notes that `we have some infor- mation from some sources' which suggests that the President's decree may not be being observed. Mr Berdennikov admits frankly that the Russian foreign ministry does not really know what is going on in Biopreperat. 'When we speak to those peo- ple they say "no". So what can we do?'

Dr Pasechnik says that experiments designed to develop antibiotic-resistant plague had not been successfully concluded when he defected in 1989. However, the August 1992 Hurd/Eagleburger letter stat- ed that work was underway to 'allow indus- trial production of a strain of plague resistant to cold and heat and to 16 antibi- otics — for offensive purposes'. It is appar- ent that MI6 and the CIA are devoting a great deal of effort to finding out what is happening in Biopreperat and may well have succeeded in recruiting sources in it after Dr Pasechnik's defection.

Western diplomats appreciate that the Russian biological warfare establishment, with its thousands of workers, cannot sim- ply be stopped overnight. There is evidence that Biopreperat scientists have been involved in a genuine search for civilian work in recent years: they boast that inter- leukin, a cancer drug, can be produced by them at a fraction of its cost in Western countries.

Dr Pasechnik also believes simple inertia may be playing a part. Many of those he worked with displayed 'cynicism', saying, 'We are involved in a high-paid job, there is no reason for us to change it.' The secre- cy surrounding Biopreperat meant that it was run inefficiently and would be a poor competitor in the civil market.

The behaviour of many of the concern's executives, however, makes people who meet them receptive to the idea that con- tinued work on germ warfare may possibly be the result of conspiracy rather than cock-up. During a filming visit to Dr Pasechnik's institute in the city now called St Petersburg, in December, I interviewed Yevgeny Sventitsky, his successor as direc- tor.

Mr Sventitsky told me, 'Our institute has never had any direct contact with making biological weapons.' Another scientist 'If they cease to respect you after sex, eat 'em.' working there whispered to me not to believe Mr Sventitsky, and said, 'This man would put black death on the NevskY Prospekt if Moscow told him to.' Dr Pasechnik says Mr Sventitsky used to be in charge of the explosive chamber, where tests were conducted to improve the effi- ciency of bacteria bombs.

During our visit Professor Yevgeny Vinogradov, a deputy director of the insti- tute, was particularly scathing and some- times angry about allegations that they had worked on such weapons. Dr Pasechnik says that Professor Vinogradov was the 'key man' in military research at the insti- tute.

Our visit, complete with the hushed voice of the scientist who wanted us to know what was really going on, felt like an unpleasant flashback to the lying Brezhnev era. The institute's management evidently felt unable to be as frank with us as their foreign ministry has been with the United Nations, even when we told Mr SventitskY that officials in Moscow had confirmed the institute's role in offensive biological war- fare research.

While in Moscow, I made repeated attempts to speak to Yuri Kalinin, the head of Biopreperat. He has declined to meet the press and one can take little comfort from the fact that the man charged with launching this organisation into the brave new commercial world held the rank of general in the Chemical Troops branch of the Soviet Army.

Given the level of Western interest in the St Petersburg institute, it would seem prolY able that there is little military work going on there now. But can the West be sure that small quantities of highly sophisticated germ agents will not elude its inspectors or that General Kalinin might not be tempted to sell his organisation's expertise to SY113, Libya or Iraq? Mr Hogg is frank about the limits of political influence, particularly if President Yeltsin continues to lose real power. Tile Foreign Office Minister told me, 'If y011 have a wholly different r8gime operating.ta Russia . . . which disregarded the policies of President Yeltsin, you do have a vent serious difficulty.' Beyond political pies' sure, Western options with a state suspect' ed of developing biological weapons are, he concedes, 'limited'. The Western desire to see President Yeltsin continue as a strong leader has, greater logic in the field of biological weapons than it does in most areas of Rtla' sian life. Should his conservative allies ever succeed in pushing him out of the WaY' Moscow's hidden germ warfare prograthrn„e will not just be one of the last great secreP of the Cold War, it could easily become focus for hostility and suspicion in a ocr period of international rivalry.

Mark Urban's report on Russia's germ fact°, ries will be broadcast on BBC TV's New night.

Previous page

Previous page