Museums

Centre for Contemporary Art Luigi Pecci (Prato)

Italy goes contemporary

Alistair Hicks

The city of culture is fast becoming a restorer's paradise. The legacy of Flor- ence's flood of 1966 is a permanent army of occupation made up of a new breed of 'artist' whose main task is to keep him or herself in a job at whatever price. These latter-day servants of Savonarola plan to keep Masaccio's Brancacci Chapel to themselves in perpetuity, they have the luxuriant Gozzoli 'Procession of the Three Magi' at their mercy and seem to have developed an insatiable appetite for Last Suppers. But the most controversial siege is taking place in the Piazza della Signoria, which has been turned into a building site while it is debated whether the Renaissance city really needs a Renaissance square at its centre. Wouldn't it be nobler, the cry goes up, to have second-rate Roman ruins

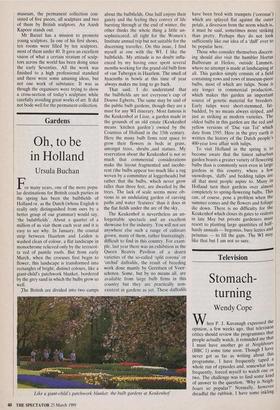

Marini's `Piccola Pomona', 1944 under perspex instead of dull grey flag- stones?

Those here who believe that art im- proves with age have had one defeat lately. They may have leapt with joy when Sandro Chia, a famous if out-of-favour son of the city, had his exhibition `suppressed', they may have managed to ensure that the new contemporary museum was built in neigh- bouring Prato rather than in the Tuscan capital itself, but they have seen San Pancrazia, complete with Alberti's amend- ments to the facade, turned into a museum dedicated to the sculptor from Pistoa, Marino Marini.

The museum is best visited during day- light hours when the white-washed basilica rejoices in its new-found natural light. From the piazza the sight of Marini's `Horse 1939' perched up behind Alberti's Roman temple column facade encourages the visitor. The insertion of three modern floors and a labyrinth of connecting stairs and corridors looks as though it has been completed with the minimum of fuss, but under artificial light great red iron girders loom from the ceilings and there seems to be an alarming number of pointless dead ends. The architects did have to work, however, with the daunting knowledge that the great architectural jewel of the Renaissance, Alberti's Rucellai Sepolcro, is locked away (only to be seen once a week during Saturday evening Mass) in the one remaining used part of the church.

Since the artist's death at 79 in 1980, his widow, Marina Marini, has fought to see the museum finally open last autumn. She has augmented his donation, so that a good idea of his work can be had at one visit. The paintings, with a few exceptions from the beginning and end of his life, reassure us that he took the right decision in turning to sculpture. After feasting oneself on the Renaissance treasures in Florence, it is refreshing to come across blasts of Etrus- can, Cycladic and T'ang influence in clear- ly modern work. Waves of ancient influ- ences are perhaps best assimilated in Mari- ni's 'Pomonas', the goddess of the fruit trees, and horses with and without riders. Some of man's oldest relationships, those with horses and nature, are explored. Full forms overflow with primitive feeling re- tuned to the present day.

Though its holdings in art far outshine those of most cities of the world, Prato is considered by most Florentines to be a cultural backwater, so they were belatedly irritated by its achievement in setting up the first contemporary art museum in Italy. Initiated by a gift of the building on the industrial outskirts of the city by the Pecci family in memory of a lost son, the gallery has set itself some ambitious tasks. The director, Amnon Barzel, has made a ten- year rule, allowing himself only to buy works of art made within the last decade. He wants to build a collection that over the years acts as a broad catalogue for their exhibition schedule. When I visited the museum, the permanent collection con- sisted of five pieces, all sculpture and two of them by British sculptors. An Anish Kapoor stands out.

Mr Barzel has a mission to promote young sculptors. In one of his first shows, ten rooms were filled by ten sculptors, most of them under 40. It gave an excellent vision of what a certain stratum of sculp- tors across the world has been doing since the early Seventies. All the work was finished to a high professional standard and there were some amusing ideas, but not one work of substance. It was as though the organisers were trying to show a cross-section of today's sculpture while carefully avoiding great works of art. It did not bode well for the permanent collection.

Previous page

Previous page