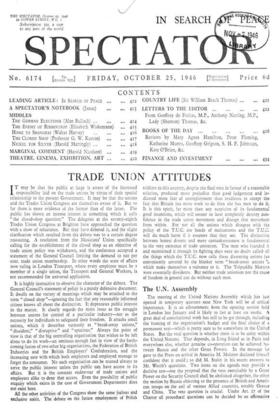

TRADE UNION ATTITUDES

It is highly instructive to observe the character of the debate. The General Council's statement of policy is a purely defensive document. It dwells on the variety of meanings which may be attached to the term " closed shop "—ignoring the fact that any reasonably informed citizen knows all about the distinction. It deprecates public interest in the matter. It clearly regards the main issue as the struggle between unions for control of a particular industry—not as the necessity for individuals to safeguard their freedom. It attacks small unions, which it describes variously as " break-away unions," " dissident," " disruptive" and " spurious." Always the point of view is that of the big controlling organisation that wishes to be left alone to do its work—an ominous enough fact in view of the forth- coming fusion of two other big organisations, the Federation of British Industries and the British Employers' Confederation, and the increasing ease with which both employers and employed manage to forget the consumer. No such organisation can be trusted always to serve the public interest unless the public can have access to its affairs. But it is the constant endeavour of trade unions and employers alike to deny that access. Even the possibility of public enquiry which exists in the case of Government Departments does not exist here.

All the other activities of the Congress show the same jealous and exclusive spirit. The debate on the future employment of Polish soldiers in this country, despite the final vote in favour of a reasonable solution, produced more prejudice than good judgement and in- dicated more fear of unemployment than readiness to accept the fact that Britain has more work to do than she has men to do it. It is this spirit, far more than any suspicion of its fundamental good intentions, which will sooner or later completely destroy con- fidence in the trade union movement and disrupt that movement from within. For not all the unions which disagree with the policy of the T.U.C. are bands of malcontents and the T.U.C. will do. much harm if it assumes that they are. The distinction between honest dissent and mere cantankerousness is fundamental to the very existence of trade unionism. The men who founded it and maintained it through its fighting days were no doubt called all the things which the T.U.C. now calls these dissenting unions (so conveniently covered by the blanket term " break-away unions '), which make themselves a nuisance to it. The Tolpuddle Martyrs were essentially dissidents. But neither trade unionism nor the cause of freedom in general can do without such men.