ARTS

Czech theatre

Memories are not acceptable

Barbara Day describes the Czechs' struggle for artistic independence he stage is a bare traverse in a darkened gymnasium on the outskirts of Prague; an amateur group from Brno is performing Abraham the Patriarch by the 17th-century writer Comenius. Exiled from his native Bohemia, Comenius used the Biblical story as an allegory about his love for his homeland. Eight old-fashioned lan- terns give a shadowed intensity to the actors who, with immobile faces, express themselves through patterns of stylised movement and speech.

Another evening, another part of Pra- gue: in the spendid Vinohrady Theatre an older audience catches breath at a scene in a play by the Georgian author, Chingiz Aymatov. A Soviet officer holds up three incriminating exercise books. 'But those stories were written for his children,' pro- tests the man facing him, 'legends, and his own memories. . ."Unacceptable memor- ies!' exclaims the soldier. 'Memories!' in- sists the other man, 'How can a man's memories be acceptable or unacceptable?' Above the actors, cosmic symbols turn against a cyclorama representing the vast horizon of the Russian steppe. The play, A Day Longer than a Century, is set in a community of Siberian exiles in the 1950s. Its theme is the destruction of memory and the striving of individuals to retain a sense of history.

Theatre for the Czechs is more than entertainment. Since the National Revival of the last century, and even before, it has brought to life that which elsewhere could not be expressed. When, in the early 1970s, a policy of centralisation was im- posed on official outlets for the arts in Czechoslovakia, a performing circuit be- gan to grow up based on clubs belonging to the communist youth union, halls run by the trade unions, and local arts centres. The managers of these have some auton- omy in their programming, and gradually traditions became established; some venues are the home of rock, jazz or pop, others of avant-garde theatre. A flexible and mobile culture developed, program- mes changing nightly as performers juggled their timetables to fit in appearances in Prague as well as in other towns.

In one week this spring I found a teacher from the Conservatoire at three different venues — directing his students in a programme of songs from Czech cabaret, accompanying the 'text-appeals' of the veteran writer and performer Ivan Vysko- cil and appearing in a mixed programme with a professional group. He belongs to the relatively traditional end of the spec- trum; at the other extreme are groups describing themselves as 'post-modernist' with short, crunchy titles like Sklep (Cel- lar), Vpfed (Forward) and Kfee (Spasm). Performances are usually put together from short pieces, poetic, satirical or absurd, often in mime or with unusual vocal effects.

All these are part of the 'second culture' which emerged when, in the nature of things and without any 'dissident' inten- tions, young writers, artists and musicians began to meet and work with like-minded people. Art exhibitions and concerts take place in shops and private houses, orchards and courtyards. The most famous `meeting-ground' was, of course, the Jazz Section, whose attraction for young people so unnerved the authorities that two of its committee members are still in jail.

A few years ago there was optimism that the diversity and flexibility of the fringe groups, with their amateur, semi- professional and free-lance performers, would penetrate and invigorate the profes- sional theatre. But a production like A Day Longer than a Century which combines relevant content with professional artistic skill is difficult to achieve. The Czech name for the established stages is the 'stone theatres', which refers not only to the grandeur of the buildings, but also perhaps to the petrified system of their organisa- tion. Ideas and opinions which flourish on the fringe have little opportunity to mature and be tested before a wider public. Theatre workers in the larger companies are blocked and frustrated by an adminis- tration which uses party membership as a yardstick in employing even artistic staff; outstanding directors, some newly gradu- ated from the Drama Academy and others with years of experience, are refused em- ployment because theatres have to give priority to party members.

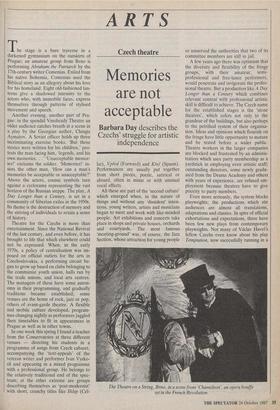

Even more seriously, the system blocks playwrights; the productions which stir audiences are almost all translations, adaptations and classics. In spite of official exhortations and expectations, there have been few new plays from contemporary playwrights. Not many of Vaclav Havel's fellow Czechs even know about his play Temptation, now successfully running in a The Theatre on a String, Brno, in a scene from 'Chameleon', an opera bouffe set in the French Revolution production by the Royal Shakespeare Company. There are memorable produc- tions of Shakespeare, Albee and Jaroslav Hagek, but no repertoire of the kind pursued by Jan Grossman and Otomar Krejea in the 1960s, which inspired a whole generation of playwrights.

In the expectant atmosphere which pre- ceded Gorbachev's spring visit to Prague, a group of theatre workers succeeded in publishing a manifesto in the theatre news- paper Scena (30 March 1987). It was a call for artistic independence and freedom from bureaucracy: . . . Most energy is taken up with trying to secure things which ought to be a matter of

course if you are involved in creative work . . . instead of a naturally operating theatre we have an economically demanding self- devouring administrative machine apparent- ly capable of functioning even without any artistic company and moreover led by people from outside the theatre with no understand- ing of stage practice and who certainly do not understand the creative side.

The language is mild compared with the British theatre's attacks on Arts Council policy and government funding, but similar manifestos from writers, artists and musi- cians failed to find a publisher at all. The 25 signatories — professional directors, performers and playwrights — claim that the contemporary established theatre is run with both eyes on directives coming from above and mediated through bureaucrats who themselves will neither take nor give responsibility. The system based on the unpopular Theatre Law of 1978 is perceived as being antagonistic to creative work. One provision of this law lays down the exacting conditions under which a new theatre group can originate, or an exhausted one close down. Another consequence of the law was to put existing studio groups under the parentage of an established stage. The survival of these groups no longer depends on the produc- tion of original and exciting work, but on their adaptability to the requirements of their 'parent'. The daily struggle with these requirements becomes the first priority.

Numbers of contemporary, socially relevant plays . . . and productions have become victims of adminstrative intervention. In a similar way many names have disappeared from Czech theatrical life, and for a number of years we have been pretending that these people and their works never existed.

The manifesto was published in anticipa- tion of the May conference of the Union of Czech Theatre Artists, which turned into a battle of wills bringing no victories. Of the signatories to the Scena article, two were elected to the theatre section and one of those will serve on the general committee. One signatory was elected to the Union of Slovak Theatre Artists. Little opportunity was given for the new members to speak. No final document was produced, but in spite of pressure from the younger theatre workers the union has blocked requests for the conference to be reconvened. The signatories to the Scena article have there- fore organised two conferences them- selves, one to be held in Brno in mid- December, another in the spring. These will formulate questions to be publicly addres- sed to the Ministry of Culture, the Theatre Institute and local councils dealing with the running of theatres.

The closing moments of the May confer- ence belonged to the veteran artist Milog Kopeck from the Vinohrady Theatre. I'm no politician, he said, but an actor, a clown; and the precondition of a clown's worth is to understand the moral condition of his country.

Previous page

Previous page