Middle East Notebook

By IAN GILMOUR BRITAIN became involved in the Middle East to safeguard her communications with India. But when in 1947 she gave India her independence she retained the communications; and in the ten succeeding years she suffered her two greatest humiliations since the war—and, with the excep- tion of Munich, of this century—Palestine and Suez. The question any visitor' to the Middle East is bound to ask himself is : Are we going to suffer a third?

The fact that our interest in the Middle East was originally secondary or indirect meant that we rarely ruled directly. We dominated but did not rule—a system which combines all the dis- advantages of colonialism with few of the advan- tages. Inevitably, therefore, there is much more dislike of Britain than is found in our ex-colonies, though the dislike is sometimes tinged with respect and is now tempered by dislike of others, in par- ticular the Americans. Some of the dislike and some of the respect is due to the delusion that we are much more active and powerful in the area than in fact we are. Indeed, anyone who spends his time worrying whether or not Britain can still be considered a Great Power will be pleasantly reassured by a visit to the Middle East. In Iran he will be told that the Shah's regime would not last a moment without British support and that the British Ambassador changes the Prime Minister when he gets bored with the same old faces; in Kuwait, that Britain is pushing Kuwait into union with Iraq; in Iraq, that Britain is preventing Kuwait from joining her. He will also, of course, be told that the Hashemites and Nuri Pasha are British stooges and that the effec- tive centre of Iraqi politics is the British Embassy. Even in the Lebanon he will find, possibly to his surprise, that we are the dominating factor. (`After all the millions of dollars the Americans have spent here,' an opposition leader told me in Beirut, 'they have only one politician, you have all the rest of the Government. They are all your proteges, and a lot of gangsters they are.') Only in Egypt—but the Great-Power-minded visitor would find Egypt altogether too painful.

Even Arabs most convinced of this, however, find it difficult to explain exactly what we are try- ing to do with our power, and those who are not find it no easier. Certainly British policy, so far as it can be discovered, looks rather lop-sided. An Egyptian Minister defined it to me as being `to hold the Gulf, and to do that you have to hold Iraq.' But he was giving too great a precision and 'Coherence to what is less a policy than a variety of vague aspirations—amongst them to keep the Russians out, stand no nonsense from Nasser and settle the Arab-Israeli problem. In attempting to keep the Russians out we are behaving like those astute detectives who, when they have their quarry covered, refuse to be taken in by signs that they are about to be hit on the head by an accomplice behind them. Only in our case there is somebody behind us. While the Baghdad Pact resolutely faces Russia to the north, the Russians have gone round behind and are facing it from the south. Moreover, while opposing the Russians we do not have diplomatic relations with two of the three biggest units in the area— the United Arab Republic and Saudi Arabia. Our attitude to Colonel Nasser and Egypt is particu- larly odd. Less than two years ago Colonel Nasser was being denounced as a menace to this country's vital interests, and Egypt was described by Mr. John Connell in a book defending the Suez operation as The Most Important Country. What are we doing about Colonel Nasser and The Most Important Country today? Taking every opportunity to denounce him in the press and from time to time holding talks on financial Problems at civil-service level in Rome.

The Government is not alone in trying to ignore or despise Nasser. Two books on the Middle East were published in February, one by a Conserva- tive, one by a Socialist. The Conservative, Mr. Anthony Nutting, confidently told his readers: `Nasser . . . is a conspirator, not a statesman. In this role he has offended and estranged his friends and braced and forewarned his enemies. This plus his flirtation with Moscow is losing him the campaign to subject the Arab world to his domination. . . . Provided the West do not ruin everything by attacking or arresting him, he will in due course meet a conspirator's fate.' The Socialist, Mr. Paul Johnson, was equally sanguine. Britain was to become 'the patron of Arab nationalism.' We would apparently discharge the duties of this rather obscure office by educating Arab Socialists at a summer school in Britain and by breaking the Arab blockade of Israel—an activity on the face of it more becoming to the patron of Jewish than of Arab nationalism. But be that as it may, Mr. Johnson managed to write his chapter describing in some detail Britain's 'new role' in the Middle East without once mentioning Nasser.

THE SHEIKHDOMS

Whatever else we do about ttie Persian Gulf we do not ignore it. Every schoolboy now knows or soon will that over half the oil used in this country is Kuwaiti oil, and everybody has read how in a few short years the Sheikhdom has moved from camels to Cadillacs. Much has been made of the fantastic extravagance and opulence of Kuwait, and the most lurid colours have been used to describe the place. Undoubtedly it has bizarre elements. Its technial school owned with eight students and twenty-two teachers. But with oil revenues of £100 million and a population of only 200,000 it has surely been right not to emulate the budgetary strictness of Mr. Paul Getty. In such circumstances extravagance is seemly. There has, too, been some inefficiency, but it really does not matter very much—it may even be a good thing if it helps to spread the wealth. Kuwaitis now run practically everything themselves and on the whole they manage very well. Politically there is the usual yearning for Arab unity combined with the (justifiable) suspi- cion that all outsiders are after their money.

Kuwait has no recognisable form of govern- ment, a situation which those who have been educated in the West and used to classifying countries as monarchies or republics, colonies or independent States, dictatorships or democracies, etc., find degrading if not intolerable. Even the wrong sort of government would be preferable, they think, to no sort of government. Kuwait is in fact an independent State with British protec- tion; it is quite independent internally; and externally although Britain conducts the foreign policy of the Sheikhdom, she conducts it in, as it were, a civil-service capacity. The policy is the Ruler's; we carry it out. There are, not surpris- ingly, no democratic institutions, and there is no system of law other than Sheikhly justice, which is haphazard and inevitably unpopular.

Political activity is largely 'confined to the clubs. There, in considerable luxury provided by the Government, clubmen can reform the world and Kuwait to their hearts' content. They are not noticeably grateful for the facilities provided; but no doubt gratitude was not expected. By canalis- ing political activity into the clubs the Govern- ment ensures that the politically discontented speak only to the converted. I spent an evening at one of them, and on Turkish coffee—alcohol is forbidden in Kuwait except in exclusively non- Kuwaiti circles—I did my best to answer com- plaints against Britain, America, Iraq, Israel, Jordan and almost everything else that has hap- pened in the last forty years. The only man in no need of defence was Colonel Nasser.

The Sheikdoms of Bahrein and Qatar are in a similar relationship to us, though they are in differing stages of development from Kuwait and have much less oil. We have Political Agents in each of them and a Political Resident for the whole Gulf, who lives in Bahrein.

Obviously this set-up does not look very per- manent, and a number of suggestions have been made. Mr. Nutting thinks that there should be a Five-Power guarantee by Britain, America, Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia of the status quo in the Gulf. But as Iraq wants Kuwait, Iran wants Bahrein and Saudi Arabia would like practically everything, this might be rather difficult to secure. It has also been suggested that we should tell the Sheikhs that in a few years' time we shall have pulled out completely except for guaranteeing their independence, but that is substantially the present position and we should in the popular mind be just as closely identified with the regimes as ever we were. A third possibility is that Kuwait, Bahrein and Qatar should be formed into a federation. But there is no reason to believe that either the rulers or the peoples of the Sheikhdoms want to be federated, and no particular reason to believe that such a federatioh would work. Joined together they would be scarcely less vulnerable than they are singly; in- deed, a federation would look so appetising to outsiders that they might be more so.

What we could do, it seems to me, is to abolish the titles of Political Resident and Political Agent. Apparently the words do not sound so bad in Arabic, but to have Ambassadors and Ministers instead of these relics of the Indian Empire would make our position look more normal, though logi- cally if we had an Ambassador other countries should have one too. But logic could be dis- regarded; and there will anyway probably come a time when other countries will have representa- tives in the Sheikhdoms whatever name we give to ours.

Such a change would be only a small step, and in general our policy of holding on and hoping for the best seems the right one. It is not tidy or spectacular and it is unlikely to last for long. But there are few places in the world where it is possible to have a long-term policy; and it is not what we do or leave undone there, but what happens elsewhere in the Middle East that will determine what happens in the Gulf. The future of the Sheikhdoms cannot be considered in isolation from the rest of the area any more than the future of India in 1947 could have been settled by agreement with the Indian Princes.

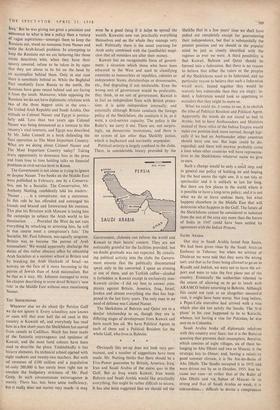

SAUDI ARABIA

Our stay in Saudi Arabia lasted four hours. We had been given visas by the Saudi Arabian Embassy in Teheran; but when we arrived at Dhahran we were told that they were the wrong sort; and that so far from being allowed to go on to Riyadh and Jeddah, we were not to leave the air- port and were to take the first plane out of the country. Eventually the authorities relented to the extent of allowing us to go to lunch with ARAMCO before returning to Bahrein. Although this could not rank as an altogether successful visit, it might have been worse. Not long before, a Pepsi-Cola executive had arrived with a visa which also did not satisfy the Saudis. The 'first plane' in his case happened to be to Karachi, whence, not having a visa for Pakistan, he was sent on to Colombo.

Saudi Arabia broke off diplomatic relations with this country over Suez; but it is the Buraimi questiop that prevents their resumption. Buraimi, which consists of eight villages, six of them be- longing to Abu Dhabi and two to Muscat, is the strategic key to Oman; and, having a relatively good summer climate, it is the Aix-les-Bains of Abu Dhabi. The Saudis occupied it in 1952 and were driven out by us in October, 1955. Just be- cause our case—or rather that of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi and the Sultan of Muscat—is so strong and that of Saudi Arabia so weak, it is extraordinat,,, difficult to devise a compromise which would be fair to Abu Dhabi and Muscat and which would save the faces of the Saudis. Nevertheless, to do so should not be beyond the wit of man, particularly as there is no oil there.

Last weekend the Emir Feisal indicated that the Saudis would accept arbitration. Possibly the Sheikhs of Kuwait, Bahrein and Qatar might act as mediators, though they would probably be reluctant to be put in a position whereby they might have to offend Saudi Arabia. A neutral zone is more than the Saudis deserve, but it may be the eventual solution.

ABU DHABI I was described in the Teheran Times as 'Mr. Iran Kilmore' and ,in the Abadan News slightly less lethally as 'the grandson of newspaper pro- prietor Lord Beaverbrook,' which was, I suppose, meant to be a compliment. The relationship pre- ceded me down the Persian Gulf and, for some reason which I did not understand, it was easier to tell the Ruler of Abu Dhabi, who was looking forward to a discussion on the iniquities of the. Express, that this would be profitless—as grand- father and grandson did not get on—than to tell him we were not relations. Throughout our stay he referred to me as 'Brook.'

Abu Dhabi is still in the pre-petrol phase of Arab life. For many years various companies have been searching for oil' on the mainland, but they have found nothing. It looks, however, as if the Ruler's patience will be rewarded by better luck in the sea. The demesne of Abu Dhabi includes Das Island in the Gulf, and using Das as a base a company, two-thirds owned by BP and one- third by the French, is drilling in the sea by means of a monstrous contraption which stands on stilts on the sea bed. The drillers spend half their time on the barge and half on Das recuperating. When I landed there by helicopter, nothing had been found. But since then some traces of oil (the first to be found in the Gulf) have been discovered, but it is not yet known if it is there in commer- cial quantities. If it is not, the barge will pull up its legs and try elsewhere.

IRAQ Iraq's progress has been vast. She genuinely spends 70 per cent. of her considerable oil revenue on developing the country, and her ably run De- velopment Board has some staggering achieve- ments to its credit. To build the Wadi Tharthar barrage and ditch near Samarra it was necessary to move half as much earth as had to be moved for the construction of the entire Suez Canal. The barrage with the golden dome of Samarra in the background makes a fine sight from the air; at least we were told it does. When we flew over it they had taken it into their heads to peel the gold off the dome, leaving what looked like a mud hut.

Both the Tigris and the Euphrates have been tamed and Baghdad freed from the danger of flooding. Irrigation has reclaimed enormous areas of previously arid land, though since irriga- tion in Mesopotamia produces salination unless it is checked by adequate drainage there is a danger that it will all go out of use again, and some of it has already been lost. But then econo- mic triumphs have brought the regime no political dividends, and it is doubtful if they will do so even when the benefits from them have seeped much wider and farther down than they have already done. Not that Iraq is badly governed. Cairo Radio wildly exaggerates the number of political prisoners. Iraqis leaving Cairo are in the habit of making moving farewell speeches to the effect that for what they have said and done in Cairo they are bound to be thrown into a dungeon. But to their relief or disappointment their arrival in Baghdad is less dramatic : they merely go home.

,The regime has been unnecessarily harsh with political parties and the press. Iraq treats news- papers like other countries treat night clubs : one has been closed forty-five times in thirty years. And the censorship, like all censorships, is some- times foolish.

But all in all Iraq is an unusually benevolent and highly competent police State, and its rulers may well feel the injustice that their efforts are so ill-rewarded with popularity. For ill-rewarded they certainly are. It is not easy to find a sup- porter of the Government who is not a member of it. Partly, this is due to a hangover from the Otto- man Empire and the British Mandate. Govern- ments are still regarded as engines of foreign domination. But the primary reason is Arab nationalism. As elsewhere nationalism is identified with Nasser. Estimates of the extent of pro-Nasser feeling in the country obviously cannot be at all exact, but even people who deplored everything to do with Egypt did not put it below 80 per cent.

In these circumstances one cannot help think- ing it unwise of Iraq to have a head-on clash with Egypt. Iraq did not congratulate Nasser on the formation of the United Arab Republic. And when Nasser congratulated Iraq in quite warm terms on the formation of the Federation with Jordan, her reply was cold and late. This was extraordinarily inept. It is compulsory orthodox)! for Arabs to welcome any diminution in the number of Arab States, and the resulting war of words between Cairo and Baghdad was regarded by Iraqis as being caused by their Government.

Baghdad Radio has recently been making much of the idea or fact that Egyptians are not Arabs. It may have drawn some blood on this point (particularly as some of Cairo Radio's lies have been even wilder than usual and of the sort that can be seen to be untrue, e.g. imaginary riots in Baghdad): but it will not have much effect. Cairo is the centre of the Arab world culturally and politically, and Baghdad is not going to replace it any more than Manchester, with all its virtues, could seriously compete with London.

EGYPT Cairo is not looking its best just now. In order to demonstrate to the Syrians that they were as excited as they were at the formation of the United Arab Republic, the Egyptians have built a series of stage triumphal arches at the main road junctions. Unfortunately, the Revolutionarl Council's aesthetic sense is less highly developed than its political, and it would be hard to imagin° a more regrettable amalgamation of the tawdrY and the garish, the vulgar and the gimcrack. Happily, some of them were blown down 0/' the wind, but, refusing to learn, the Egyptians built them up again. Because of a new rent lavi the Cairo building boom is at an end, but while it lasted it produced some good skyscrapers" though there are ugly rumours that the biggest one, which is next door to the Italian Embassy is about to fall on top of it.

The English have been virtually absent only since Suez, but the Egyptians' idea of us seems to have been frozen into a mould made in about 1922. People were shocked and incredulous when in an unguarded moment I admitted that I did not play polo. (It is still played regularly and skilfully at the Gezira Club.) But absence has certainly made the Egyptians' hearts grow fonder and Cairo is a pleasant place for the English to visit at the moment. It is true that they may occasionally be embarrassed by tactless remints' cences about bombs—but embarrassment is some' how greatly diminished by the Egyptian tendenol to pronounce the second 'b' in bomb.

Officially Anglo-Egyptian relations are coo' fined to spasmodic financial talks in Rome, Our attitude to them is understandable, bUt it has not been sensible. Nor, indeed, has that of the Egyptians. They have been extraordinarily dilatory, and after agreeing to leave out of the talks inter-governmental claims they changed their mind and now say that a settlement of their war-damage claims is essential to an agreement. Nevertheless, it seems that this change of mind was provoked by our putting into a draft agreement a disclaimer of liability' a foolish and unnecessary thing to do; and it also seems that on the question of neutral arbitration on the value of British property which has been nationalised by Egypt the Egyptians hale made more concessions than we have.

If the Egyptians give way again and agree that their bomb-damage claims should be set 00 against the Canal Base—at the moment they are claiming that the former amounts to about £25 Million more than the value of the latter—we may get an agreement, but it will be worth much less than it need have been. It is here that the Govern- ment's basic hypocrisy over Suez has been damaging. Very few erstwhile Suez men will now m private defend the operation (the farthest they will go is to say, 'Whatever the rights and wrongs of Suez . . .'). But they do not dare to admit it in public, and such an admission would do untold good to Anglo-Egyptian relations. The Egyptians still have a feeling that we do not regard them as equals, that we regard them as people it is all right to beat up every now and then. And our refusaj to admit what we know and they know perfectly well—that we were utterly in the wrong —lends force to that feeling. For the Minister of State at the Foreign Office to get up in the House of Commons and say that we do not recognise any liability for the damage done by our bomb- ing and invasion may be a shrewd piece of finan- cial hard bargaining, but bombs and bullets are a harder currency than the pound sterling, and if we want to have good relations with Egypt and not merely to save ourselves a few million pounds, a generous gesture, not undignified haggling, is the proper course.

Perhaps, however, the Government does not want good relations with Egypt? What, after all, are we trying to do to Colonel Nasser? Dis- place him? Drive him ever farther into the arms of the Russians? Send him to Coventry for having been bombed? The Government has stood Clausewitz's maxim that war is an extension of diplomacy by other means on its head to read 'diplomacy is an extension of war by other means.' What it has not noticed is that we lost the war. To try economic pressure and then mili- tary pressure is a sensible enough procedure, but to invert the sequence is less effective.

Possibly at the back of the Government's mind is the pious hope that economic pressure will topple Nasser. In an area where the normal mode of political action is conspiracy and plot, any- thing can happen, but Nasser seems less likely to fall from power than any other political leader in the Middle East, Not that the economic pres- sure has been without effect. There is a serious shortage of consumer goods which hurts the only people in Egypt who have political importance. There has already been trouble at Alexandria over cotton sales to Eastern Europe, and there are signs of a return of corruption. Classical Egyptian corruption was over land, and because the new corruption has nothing to do with land it has not been noticed. But the civil service did not get the rise it was promised to match the rise given to the army at the time of Suez, and shortage of money and shortage of goods have dimmed the idealism of the first years of the revolution. Minor bureaucratic corruption which was un- known a year or two ago has begun. It is on a small scale, but it is there. However, corruption in Egypt is of doubtful advantage to this country, and so far from bringing Nasser down or making him more amenable our economic pressure merely drives him to further external excesses.

It can be argued, and no doubt would be by the Government, that to come to any terms with Nasser which were not an extremely hard bargain would be construed throughout the Middle East as a blow to our prestige and a kick in the stomach to our present friends in the area. Un- fortunately, our prestige has already suffered; nobody in the Middle East regards Suez as any.. thing but a disastrous failure, and for us to admit it would not make the failure any more obvious than it is already. It is no good trying to save a face you have already lost.

Nor would a rapprochement with Nasser harm our friends. Indeed, it would considerably help them. Our only friends in the area, to all practical purposes,, are the regime in Iraq and Jordan and the Rulers of the Persian Gulf. Plainly the Sheikhs of the Gulf would lose nothing by improved Anglo-Egyptian relations. What of the Govern- ment of Iraq and Jordan? The rulers of Iraq are the oldest and best friends of the West in the Middle East and there can be no question of our letting them down. But even less than us are they helped by our present identification with them. So long as they are regarded as British stooges, their chances of coming out on top in their struggle with. Egypt are negligible.

Neither Iraq's cold war with Egypt nor Britain's identification with Iraq, then, is to the advantage of either Iraq or Britain. That is not so much to say that we should back both horses in the Arab race—that we should imitate that prudent racehorse-owner in Iraq who has called one of his horses Nasser-Nuri —as that we should back neither horse. Certainly if we go on as we are we are liable to find ourselves with a numb?.r of Chiang Kai-sheks on our hands and no Formosa.

(To he concluded)

Previous page

Previous page