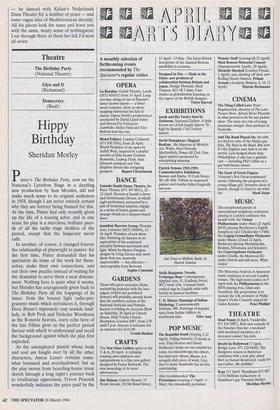

Theatre

The Birthday Party (National Theatre) Glyn and It (Richmond) Democracy (Bush)

Hippy Birthday

Sheridan Morley

Pinter's The Birthday Party, now on the National's Lyttelton Stage in a dazzling new production by Sam Mendes, did not make much sense to its original audiences in 1958, though I am never entirely certain why they are forever being blamed for this. At the time, Pinter had only recently given up the life of a touring actor, and in one sense his play is a merciless, brilliant paro- dy of all the tacky stage thrillers of the period, except that the Inspector never calls.

In another, of course, it changed forever the relationship of playwright to punter: for the first time, Pinter demanded that his spectators do some of the work for them- selves, make their own connections, sort out their own puzzles instead of waiting for the dramatist to serve them a neat denoue- ment. Nothing here is quite what it seems, but Mendes has courageously given back to The Birthday Party all the trappings of its times: from the bouncy light radio-pro- gramme music which introduces it, through Dora Bryan's supremely cosy seaside land- lady, to Bob Peck and Nicholas Woodeson as the B-movie heavies, every echo here of the late Fifties gives us the perfect period flavour with which to understand and recall the background against which the play first exploded.

As the unemployed pianist whose body and soul are fought over by all the other characters, Anton Lesser remains some- what bemused and overshadowed: but as the play moves from boarding-house revue sketch through a long night's journey back to totalitarian oppression, Trevor Peacock wonderfully indicates the price paid by the innocent bystander to the thugs of the state. Best of all, though, apart from Dora Bryan's wondrous return to the height of her comic form, is the moment when the set slides back into a street full of houses just like it: in every window a light, in every room some other kind of nameless terror.

Currently on a national tour, Ken Hoare's G411 and It is an intriguing slice of Hollywood history that never quite becomes the Wildean comedy of bad man- ners within which Ken Hoare has framed it.

In about 1926 Elinor Glyn, the romantic novelist who had by then taken up resi- dence in the Californian hills as an adviser on historical epics ('ducal castles do not have a line of spittoons, even gold ones, down the middle of the drawing room') formed an unholy alliance with Clara Bow, whom she rightly saw as the spirit of the new age. Collette had her Gigi, Anita Loos her Lorelei Lee, and Elinor her Clara: but Hoare's often funny and touching script gives neither Penelope Keith nor Samantha Spiro the chance to do more than sketch in some shadowy figures for Richard Cot- trell's agile classy production. A clearing in the woods near Washing- ton, July 1863: Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson are there to slug it out with two soldiers, a deserter from the South and a blinded, dying veteran from the North. What is at issue here is not, however, the Civil War itself, but rather the soul of America and the fight for decency.

John Murrell's ambitious, talky Democracy (Bush) is an 'issue' play but the issues themselves are so vast that they are inclined to bring any drama to a grinding halt while we embark on yet another pan- theistic debate.

On the one hand, Murrell gives us big Walt, forever ready to see the best in men as he shelters soldiers in his woodland glade and talks of the miracles of earthly love, even as his beloved boys are dying around him. On the other hand there is craggy, disbelieving Waldo, who has the evidence of his own eyes to remind him of man's inhumanity to man and the ultimate foolishness of any real optimism, especially in wartime.

John Dove's production, on a wonderful- ly, realistic set by Robert Jones complete with growing grass and forest pools on that tiny Bush stage, sets up Hugh Ross as the Cynical Emerson against Stanley Townsend's chubby, prattling Whitman and lets them talk it out as the two soldiers (Nick Waring and Johnny Lee Miller) form their audience and ultimately the living and dying figureheads of their argument. But Murrell never commits to one side or the other, never indicates whether he favours Emerson' ' worldly cynicism over Whitman's smug, ambling paternalism: a writers' conferenc in the middle of a bloody conflict is pt therefore to seem something of an 1idulgence, especially When half its audience is actually bleeding to death during the debate.

Previous page

Previous page