Exhibitions

Helen Elwes (Cadogan Contemporary, till 1 May) Luke Elwes: Storyline (Rebecca Hossack, till 15 May)

Cousinly contrast

Giles Auty By chance two young artists who bear the same unusual name are exhibiting in London at present. Both are in their early thirties, are cousins and are members of one of this country's distinguished Catholic families which can claim a record of accomplishment in literature and singing as well as the visual arts. I have known the work of the two of them for a number of years, in Helen's case from the time when she was one of the students at the Royal Academy Schools who benefited especially from the benign influence there of Peter Greenham. Her landscape painting pays a direct tribute to him in its sensitivity and restraint. Her range of work also embraces still-life, mythology, portraiture and re- workings of traditional, sometimes Chris- tian themes such as the Annunciation. Everything is formed by what might be described as an innocent intensity.

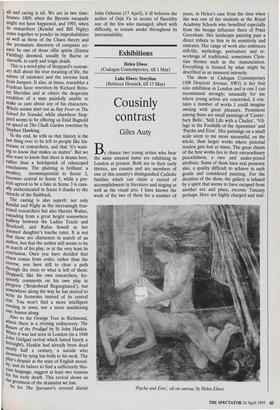

The show at Cadogan Contemporary (108 Draycott Avenue, SW3) is her first solo exhibition in London and is one I can recommend strongly; unusually for me where young artists are concerned, it con- tains a number of works I could imagine owning with great pleasure. Prominent among these are small paintings of 'Canter- bury Bells', 'Still Life with a Chalice', 'Vil- lage in the Foothills of the Apennines' and `Psyche and Eros'. Her paintings on a small scale seem to me more successful, on the whole, than larger works where pictorial tension gets lost at times. The great charm of the best works lies in their extraordinary peacefulness, a rare and under-prized attribute. Some of them have real presence also, a quality difficult to achieve in such gentle and considered painting. For the duration of the show, the gallery is infused by a spirit that seems to have escaped from another era and place, trecento Tuscany perhaps. Here are highly charged and indi- Psyche and Eros', oil on canvas, by Helen Elwes vidual works which make no concessions to fashion and provide living proof that all artists do not have to be subject to the apparent artistic imperatives of the moment.

The works of Luke Elwes at Rebecca Hossack (35 Windmill Street, W1) are very different in nature. He does not seem to want to deal at all with the familiar, from which his cousin creates her very personal poetry. Instead he has turned in his recent subject matter increasingly to desert land- scapes and the people who inhabit them. Clearly he seeks some philosophical truth which he feels cannot be encountered, say, in a Somerset cabbage-patch. His travels have taken him among other places to Western Australia and the Rift Valley and he shows obvious admiration for aboriginal art forms. But direct transcriptions from the natural world are not for him, however miraculous its realms may be. To this extent he is very much a modern artist. He is also influenced especially by the magical poetry found in Miro and Klee. Like the latter, Luke Elwes loves complex surfaces and creates these with considerable deft- ness.

These surfaces are juxtaposed usually with flat colours which symbolise day and night skies in the desert. Painted into and below the surfaces of his deserts we find the archetypal symbols of men who have lived there. Ideas and images such as these are moving — up to a point. Divorced from an objective framework in his art, the artist seems to me to live in a realm of signifi- cances he has encountered himself but can- not necessarily share. For all I know, one may be staring at the secret of life when apparently seeing only some flat, tasteful and very decorative paintings. Attempts to load works of art consciously with too much symbolic meaning can easily prove counter-productive.

There is merit in these works yet some- thing about them makes me uneasy, even beyond the appearance of a quotation from Joseph Beuys in the artist's catalogue. In spite of their superficial beauty, they seem to be signalling their symbolic and intellec- tual pedigrees too obviously. The artist's earlier paintings, featuring strange rock formations in Western Australia, were less polished but more obviously impassioned. In the catalogue essay the artist has written himself, he avers, 'Because man cannot own the desert, he has to see himself sim- ply as part of its pattern.'

This kind of quasi-philosophising is too common and facile; while single men may not wish to own tracts of barren desert, human collectives such as states are only too willing to do so — especially when such tracts contain oil. The artist should concen- trate once more on honing his considerable visual skills and imagination and leave this kind of sermonising to those who generally lack such talents. There are plenty of for- mer art students from Goldsmiths' College to write this sort of thing.

Previous page

Previous page