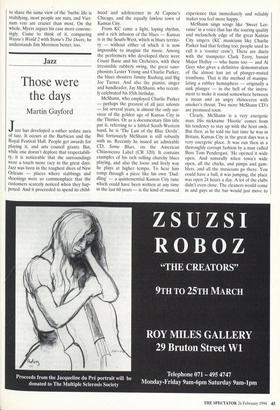

Jazz

Those were the days

Martin Gayford

Jazz has developed a rather sedate aura of late. It occurs at the Barbican and the Royal Festival Hall. People get awards for playing it, and arts council grants. But, while one doesn't deplore that respectabili- ty, it is noticeable that the surroundings were a touch more racy in the great days. Jazz was born in the toughest dives of New Orleans — places where stabbings and shootings were so commonplace that the customers scarcely noticed when they hap- pened. And it proceeded to spend its child-

hood and adolescence in Al Capone's Chicago, and the equally lawless town of Kansas City.

From KC came a light, loping rhythm, and a rich infusion of the blues — Kansas is in the South-West, which is blues territo- ry — without either of which it is now impossible to imagine the music. Among the performers who developed there were Count Basie and his Orchestra, with their irresistible rubbery swing, the great saxo- phonists Lester Young and Charlie Parker, the blues shouters Jimmy Rushing and Big Joe Turner. And also the pianist, singer and bandleader, Jay McShann, who recent- ly celebrated his 85th birthday.

McShann, who employed Charlie Parker — perhaps the greatest of all jazz soloists

— for several years, is almost the only sur- vivor of the golden age of Kansas City in the Thirties. Or as a documentary film title put it, referring to a fabled South-Western band, he is 'The Last of the Blue Devils'. But fortunately McShann is still robustly with us. Recently he issued an admirable CD, Some Blues, on the American Chiaroscuro Label (CR 320). It contains examples of his rich rolling churchy blues playing, and also the loose and lively way he plays at higher tempo. To hear him romp through a piece like his own Dad- dling' — a quintessential Kansas City tune which could have been written at any time in the last 60 years — is the kind of musical

experience that immediately and reliably makes you feel more happy.

McShann sings songs like 'Sweet Lor- raine' in a voice that has the soaring quality and melancholy edge of the great Kansas City singers (KC musicians like Charlie Parker had that feeling too; people used to call it a 'rooster crow'). There are duets with the trumpeter Clark Terry, bassist Major Holley — who hums too — and Al Grey who gives a definitive demonstration of the almost lost art of plunger-muted trombone. That is the method of manipu- lating a rubber hemisphere — originally a sink plunger — in the bell of the instru- ment to make it sound somewhere between a moan and an angry rhinoceros with smoker's throat. Two more McShann CD's are promised soon.

Clearly, McShann is a very energetic man. His nickname `Hootie' comes from his tendency to stay up with the hoot owls. But then, as he told me last time he was in Britain, Kansas City in the great days was a very energetic place. It was run then in a thoroughly corrupt fashion by a man called Boss Tom Pendergast. 'He opened it wide open. And naturally when town's wide open, all the chicks, and pimps and gam- blers, and all the musicians go there. You could have a ball, it was jumping, the place was open 24 hours a day. A lot of the clubs didn't even close. The cleaners would come in and guys at the bar would just move to one side and let them clean it, then go back and carry on drinking.'

McShann was a fan of the king of boogie woogie pianists, Pete Johnson, and his musical partner, the singer Joe Turner. 'In a club old Joe would tell Pete to roll 'em, and Pete would play for twenty minutes, then Joe sang for twenty minutes, then told Pete to roll 'em again — and there you were, that was the first set, one hour, one tune. And they'd carry on like that all night. There were so many musicians from North, South-East and West, but once they got to Kansas City, they all got that KC stamp on them.'

Among the native performers from Kansas City itself, however, was Charlie Parker, whose novel, beautiful alto-saxo- phone sound McShann heard coming out of the open doorway of a club one day. 'It sounded good, I wanted to check it out, hear more of it.' Eventually, Parker joined the big band that McShann formed in 1939, and stayed, on and off, for three years. He was a slight handful then — 'He was a young cat, the sap was rising' — but had not yet approached the heroic level of dis- sipation which brought him to an early grave. McShann remembers him with pride and affection.

Does he miss those days? 'Oh yes,' he answers, 'It was an era, you understand, an era'. It was an era, I find, that you do not have to have experienced to miss.

Previous page

Previous page