IN FROM THE COLD

John Simpson meets some men from an

organisation whose official existence is about to be acknowledged, after 80 years

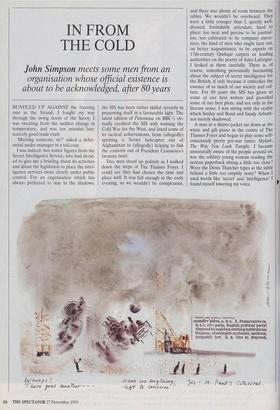

BUNDLED UP AGAINST the freezing rain in the Strand, I fought my way through the swing doors of the Savoy. I was sweating from the sudden change in temperature, and was ten minutes late: scarcely good trade-craft.

`Meeting someone, sir?' asked a defer- ential under-manager in a tail-coat.

I was indeed: two senior figures from the Secret Intelligence Service, who had decid- ed to give me a briefing about its activities and about the legislation to place the intel- ligence services more clearly under public control. For an organisation which has always preferred to stay in the shadows,

the SIS has been rather skilful recently in presenting itself in a favourable light. The latest edition of Panorama on BBC-1 vir- tually credited the SIS with winning the Cold War for the West, and listed some of its tactical achievements, from (allegedly) spiriting a Soviet helicopter out of Afghanistan to (allegedly) helping to fish the contents out of President Ceausescu's lavatory bowl.

Two men stood up politely as I walked down the steps of The Thames Foyer. I could see they had chosen the time and place well. It was full enough in the early evening, so we wouldn't be conspicuous, and there was plenty of room between the tables. We wouldn't be overheard. They were a little younger than I, quietly well- dressed, formidably articulate, hard to place: too neat and precise to be journal- ists, too cultivated to be company execu- tives, the kind of men who might turn out, on better acquaintance, to be experts on 17th-century Qashqai carpets or leading authorities on the poetry of Jules Laforgue. I looked at them carefully. There is, of course, something perennially fascinating about the subject of secret intelligence for the British, if only because it embodies the essence of so much of our society and cul- ture. For 80 years the SIS has 'given us some of our best writers and provided some of our best plots; and not only in the literary sense. I was sitting with the reality which Smiley and Bond and Sandy Arbuth- not merely shadowed.

A man in a dinner-jacket sat down at the white and gilt piano in the centre of The Thames Foyer and began to play some self- consciously pretty pre-war tunes: Skylark, The Way You Look Tonight. I became unnaturally aware of the people around us; was the solitary young woman reading the serious paperback sitting a little too close? Were the Denis Thatcher types at the table behind a little too emptily noisy? When I used words like 'secret' and 'intelligence' found myself lowering my voice.

The two men were notably understated: there was nothing about winning the Cold War, no Ceausescu excreta. Their SIS was a recognisable adjunct of Whitehall, cost- conscious, careful, imbued with the public service ethos. The SIS welcomed the bill which would place it under parliamentary scrutiny: since it was firmly under political control anyway, it could only help the SIS if this were made clear in the most public way possible, by an Act of Parliament.

We dealt with the differences between the CIA, most people's idea of an intelli- gence organisation, and the SIS. The CIA is essentially a very large machine for gath- ering and processing information, a signifi- cant player in the complicated internal politics of Washington, its head a powerful Administration figure in his own right. The CIA has a view on most subjects, compet- ing with other big departments like the State Department if they take a different view. The SIS, by contrast, does not deal with research and does not process the information it gathers. It is equivalent to just one part of the CIA, the directorate of operations, but it is only a fraction of the size of that section. Small, said the two men in The Thames Foyer, was beautiful: post-Philby, the SIS prides itself on its abil- ity to keep secrets. Nor did the SIS have to involve itself in Whitehall's political bat- tles; it presented raw intelligence to the Joint Intelligence Committee, which then oversaw its dissemination to the relevant ministries. Because the SIS budget was relatively small the service was usually glad if the Foreign Office or some other arm of government could take on a task instead of the SIS. Perhaps all this represented the precise actuality, perhaps it represented more of an aspiration. Which of us, in defending some organisation for which we work, has not preferred to concentrate on the spirit of the thing, and forgotten the moments when it wasn't quite like that?

There was, they insisted, no scope for running an independent SIS policy. Since what they did frequently had the potential to create immense embarrassment for the government, the SIS worked under the strictest of controls. It didn't assassinate people, and no such plan had been moot- ed in their experience of more than two decades. The formidable Baroness Park, now revealed as a leading figure in the SIS (having been the head of Somerville Col- lege, Oxford, and, rather more thought- provokingly, a governor of the BBC), made it clear in Monday's Panorama what the SIS did do: it works where necessary on factions inside the groups or govern- ments which it has penetrated, and if the faction favoured by the SIS chooses to get rid of its rivals in some fairly conclusive way, no doubt the SIS sits back and lets it happen. In Whitehall-speak, its penetra- tion activities are known as 'interventions% presumably the thinking is that there is no 'The Select Committee on government waste will now come to order.' point in penetrating, say, a terrorist ring without trying to put it out of business for good, There is a certain John Buchan logic to the SIS; Sir Richard Hannay would have approved of the idea of 'intervention'.

The SIS employs about 1,900 people all told, including drivers and office cleaners. It is not largely composed of colonels' daughters: its current headquarters, at Century House in Lambeth, contains blacks and Asians and young men with ponytails and ear-rings, and the kind of secretaries you might find in any large organisation. As for intelligence officers, there are believed to be between 300 and 350 of them. During the Cold War more than a third were involved in work related to the Soviet bloc, but the SIS has always believed in covering the world, and it has people in most of the significant countries. The most important function of an SIS intelligence officer abroad is to recruit and operate agents; not simply to garner gener- al information.

What constitutes success or failure for the SIS is difficult for outsiders to assess. The revelation that the KGB station chief in London, Oleg Gordievsky, was an SIS agent was in one sense a failure, since he was discovered and had to be brought out of Russia. That operation, indeed, was remarkably successful, but the SIS had lost an agent who might have risen to become operational chief of the KGB. An ideal SIS agent is recruited in his or her 30s, works upwards through the organisation and reports faithfully for the SIS over an entire career: at the end of which he or she retires, full of honours, on a healthy pen- sion. Agents are more useful if they remain in place.

It is all a distinctly dubious business, which involves breaking other countries' laws as a matter of course. Those countries, one assumes, include Iraq, Iran and Libya; North Korea and China, which make nuclear proliferation possible; India, Pak- istan and South Africa, which have nuclear programmes; countries building a chemical or biological warfare capability; areas like the Balkans, where British troops and British aid agencies are operating, or the former Soviet Union; and the drugs and dirty money industries. The ending of the Cold War has not, in the view of men like those I was sitting with, brought the SIS a peace dividend of any kind. Indeed, they maintained, a smaller British defence capa- bility enhanced the need for better intelligence.

The pianist in The Thames Foyer had moved on to The King and I, the young woman was still reading her book, the Denis Thatcher types were louder than ever. The two men from the SIS and I agreed the ground rules, which would allow me to describe our surroundings; though they would probably have preferred the whole thing to be entirely off the record. Shall We Dance? was starting up. I walked back out into the cold.

Previous page

Previous page