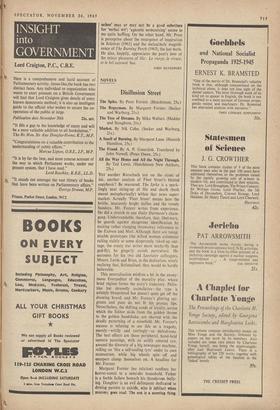

Disillusion Street

The Spike. By Peter Forster. (Hutchinson, 25s.) NOVELS YET another Rorschach test on the street of ink, another analysis of Fleet Street's blotted copybook? Be reassured. The Spike is a spark- lingly neat sizing-up of life and death (both meant metaphorically) within that news super- market. Actually 'Fleet Street' means here the brittle, insecurely bright dailies and the trendy Sundays. Mr. Forster writes from experience. He did a stretch in one Daily Dartmoor's chain- gang. Understandable, therefore, that, libel-wary, he guards against dangerous identification by making rather clanging throwaway references to the Express and Mail. Although there are recog- nisable prototypes (the wilted woman columnist railing stalely at some desperately raked-up out- rage, the crusty star writer more tetchy-fly than gad-fly), he gingerly avoids portraiture. He accounts for his two old Spectator colleagues, Messrs. Levin and Brien, in the dedication, wisely realising that, fictionalised, they would be hardly believable.

This neutralisation misfires a bit in the anony- mous Everyeditor of the morality play, whose brief regime forms the story's trajectory. Philis- tine but shrewdly assimilative—the type is astutely blueprinted but doesn't quite get off the drawing board, and Mr. Forster's glinting epi- grams and puns do not fit his prosaic lips. Nevertheless, the shifting sands of loyalty, across which the Editor skids from the golden throne to the golden handshake, are charted with the deadly patterning of a minefield. Mr. Forster's success is refusing to see this as a tragedy, merely—wittily and Cuttingly—as melodrama. The best effects are those peripheral, hand-held camera pannings, with an acidly amused eye, around the diversity of a big newspaper machine, roiling on 'like a self-sealing tyre' under its own momentum, while big wheels spin off and usurpers clamp themselves on. A headline for Mr. Forster.

Margaret Forster (no relation) confines her horror-comic to a semi-det household. Father is a feeble failure beneath his thunderous bully- ing. Daughter is an evil delinquent dedicated to driving parents to suicide, who is jubilant when mummy goes mad. The son is a sneering thing.

While there doubtless are families so poisoned and mutilated by hatred, violence played at such stereophonic volume numbs one's receptiveness. Miss Forster writes capitally, rattling along with vigorous confidence. However, she is too breezily indifferent to modulation, to winning the reader's trust in her case by reasoning rather than brute force.

With The Tree of Dreams, more bitterness, weeping and passion black as volcanic smoke: but it is love that so batters Mika Waltari's character, and not in a sustained holocaust. Still, they sink teeth, nails and knives into each other, and derive much sombre Finnish delight from the torment and the remorse. 'I'm a fish in a net. I flounder, I struggle,' bewails one lover. 'Fire and earth,' cries another—both elements that reek from these powerful and desolating stories.

After a few pages of Market, I thought: 'Yes, wow, and all that—but this is stuff one splashes down in hot blood at nineteen.' Then, checking, I found that Mr. Cohn, who works for the Observer's 'Briefing' team, is nineteen. It is a Briefing' about What's On In Limbo London, a phantasmagoria of back-street stews. Mr. Cohn is precociously gifted, with a flamboyance fuelled on Naked Lunch high octane, but unhelp- ful emphasis is lavished upon bodily fluids and solids. I think by now genital detail has been adequately delineated. Leaving the flag fluttering bravely on the conquered Mons Veneris, on- ward now to non-erogenous zones.

A comparative peace laps in with the rest of the novels. Margaret Lane's story concerns an etiolated belle-lettrist who glides in to die in a Morocco bower. Audience to his swan-song is an expatriate assortment whose individual problems are threaded into the nappy texture. It is 'rich tapestry' prose, done with a many-splendoured grace, but, I fear, over-stately with finesse. In The Fraud a stranger is discovered unconscious on a Paris shopkeeper's doorstep. Succoured in the living-room, he smooth-talks his way into the couple's trust and under their daughter's petti- coat. 'An intricate work of art,' announces the blurb. Certainly it is intricate, as is a hair- stylist's braiding, and of similar trifling decora- tiveness. Really, it is an anecdote elaborated in the mode of eighteenth-century pornography (the flowery archness, the smirk behind the hand, the set-piece reminiscences), but pausing fastidiously short of bawdy.

Ted Lewis is naturalistic, to the opposite ex- treme in his somewhat pedestrian record of art- students' mating rituals. It seems faithful, in a Saturday Night way, to the adolescent flux around provincial record shops and Golden Eggs, yet irresistible Vic's ploughing through girl after girl is rhythmical without having much orchestration. His jealousy-wrecked idyll with Janet drones on flat and predictable as a pop ballad. A rather square La Ronde.

KENNETH ALLSOP

Previous page

Previous page