ARTS

Crafts

An appetite for beauty

Tanya Harrod

Walter Crane: Artist, Designer and Socialist (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, till 27 March) The Holy Grail Tapestries and Pre- Raphaelite Drawings (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, till 2 and 30 April

Artists' Jewellery (Wartski Ltd, 8-12 March)

There are some exceptional exhibitions outside London this month. The finest, at Manchester, is the first comprehensive survey of the work of Walter Crane. Crane is perhaps best known for his Toy Books created in collaboration with the engraver and printer Edmund Evans. His early illustrations for the radical wood-engraver W. J. Linton are accomplished hack-work but by the late 1860s Crane had developed his unique style. His discovery of Blake and his acquisition of a set of Japanese prints led him to simplify: masterpieces like The Fairy Ship and Aladdin are a wonderful combination of outline, flat areas of colour and dramatic viewpoints. In others, like The Beauty and the Beast, Crane drew on his extensive knowledge of the applied arts to create interiors of claustrophobic, eclectic richness. Proving that parents buy children books for their own pleasure, the Toy Books brought Crane work as an interior designer and led on to his extraordinary range of designs for wallpapers, textiles and ceramics. By the 1880s the Toy Books had found unex- pected admirers — Huysmans praised them in a Salon of 1881 and they became something of a cult amongst symbolist painters in Belgium. Poor Crane! He rather resented the popularity of his chil- dren's books and certainly hated his sobri- quet `the Academician of the Nursery'.

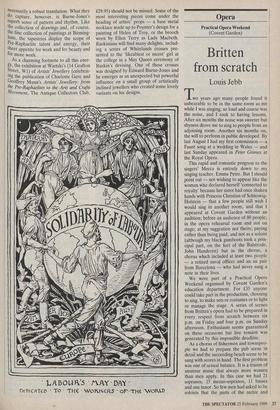

Crane had a modest talent as a painter. At the Whitworth there are some charming landscapes and a couple of rather mawkish allegorical works. In time he came to believe that applied art, or `constructive art' as he called it, was superior to easel painting — mere `portable, often specula- tive, property'. As an old man he was greatly excited by the first Post- Impressionist exhibition organised by Ro- ger Fry. Somewhat surprisingly he evident- ly saw Gauguin and Denis as possible recruits to the Arts and Crafts cause, suggesting that with their strong sense of pattern they would best develop their talents by turning to weaving, mosaic and pottery. Crane looked forward to the day when all art would be public art, when machinery would do the heavy work, freeing the working classes to form guilds that would stage picturesque May Day festivals. Some of Crane's best designs were made in anticipation of this arcadiaa society — trades union banners, the covers, of innumerable socialist magazines, his, famous Cartoons for a Cause. He invented a persuasive image of the worker — a hobnail-booted figure of Raphaelesq0e beauty — that provided an idealised identr ty for the Labour movement long after his death.

Though hardly an establishment figure, Crane was a great organiser and joiner, a founder member and first chairman of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society and a member of the Art Workers Guild. Nowa- days it seems customary to mock the romantic socialism of Morris, Ashbee and Crane and point out that most of their work was commissioned by the very rich, and that, even worse, they were not badlY off themselves, kept servants etc, etc. But Crane in particular had sound views about the social function of art which still hold good today. His little book of essays, The Claims of Decorative Art, should be read by all artists and designers. At Birmingham Museum seven of the Holy Grail tapestries designed by Edward Burne-Jones for William Morris's Merton Abbey workshops are on display for the first time in many years, together with the museum's magnificent collection of Pre- Raphaelite drawings. At Merton Abbey the weavers worked from photographic enlargements of Burne-Jones's designs and Dearle, Morris's master weaver, added borders and flowers with mediaeval aban- don. But for all his skills Dearle was defeated by some of the special beauties of Burne-Jones's art. Burne-Jones was a mar- vellous colourist, who bathed his scenes of remote beauty, love and death in an unearthly silvery light. The tapestries arc necessarily a robust translation. What they do capture, however, is Burne-Jones's superb sense of pattern and rhythm. Like the collection of drawings and, of course, the fine collection of paintings at Birming- ham, the tapestries display the scope of Pre-Raphaelite talent and energy, their sheer appetite for work and for beauty and for more work.

As a charming footnote to all this ener- gy, the exhibition at Wartski's (14 Grafton Street, W1) of Artists' Jewellery (celebrat- ing the publication of Charlotte Gere and Geoffrey Munn's Artists' Jewellery: from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement, The Antique Collectors Club, £29.95) should not be missed. Some of the most interesting pieces come under the heading of artists' props — a base metal necklace made up to Poynter's design for a painting of Helen of Troy, or the brooch worn by Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth. Ruskinians will find many delights, includ- ing a series of Whitelands crosses pre- sented to the likeablest or nicest' girl at the college in a May Queen ceremony of Ruskin's devising. One of these crosses was designed by Edward Burne-Jones and he emerges as an unexpected but powerful influence on a small group of artistically inclined jewellers who created some lovely variants on his designs.

' LABOUR:5 PlAY • DAY •

r) OICATED ' To ' THE WoKKERS of THE 'WORLD

Previous page

Previous page