Back to school

Patrick Cosgrave

"Oh my God," said my favourite Tory MP on Monday — the day the House of Commons re-assembled — as he looked at the Evening Standard front page story on the Stock Market dive, "what are we going to do?" By " we " he meant not the Government so much as the Conservative Party which felt, on Monday, as though something nasty and unexpected had blown Up and hit it in the face. After all, given the Prime Minister's rapturous reception by press and public opinion alike, on announcing Phase Two of the Prices and Incomes policy, the Tories were surely entitled to hope for a little relief from the hostile pressure they endured in the Closing days of the last session; and entitled, too, to feel that they could sail serenely on during the next few weeks at least, confident in the support of public Opinion, and sustained by a nation willing to row together in support of the freeze as Mr Heath had asked. That bubble of selfconfidence and hope was burst by the behaviour of the Stock Market on Monday; and the Prime Minister's extreme irritability with Mr Wilson at Question Time on Tuesday reflected his awareness that the Prices and incomes situation — and, by linplication, the political situation itself — looked like getting out of hand again. The Tories are worried in the first week back at school.

The obverse of this coin is the fact that the Labour Party have their tails up. Many Were the hugger-mugger conversations that took place in the week before Parliament came back, wondering what to do — about Harold, about Ted, about their reactions to the new phase of incomes Policy. The more thoughtful Labour Party People were, moreover, uneasily conscious of the fact that the 'Prime Minister's new incomes policy looked like the old Labour Model — only better. One senior Shadow Minister was telling his friends and colleagues — anyone who would listen, indeed — that Ted was increasingly Showing himself to be a better politician than Harold, adept at stealing other People's clothes and expert at pinching the limelight in the national interest — a national interest that, conveniently, turned out to be a party interest as well. Labour, at the end of last week, were set to come back to Westminster•armed and prepared for another period of endless bickering about themselves, futile anger with Mr Heath, and tiresome questioning about Mr Wilson. That they have performed during the first few days in glad and confident heart can be put down, not merely to the fact that the Stock Exchange misbehaved this week and so embarrassed the Government severely, but also to the fact that Mr Wilson made a commanding Speech on future policy at Leith last Saturday.

Mr Wilson himself has for some time believed that, the shock of the last general election being over, he had the measure of the Prime Minister. He was irritated that none of his colleagues believed him, and even more that his own self confidence had made no dent whatever in the armour of Tory self-esteem. To be sure, there have always been senior Tories willing to consider the proposition that this Government, of all recent administrations, was the most likely to be defeated at the next election. But such people were considering a proposition self-evidently academic — self-evidently because, in their view, Mr Wilson was so very busted a flush. They were also influenced in their view by the extraordinary serenity the Prime Minister has maintained throughout every reversal: that serenity has sustained both his ministers and his party, even when individuals disliked him, or thought he was doing wrong. Now, as one minister said to me this week, "People are beginning to laugh at Ted. He's getting more and more like Wilson — when he was Prime Minister. Only he hasn't got the charm."

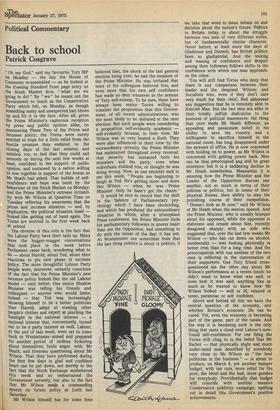

It would be nice to record that the shift in the balance of Parliamentary psychology which I have been chronicling, and which has produced the extraordinary situation in which, after a triumphant Press conference, the Prime Minister finds his parliamentary followers in poorer heart than are the Opposition, had something to do with the issues of the day: it has not. At Westminster one sometimes feels that the last thing politics is about is politics, if we take that word to mean debate on and decision about the nation's future. Politics in Britain today is about the struggle between two men of very different styles, but of fundamentally similar character. Never before, at least since the days of Gladstone and Disraeli, has British politics been so gladiatorial. And the waxing and waning of confidence and despair among their followers follows shifts in the confidence with which one man approaches the other.

You will still find Tories who deny that there is any comparison between their leader and the despised Wilson; and Socialists who, even if they don't care very much for their chief, find abhorrent any suggestion that he is remotely akin to Kentish Man. But the two men are alike in their totally selfish dedication to the business of political manoeuvre: the thing that once made Mr Heath different, an appealing and passionate belief in his ability to save the country and a willingness to sacrifice himself in the national cause, has long disappeared under the stresses of office. He is now concerned with holding on to power, as Mr Wilson is concerned with getting power back. Men can be thus preoccupied and still be great ministers: but it is a saddening decline in Mr Heath nonetheless. Meanwhile it is amazing how the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition discuss one another, not so much in terms of their policies or politics, but in terms of their physical fitness, their ability to stay the punishing course of their competition. "Doesn't look so fit now," said Mr Wilson of Mr Heath when the session opened. And the Prime Minister, who is usually brusque about his opponent, while the opponent is elaborate and ornate about him, recently disagreed sharply with an aide who suggested that, over the last few weeks Mr Wilson — who has cut down on alcohol, incidentally — was looking physically in better trim than for a long time. And the preoccupation with one another of the two men is reflected in the conversation of their supporters. One Tory friend crossquestioned me the other day about Mr Wilson's performance at a recent lunch: he didn't want to know what was said, or even how it was said, anything like as much as he wanted to know how Mr Wilson looked — well or ill, relaxed or tense, paranoiac or self confident.

Above and behind all this we have the central question of the economy, and whether Britain's economic ills can be cured. Yet, even the economy is becoming part of the game, part of the tussle. And the way it is becoming such is the only thing that casts a cloud over Labour's newfound self-confidence. For one thing the Tories still cling to is the belief that Mr Barber — that physically slight and much under-rated man described by somebody very close to Mr Wilson as "the best politician in the business" — is about to produce, on March 6, yet another bumper budget, with tax cuts, more relief for the poor, the blind and the halt, more goodies for everybody. Providentially that budget will coincide with another massive Conservative publicity campaign, spelling out in detail this Government's positive achievements.

Previous page

Previous page