Townies

Simon Jenkins

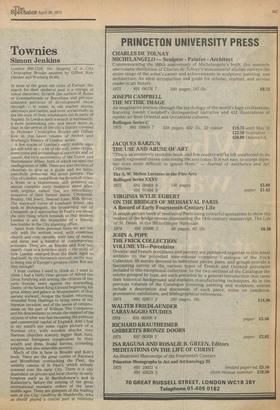

London 800-1216: the Shaping of a City Christopher Brooke assisted by Gillian Keir (Seeker and Warburg £8.00)

In most of the great old cities of Europe, the search for their medieval past is a voyage of visual discovery. Scratch the surface of Rome or Constantinople or Barcelona and pre-renaissance patterns of development show through — in ruins, in old market places, alleyways and castles, and even occasionally in the life-style of their inhabitants (as in parts of Naples). In London such a search is necessarily a more painstaking one, and never more so than in the period of the city's history covered by Professor Christopher Brooke and Gillian Keir in this latest volume of Secker and Warburg's 'History of London' series. A few traces of London's early middle ages are still with us — a bit of old wall, some crypts, some coins and archaeological survivals and, of course, the twin monuments of the Tower and Westminster Abbey, both of which escaped the conflagration of 1666. There are also the sites of churches to give us a guide and we have, mercifully preserved, the street pattern. The City of London, saved from the dictats of either a Wren or a Haussmann, still presents an almost complete early medieval street plan, with original names that are remarkably evocative of their former status: Cheapside, Poultry, Old Jewry, Seacoal Lane, Milk Street. The wayward curve of Lombard Street, the kink in Bishopsgate, the broadening out of Cheapside as it approaches St Paul's are about the only thing which reminds us that modern London is not the brainchild of a lunatic box-builder in the City planning office.

Apart from these precious links we are left only with the written word, with countless church and civic records, with lists of names and dates and a handful of contemporary accounts. They are, as Brooke and Keir say, merely clues to a detective story — the story of how London emerged from the Dark Ages to find itself, by the thirteenth century, on the way to being one of Europe's greatest cities. But are they enough? I must confess I used to think so. 1 used to think I had a fairly clear picture of Alfred the Great fortifying and arming the citizens of the early frontier town against the marauding Danes; of the Saxon King Edward beginning his great Abbey and palace at Westminster; of that ancient stalwart, Ansgar the Staller, returning wounded from Hastings to bring news of the Norman invasion; and of the series of compromises on the part of William The Conqueror and his descendants to retain the support of the citizens of what was fast becoming the political and commercial capital of England. And I had in my mind's eye some vague picture of a Norman city, with wooden shacks, tiny Norman churches scarcely bigger than huts, occasional foreigners conspicuous by their wealth and dress, feudal barons, crusading knights, and also miserable poverty. Much of this is here in Brooke and Keir's book. There are the great castles of Baynard and Montfichet overlooking the Fleet, the wealthy canons of St Paul's, which already towered over the early City. There is a city dependent on private and local charity in early hospices such as St Bartholomew's and St Katherine's, before the coming of the great international monastic orders of the later middle ages. There are glimpses of the leading men of the City: Geoffrey de Mandeville, who as sheriff played a crucial part in relations between City and Crown, and Henry FitzAilwin who emerged from the battle for "commune" status in the 1190s to become London's first mayor. There are the marvellous names Tofi the Proud, Menasses the Scribe, Aylwin Fink the Moneyer, and Gilbert the Universal. And there is the shambles of local government as the Danish, Saxon and Norman traditions fought it out in hagas, sokes, wards, reeves stallers and gemotes to produce a structure which still largely survives today. Indeed it was not until 1907 that the 126 separate parish authorities established by the end of the twelfth century were partially reformed. Not surprisingly, the City was omitted by exasperated Domesday surveyors.

But these are simply the bare bones, 'the skeleton of a city. For all its wealth of detail and scholarship (a staggering seventy-five names in the acknowledgements and twenty-four pages of bibliography), this volume adds little by way of flesh. Although it opens with an excellent effort at comparing medieval London with similar-sized Italian and Spanish towns today, it tails off into what at times seems like a mass of lecture notes. The authors appear lost in their material, wandering off into asides and continually, infuriatingly, protesting their and our ignorance.

The one great chronicler of this period William FitzStephen, biographer of Thomas a Becket pops up every now and then to give us a welcome glimpse of daily life in Norman London, but is too swiftly suppressed. A book as dry as this could well have reprinted chunks of FitzStephen verbatim. It could also have allowed itself the licence of the occasional reconstruction of family life,, or a sketch of a street scene or a section of the city. As it is, the same material is used two or three times over, and irritating gaps appear: there is little mention of the relations between London and its hinterland; there is no idea of the balance of population between rich and poor, between immigrant and resident, tradesman and servant -indeed I can find no discussion of population at all. There is nothing about early building techniques; or about the domestic relationship between, for instance, the members of an individual street or parish. Even with so little available evidence, should not the historian make an effort to paint a fuller and more coherent picture? Others have tried and succeeded.

Nonetheless, this is a work of great thoroughness. If the riddle is not solved, the clues are all there for students to pore over and unravel. And, of course, Secker and Warburg need every encouragement to proceed with this titanic series; it is no less valuable for sometimes giving us a twinge of disappointment.

Previous page

Previous page