The romance of the place

Mary Keen

THE LOST GARDENS OF HELIGAN by Tim Smit Channel FourlGollancz, £20, pp. 269 English gardens', wrote Goethe, 'are not made to a plan, but to a feeling in the head'. Until we all discovered horticulture, the point of gardens was that they touched your heart. Eighteenth-century landscapes had associations with poetry, or painting, or the classics, 19th-century ones majored in nostalgia for the cottage garden that never was. We still respond to nostalgia, but most gardens that are admired today are no more than collections of plants. I doubt that the words 'herbaceous border' could deliver any emotional charge, but say `secret garden', 'lost garden' or describe a place that might have surrounded Sleeping Beauty's tower and plenty of people will swoon. The garden at Heligan in Cornwall is not by the exacting standards of serious gardeners a Great Garden, but it is now among the most visited places in England. The melon garden with pineapple pits heated by manure hot beds is unique and fascinating, but apart from that, people do not go to see rarer rhododendrons than those in other Cornish gardens, nor for better borders and larger vegetables. They go for the romance of the place.

The only begetter of this phenomenal success is Tim Smit who spotted that a gar- den with soul and a human story was what everyone really wanted to visit. He has now written the book of the film of the restora- tion. The Secret Garden and Peter Rabbit meet Challenge Anneka is how he describes his sales pitch to interest the television companies. The book has all the energy and drive of the man who masterminded the operation. His prose is heady. `Romance', 'dream', 'childhood memories', `ghosts', 'ruins' and 'jobs from hell' crowd the pages. 'The compost bins smell warm and sweet', 'the smell of loam and damp, mixed with the faint whiff of creosote is enough to send the blood coursing through the veins'. Clearly he is entranced by the place that he rescued from oblivion.

Whether you meet the man, or read the book, or visit the 'lost gardens', only the most stony-hearted could resist the power of such an obsession. Tim Smit pulls all sorts of unlikely people into his vortex. The ex-director of the Royal Horticultural Soci- ety's garden at Wisley is now on the Heli- gan team. Planners and grant-giving bodies can deny him nothing. (He has even achieved a millennium grant for his next horticultural adventure, The Eden project.) I found the book a gripping account of how to win friends and influence people.

Human, rather than horticultural, inter- est is what Heligan is about. Everyone who worked on the project gets a mention and many are pictured potting up chicory, pick- ing carrots, clearing lakes or hacking ivy. The story is well told and the author keeps the momentum going. 'What', many people have asked Tim Smit, 'will keep people coming when the Lost Gardens of Heligan have been well and truly found?' The trou- ble with getting there', he quotes from Dorothy Parker, 'is that when you get there, there is no there, there'. It is the unattainable, the yearn appeal that sells Heligan. It may be going too far to suggest that Heligan is an anagram of healing or that it is a metaphor for redemption and discovery. It is hard to admit that there is something spiritual about gardens. Tim Smit has been brave enough to stick his soul on his sleeve and invite us all to come and see it. We can pretend to disapprove, but in our heart of hearts we know he has revealed something about gardens that most people are never lucky enough to dis- cover.

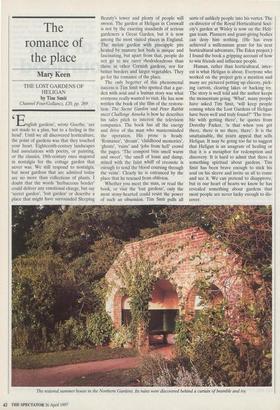

The restored summer house in the Northern Gardens. Its ruins were discovered behind a curtain of bramble and ivy.

Previous page

Previous page