Surrealistic in our dreams but bourgeois in our worries

Frances Partridge

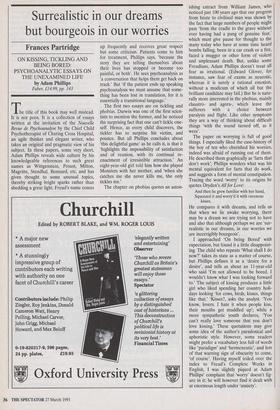

ON KISSING, TICKLING AND BEING BORED: PSYCHOANALYTIC ESSAYS ON THE UNEXAMINED LIFE by Adam Phillips Faber, £14.99, pp. 143 he title of this book may well mislead. It is not porn. It is a collection of essays written at the invitation of the Nouvelle Revue de Psychoanalyse by the Chief Child Psychotherapist of Charing Cross Hospital, an agile thinker and elegant writer, who takes an original and pragmatic view of his subject. In these papers, some very short, Adam Phillips reveals wide culture by his knowledgeable references to such great names as Wittgenstein, Proust, Milton, Magritte, Stendhal, Bonnard, etc, and has given thought to some unusual topics, thereby striking bright sparks rather than shedding a great light. Freud's name comes up frequently and receives great respect but some criticism. Patients come to him for treatment, Phillips says, 'because the story they are telling themselves about their lives has stopped or become too painful, or both'. He sees psychoanalysis as 'a conversation that helps them get back on track.' But `if the patient ends up speaking psychoanalysis we must assume that some- thing has been lost in translation, for it is essentially a transitional language,'

The first two essays are on tickling and phobias. Darwin was one of the first scien- tists to mention the former, and he noticed the surprising fact that one can't tickle one- self. Hence, as every child discovers, the tickler has to surprise his victim, and pounce. But all Phillips concludes about 'this delightful game' as he calls it, is that it 'highlights the impossibility of satisfaction and of reunion, with its continual re- enactment of irresistible attraction.' An eight-year-old girl told him how she played Monsters with her mother, and 'when she catches me she never kills me, She only tickles me.'

The chapter on phobias quotes an aston-

Ishing extract from William James, who noticed just 100 years ago that our progress from brute to civilised man was shown by the fact that large numbers of people might pass 'from the cradle to the grave without ever having had a pang of genuine fear,' which must give pause for thought to the many today who have at some time heard bombs falling, been in a car crash or a fire, faced a mugger or other form of violent and unpleasant death. But, unlike some Freudians, Adam Phillips doesn't treat all fear as irrational. (Edward Glover, for instance, saw fear of exams as neurotic, whereas it is surely a rational emotion, without a modicum of which all but the brilliant candidate may fail.) But he is natu- rally more interested in the phobias, mainly claustro- and agora-, which leave the sufferers with a choice between paralysis and flight. Like other symptoms they are a way of thinking about difficult things 'with the sound turned off, as it were'.

The paper on worrying is full of good things. I especially liked the case-history of the boy of ten who cherished his worries, indeed was afraid of running out of them. He described them graphically as 'farts that don't work'; Phillips wonders what was his mental equivalent for farts that do work, and suggests a form of mental constipation. Tracing the word 'worry' to its origins he quotes Dryden's All for Love: And then he grew familiar with her hand, Squeezed it and wony'd it with ravenous

kisses.

He compares it with dreams, and tells us that when we lie awake worrying, there may be a dream we are trying not to have and also that although perhaps we are 'sur- realistic in our dreams, in our worries we are incorrigibly bourgeois'.

I approached 'On being Bored' with expectation, but found it a little disappoint- ing. The child who repeats 'What shall I do now?' takes its state as a matter of course, but Phillips defines it as a 'desire for a desire', and tells us about an 11-year-old who said 'I'm not allowed to be bored. I wouldn't know what I was looking forward to.' The subject of kissing produces a little girl who liked spending her country holi- days looking 'for cows, birds, kisses, things like that."Kisses?, asks the analyst. 'You know, lovers. I hate it when people kiss, their mouths get muddled up'; while a more sympathetic youth declares, 'You can't really love someone that you don't love kissing.' These quotations may give some idea of the author's paradoxical and aphoristic style. However, some readers might prefer a vocabulary less full of words like 'paradigm' and 'hermeneutic', and less of that warning sign of obscurity to come, 'of course'. Having myself toiled over the index to Freud's Complete Works in English, I was slightly piqued at Adam Phillips' complaint that 'worry' doesn't fig- ure in it; he will however find it dealt with at enormous length under 'anxiety'.

Previous page

Previous page