ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Victorian Landscape Watercolours (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, till 12 April)

'The innocence of the eye'

Celina Fox

In his Academy Notes for 1857, Ruskin compared the Society of Painters in Water- Colours to the firm of Fortnum & Mason, supplying the demand of the British public for 'Potted Art, of an agreeable flavour, suppliable and taxable as a patented com- modity'. Tempting though it is today to see the denizens of Piccadilly as sole purveyors of such fare, a choice selection of Victorian landscape watercolours freshly arrived in Birmingham should not be missed. It draws not only on the rich reserves of the Yale Center for British Art, where the show originated, and Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, where it will close, but on an enterprising range of public and private collections extending from the Orkneys to Maidstone. Most of the works are unfamil- iar, yet almost all are in pristine condition and their jewel-like colours are set off by the hang on rich red walls. The exhibition IS a pleasure to contemplate.

More surprisingly, perhaps, it would have given pleasure to Ruskin, whose spirit per- meates the show. Delighting in the very act Of seeing, he advocated the artist's recovery of 'the innocence of the eye', working not from generalised principles but from direct observation, penetrating the meaning of nature by 'rejecting nothing, selecting noth- ing, and scorning nothing; believing all things to be right and good, and rejoicing always in the truth'. In these works, a minute, stippled technique augmented by bodycolour is used to record intricate gra- dations of light, shade and colour, largely replacing the subtle ambiguities and pic- turesque generalities of early English watercolours built up from broad brush- strokes and transparent washes.

Though advocated by Ruskin in his high- 1Y influential Elements of Drawing (1857) and commonly thought of as Pre- Raphaelite', such methods were in use 20 Years earlier. The first watercolour in the Show is a miraculously preserved work by Ruskin's teacher, William Henry Hunt, culled from the stores of the Harris Muse- um, Preston. 'Pollard Elm and Village Pound, Hambledon' is almost hyper-realist In its close observation of gnarled bark, knotted wood and dense greenery, yet it was painted in 1833. Other artists seem to anticipate Ruskin's favourite subject mat- ter, for nobody had a monopoly on nature. Thus, as the exhibition demonstrates, artists as disparate as Samuel Palmer and William James Miller were busy depicting rocky banks and exposed roots long before Ruskin pronounced 'all banks are beautiful things'. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that a 'hands and knees' approach to nature, as Christopher Newall describes it In the exceptionally informative catalogue (Victorian Landscape Watercolours, Hudson Hills Press, New York, in association with the Yale Center for British Art; available at the exhibition for the special price of £24.95), took off in the 1850s with Ruskin as chief proselytiser. Though his own mag- nificent study, 'In the Pass of Kil- liekrankie', 1857, is not in the Birmingham showing, Alfred William Hunt is a worthy follower, supplying some of the finest watercolours in the exhibition. 'Mountain Landscape — Cwm Trifaen', of 1856, depicts the desolate uplands of Snowdonia, the shafts of intricately stratified rock breaking through the thin brown turf and a threatening veil of mist half-enveloping the

starkly jagged summit.

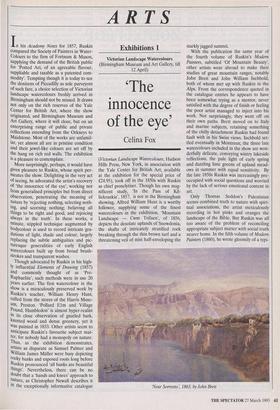

With the publication the same year of the fourth volume of Ruskin's Modern Painters, subtitled 'Of Mountain Beauty', other artists went abroad to make their studies of great mountain ranges, notably John Brett and John William Inchbold, both of whom met up with Ruskin in the Alps. From the correspondence quoted in the catalogue entries he appears to have been somewhat trying as a mentor, never satisfied with the degree of finish or feeling the poor artist managed to inject into his work. Not surprisingly, they went off on their own paths. Brett moved on to Italy and marine subjects, retaining something of the chilly detachment Ruskin had found fault with in his Swiss views. Inchbold set- tled eventually in Montreux; the three late watercolours included in the show are won- derfully delicate, conveying wintry lakeside reflections, the pale light of early spring and dazzling lime greens of upland mead- ows in summer with equal sensitivity. By the late 1850s Ruskin was increasingly pre- occupied with social questions and worried by the lack of serious emotional content in art.

Only Thomas Seddon's Palestinian scenes combined truth to nature with spiri- tual associations, the artist meticulously recording in hot pinks and oranges the landscape of the Bible. But Ruskin was all too aware of the problem of reconciling appropriate subject matter with social truth nearer home. In the fifth volume of Modem Painters (1860), he wrote gloomily of a typi- 'Near Sorrento', 1863, by John Brett cal Highland landscape, 'I see a man fish- ing, with a boy and a dog — a picturesque and pretty group enough certainly if they had not been there all day starving. I know them, and I know the dog's ribs also, which are nearly as bare as the dead ewe's; and the child's wasted shoulders, cutting his old tartan jacket through.' One does not need to be a new art historian to find precious little depiction of suffering in the mountain ranges, deep woods and babbling brooks which made up the bulk of subject matter for Victorian landscape watercolourists. Nor did they display much concern for the realities of a landscape which was increas- ingly under threat. As Ruskin recognized, theirs was a landscape with `no gasworks, no waterworks, no mowing machines, no sewing machines, no telegraph poles, no vestige, in fact, of science, civilization, eco- nomic arrangements, or commercial enter- prise !!!'.

It is true that George Pryce Boyce depicts a colliery in the distance of one work, but with a lot of pure landscape and blackberry pickers in the foreground. In his otherwise traditional prospect of Worces- ter, John Gilbert includes a train puffing away from the outskirts. A.W. Hunt bril- liantly celebrates the battle between tech- nology and nature in his view of Tynemouth Pier, the sea and spray crash- ing over the man-made assemblage of stone, wooden beams and iron rails. But the only watercolour in the show with an overtly political message is Albert Good- win's fiery 'Sunset in the Manufacturing Districts'. It shows an industrial wasteland, the water in the foreground not a still pool but a stagnant swamp, the trees not lushly verdant but stark stumps: a shattered roof- less dwelling bears the ironic notice, 'TO LET THE HOLE OF THIS PLACE'.

It makes a sharp contrast to the nostalgic vision of England purveyed by Helen Allingham and Kate Greenaway, yet Ruskin recognized their value in recording a threatened rural way of life. The haymak- ers and cattle drovers painted unselfcon- sciously by Peter De Wint in the 1840s become poignant as survivors — 'Greek gods in smock-frocks', as someone unkindly dubbed Fred Walker's labourers. Streatley Mill with its timber frame, brick walls, mul- lioned windows and irregular tiled roofs, as portrayed by George William Boyce on a still summer evening, is a timeless record of the vernacular architecture of the Thames valley. J.W. North's depiction of a manor farm in the Quantocks quietly encapsulates in one small image a vanishing world: Tudor homestead, haystack, fishpond, kitchen garden, timber, woods, servants. It is, as in the title given to another Goodwin watercolour — the usual woods, flowers and water well clear of the manufacturing districts — 'A Pleasant Land'.

The last watercolour in the show dates from after the first world war, some indica- tion of the strength of the Victorian land- scape tradition. Birket Foster is still driving cattle before Ben Nevis in 1891, Poynter producing a highly detailed watercolour of Isola San Giulio in 1898. It is with a jolt that one realises what was going on else- where in the art world by this time. Ruskin had come to see the style he did so much to foster as 'the oppression of plethoric labour', art preserved in aspic. True, there was a revival in the 1870s of watercolours with the breadth and vigour we associate with David Cox Senior and the clear wash- es of Peter De Wint. But from the evidence. of this show it never quite took off. Instead, for a breath of fresh air, of pure unstippled unmuddied colour, we have to look to America, to the watercolours of Whistler, Homer and Sargent, whose exhibition in this country is long overdue.

Previous page

Previous page