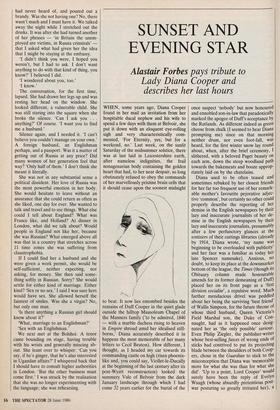

SUNSET AND EVENING STAR

Alastair Forbes payS tribute to

Lady Diana Cooper and describes her last hours

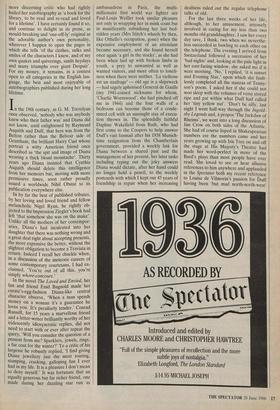

WHEN, some years ago, Diana Cooper found in her mail an invitation from her hospitable ducal nephew and his wife to spend a few days with them at Belvoir, she put it down with an eloquent eye-rolling sigh and very characteristically com- mented, 'For Eternity, yes; but for a weekend, no.' Last week, on the sunlit Saturday of the midsummer solstice, there was at last laid in Leicestershire earth, after nameless indignities, the frail nonagenarian body containing the golden heart that had, to her near despair, so long obstinately refused to obey the commands of her marvellously pristine brain cells that it should cease upon the soonest midnight to beat. It now lies entombed besides the remains of Duff Cooper in the quiet glade outside the hilltop Mausoleum Chapel of the Manners family ('to be admired, 1840 — with a marble duchess rising to heaven in Empire shroud amid her idealised still- borns,' Diana accurately described it in happens the most memorable of her many letters to Cecil Beaton). How different, I thought, as I headed my car towards its commanding castle on high (risen phoenix- like and, you could say, Viollet-le-Ducally at the beginning of the last century after its post-Wyatt reconstruction) looked the summery Vale of Belvoir from the dark January landscape through which I had come 32 years earlier for the burial of the once suspect 'nobody' but now honoured and ennobled son-in-law that paradoxically marked the apogee of Duff's acceptance by the Rutlands. As different indeed as green cheese from chalk (I seemed to hear Diana prompting me) since on that morning neither drum, nor even foot-fall, was heard, for the first winter snow lay round about, when, after the brief ceremony, I slithered, with a beloved Paget beauty on each arm, down the steep woodland path towards the bakemeats and booze approp- riately laid on by the chatelains. Diana used to be often teased and sometimes rebuked by her closest friends for her far too frequent use of her remark- able mother's favourite pejorative adjec- tive 'common', but certainly no other could properly describe the reporting of her demise in the English newspapers by their lazy and inaccurate journalists of her de- mise in the English newspapers by their lazy and inaccurate journalists, presumably after a few perfunctory glances at the sottisiers of their cuttings libraries (already by 1914, Diana wrote, 'my name was beginning to be overloaded with publicity' and her face was a familiar as today her late Spencer namesake). Anxious, no doubt, to keep its place at the downmarket bottom of the league, the Times (though its Obituary column made honourable amends for its former demeaning of Duff) placed her on its front page as a 'first division socialite', a repulsive word. Much further mendacious drivel was peddled about her being the surviving 'best friend' of Wallis Simpson, for the future throne of whose third husband, Queen Victoria's Field Marshal son, the Duke of Con- naught, had as it happened once desig- nated her as 'the only possible' saviour. Even Philip Ziegler, the publisher-writer whose best-selling fasces of wrong ends of sticks had contrived to put its projecting blade between the shoulders of both Coop- ers, chose in the Guardian to stick to the misconception that Diana was 'memorable more for what she was than for what she did'. 'Up to a point, Lord Cooper' would surely have been the reply of Evelyn Waugh (whose absurdly pretentious post- war posturing so greatly irritated her), a more discerning critic who had rightly hailed her autobiography as 'a book for the library, to be read and re-read and loved for a lifetime'. I have certainly found it so, and continue to delight in its prose, as mould-breaking and 'one-off-ly' original as the adorable author's own personality, wherever I happen to open the pages in which she tells 'of the clothes, sulks and smiles of the characters I knew, and of my own quakes and quiverings, sunlit heydays and many triumphs over giant Despair'. For my money, it remains, in a contest open to all categories in the English lan- guage, the best and most enjoyable of autobiographies published during her long lifetime.

In the 19th century, as G. M. Trevelyan once observed, 'nobody who was anybody knew who their father was' and Diana did not know, until enlightened by Raymond Asquith and Duff, that hers was from the Belton rather than the Belvoir side of Grantham, the brilliant Harry Cust whose portrait a witty American friend once described as 'the spit and image of Diana wearing a thick blond moustache'. Thirty years ago Diana insisted that Cynthia Asquith should delete this intelligence from her memoirs but, moving with more permissive times, soon rather proudly issued a worldwide Nihil Obstat to its publication everywhere else. In by far the best of published tributes, by her loving and loved friend and fellow melancholic Nigel Ryan, he rightly ob- jected to the impression Ziegler's book had left 'that somehow she was on the make'. Unlike all the mothers of her contempor- aries, Diana's had inculcated into her daughter that there was nothing wrong and a great deal right about accepting presents, the more expensive the better, without the slightest obligation to become a Traviata in return. Indeed I recall her chuckle when, in a discussion of the meteoric careers of some contemporary courtesans, I had ex- claimed, 'You're out of all this, you're simply whore-concours.'

In the novel The Loved and Envied, her fan and friend Enid Bagnold made her curate's-egg-fashion Diana-like central character observe, 'When a man spends money on a woman it's a guarantee he loves you. It's peculiarly tender.' Conrad Russell, for 15 years a marvellous friend and a letter-writer brilliantly worthy of her iridescently idiosyncratic replies, did not need to start with or ever after repeat the query, `Will you consider the question of a present from me? Sparklers, jewels, rings, a fur coat for the winter?' To a critic of his largesse he robustly replied, 'I find giving Diana jewellery just the most roaring, stamping, cracking, galloping fun I ever had in my life. It is a pleasure I don't mean to deny myself.' It was fortunate that an equally generous but far richer friend, one made during her dazzling star run as ambassadress in Paris, the multi- millionaire first world war fighter ace Paul-Louis Weiller took similar pleasure not only in wrapping her in mink coats but in munificently subsidising her last bed- ridden years (Mrs Stitch's wheels by then, like Othello's occupation, gone) when the expensive employment of an attendant became necessary, and she found herself once again 'a girl in the stocks', as she had been when laid up with broken limbs in youth, a prey to unwanted as well as wanted visitors, and more often to loneli- ness when there were neither. `La viellesse est un naufrage' — old age is a shiprweck — had sagely aphorised General de Gaulle (my 1941-coined nickname for whom, `Charlie Wormwood', she had pinched off me in 1944) and the four walls of a bedroom can become those of a conde- mned cell with an unsought stay of execu- tion thrown in. The splendidly faithful Daphne Wakefield from Bath, who had first come to the Coopers to help answer Duff's vast fanmail after his 1938 Munich- time resignation from the Chamberlain government, provided a weekly link for Diana between a shared past and the management of her present, her later tasks including typing out the joky answers Diana would dictate, after her hand could no longer hold a pencil, to the weekly postcards with which I kept our 45 years of friendship in repair when her increasing deafness ruled out the regular telephone talks of old.

For the last three weeks of her life, although, to her amusement, intensely involved in caring for my less than two months old granddaughter, I saw her every day save, I think, two when we neverthe- less succeeded in bawling to each other on the telephone. The evening I arrived from Switzerland followed a succession of her tad nights' and, looking at the pale light in her east-facing window, she asked me if it were morning. `No,' I replied, 'it is sunset and Evening Star,' upon which she fault- lessly completed all the stanzas of Tenny- son's poem. I asked her if she could not woo sleep with the volumes of verse stored ripe and pat within what Duff had called her 'tiny yellow nut'. 'Don't be silly, last night I went half-way through the Ingold- sby Legends and, a propos 'The Jackdaw of Rheims', we went into a long discussion of Jim Crow on both sides of the Atlantic. She had of course lisped in Shakespearian numbers ere the numbers came and her years growing up with Iris Tree on and off the stage at His Majesty's Theatre had made her word-perfect in more of the Bard's plays than most people have ever read. She loved to see or hear allusive references to him anywhere and applauded in the Spectator both my recent reference to Louise de Vilmorin's passion for Duff having been 'but mad north-north-west' and the aptness of Mark Amory's opening of his review of the latest book by her old mummer chum Sir Larry Olivier: 'Who would have thought the old man had so much ink in him?'

On the last night of her life, I spent an hour and a half with her until the time drew near for Schlafengehen (she adored famil- iar music and Strauss's Last Songs not least). In that time we covered, as always, a vast range and enchainement of topics, speaking of cabbages and kings, of past and present. She recited, without any- where 'drying', the C of E catechism, but we agreed that we would both fare rather better with a judicious cocktail of the pre-Judeo-Christian or Muslim `Do unto others as ye would that they do unto you', with a bit of Mozart and Schikaneder's Magic Flute (Die Wahrheit, Die Wahrheit — Truth, only Truth), Strauss and Hof- mannsthal's Marschallin with her (Heut oder Morgen and Leicht, Leicht, Muss Man Sein) and lastly Beethoven's Fidelio for being as she indeed was herself, Absolute for Friendship and Love. We also laughed together a lot, using for 'country matters' what she once called 'the coarse tongue which suits gusto and gives no offence'. l was suddenly and quite unwontedly struck by the seriousness of her beauty of counte- nance. Her love-in-the-mist eyes fixed me searchingly and she said more than once that she had something very important to impart to me and as often that she had momentarily forgotten what it was. I said it could wait till morning. I believe she had a strong premonition that her death was at last, as I knew it to be, near. She, who had always absurdly but sincerely dismissed herself as '0 for Ordinary' and first wanted to entitle her autobiography How I got away with it then disparaged what she called her 'rotten form'.

I told her truthfully that I found her company, as I had always done, the best in the world. (And we had been out together in all kinds of weather under all manner of skies, from pigging it together in a time of troubles in the Atlas Mountains with bur- nous'd Berbers she invariably dubbed 'Bib- lical Brutes' to King George VI's Bucking- ham Palace, where, 'flown with insolence and wine' and catching sight of me seated next to his Queen Consort, she let loose an all too audible cry to her escort, 'Just look where our Ali has got to now!'

I can best apply to her the words she herself used of another great friend we were lucky enough to share, Emerald Cunard: 'Her song was of wisdom and wit and love, sung with a lark's abandon and exuberance. She forced people to live and give and ask for more of the elixir she had distilled and was proffering.'

I do not think there is need to brood too much about something else she also wrote: `If I were told by God (directly) that Eternity was perfectly charming for all, I should worry that perhaps I wasn't going to like that kind of thing'.

Previous page

Previous page