The play's the thing wherein I'll catch the conscience of

. . .

Harry Mount

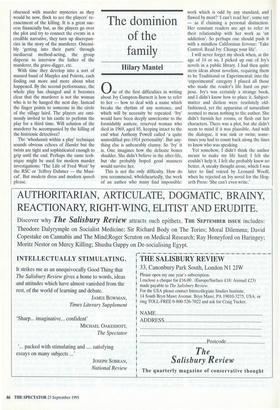

MORALITY PLAY by Barry Unsworth Hamish Hamilton, £14.99, pp. 192

The greatest problem of the novel set in the past is to get the conversation right. Do you attempt perfection, searching around for the actual words used by ancient Greeks or whoever the book concerns? Or do you give up and have them speak like their modern counterparts — Pericles as John Major?

The route most often favoured is the middle one. That is, use today's chat and dress it up with a bit of period vernacular. It works with varying degrees of success: in second world war films, Germans speaking English with a German accent, plus the odd `Achtung' or 'Schnell' have become the pleasant and acceptable norm. Much more difficult are the Middle Ages. In tales set with barons, dirty inns and castles, it seems almost impossible to avoid the cod English favoured by Tony Curtis in epic films of the Fifties — 'Yonda is da castle of my fadda, da dook.' Barry Unsworth was fluent in mid 18th-century English in the Booker Prize-winning Sacred Hunger. Less sure and more Curtis-like is his touch in Morality Play, set in late 14th-century England. The protagonist is described not as having talked but as having 'stood prating',

`bethought' himself rather than just thought and is inclined 'to void [his] bladder'.

This tone grates against the rather clever plot. Nicholas Barber, the narrator, is a cleric fed up with the monotony of tran- scribing obscure verses and Homer transla- tions on behalf of his Bishop. A gang of travelling players adopt him as an actor for their plays. The well-researched world of mediaeval theatre appears somewhat des- perate. 'Owned' by the Earl of Nottingham, the actors are bound by a small stipend to perform for him twice a year. Between these shows, they must eke out a living in these pre-Globe days, going from town to town, putting on improvised works based on biblical episodes. Like a small repertory company up against the National Theatre, they are losing their audiences in droves to the extensive cycle of new plays put on by the guilds. Where Barber's group might perform the story of Adam and Eve for an hour, these guilds fill a week with 20 plays covering the fall of Lucifer to Judgement Day, using the best of special effects: the first trap-doors and stage lights.

Half-starved, the players decide on a crowd-pulling stunt. For the first time, they will act out real events rather than biblical ones. Their leader suggests that 'this is the way plays will be made in the times to come.' There has been a murder in the vil- lage where they are based: a woman has strangled a small boy, apparently to steal the bundle of money he was carrying. The villagers, as bored with religion and obsessed with murder mysteries as they would be now, flock to see the players' re- enactment of the killing. It is a great suc- cess financially but, as the players go over the plot and try to connect the events in a credible narrative, they turn up discrepan- cies in the story of the murderer. Ostensi- bly 'getting into their parts' through mediaeval method-acting, the group disperse to interview the father of the murderer, the grave-digger, etc.

With time they develop into a sort of massed band of Marples and Poirots, each finding out more and more about what happened. By the second performance, the whole play has changed and it becomes clear that the murderer is not the woman who is to be hanged the next day. Instead the finger points to someone in the circle of the village laird. The players are omi- nously invited to his castle to perform the play for a third time. Will solution of the murderer be accompanied by the killing of the histrionic detectives?

The 'whodunnit within a play' technique sounds obvious echoes of Hamlet but the twists are tight and sophisticated enough to grip until the end. Perhaps the same tech- nique might be used for modern murder investigations: 'The Life of Fred West' by the RSC or 'Jeffrey Dahmer — the Musi- cal'. But modern dress and modern speech please.

Previous page

Previous page