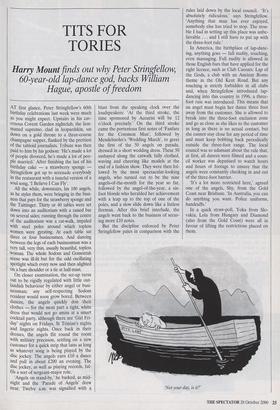

TITS FOR TORIES

Harry Mount finds out why Peter Stringfellow,

60-year-old lap-dance god, backs William Hague, apostle of freedom

AT first glance, Peter Stringfellow's 60th birthday celebrations last week were much as you might expect. Upstairs in his cav- ernous Covent Garden nightclub, the lion- maned supremo, clad in leopardskin, sat down on a gold throne to a three-course champagne supper, flanked by the prettiest of the tabloid journalists. Tribute was then paid to him by his godson: `He's.made a lot of people divorced, he's made a lot of peo- ple married.' After finishing the last of his birthday cake — a strawberry sponge Stringfellow got up to serenade everybody in the restaurant with a tuneful version of a soul song, 'I Believe I Can Fly'.

All the while, downstairs, his 100 angels, as he styles them, were bringing in the busi- ness that pays for the strawberry sponge and the Taittinger. Thirty or 40 tables were set down into an auditorium with a raised bar on several sides; running through the centre of the auditorium was a cat-walk, impaled with steel poles around which topless women were gyrating. At each table sat three or four businessmen. And dancing between the legs of each businessman was a very tall, very thin, usually beautiful, topless woman. The whole Sodom and Gomorrah scene was ill-lit but for the odd oscillating spotlight which every now and then alighted on a bare shoulder or a tie at half-mast.

On closer examination, the set-up turns out to be rigidly regulated with little out- landish behaviour by either angel or busi- nessman; any self-respecting Sodom resident would soon grow bored. Between dances, the angels quickly don their clothes — for the most part a tight, white dress that would not go amiss at a smart cocktail party, although there are 'Girl Fri- day' nights on Fridays, St Trinian's nights and lingerie nights. Once back in their dresses, the angels flit round the room with military precision, settling on a new customer for a quick strip that lasts as long as whatever song is being played by the disc jockey. The angels earn £10 a dance and pull in about £200 an evening. The disc jockey, as well as playing records, ful- fils a sort of sergeant-major role.

`Angels on stand-by,' he barked, as mid- night and the 'Parade of Angels' drew near. Twelve a.m. was signalled with a blast from the speaking clock over the loudspeakers: 'At the third stroke, the time sponsored by Accurist will be 12 o'clock precisely.' On the third stroke came the portentous first notes of 'Fanfare for the Common Man', followed by Mendelssohn's 'Wedding March', to greet the first of the 50 angels on parade, dressed in a short wedding dress. These 50 sashayed along the catwalk fully clothed, waving and cheering like models at the end of a fashion show. They were then fol- lowed by the most spectacular-looking angels, who turned out to be the nine angels-of-the-month for the year so far, followed by the angel-of-the-year, a six- foot blonde who heralded her achievement with a leap up to the top of one of the poles, and a slow slide down like a listless fireman. After this brief interlude, the angels went back to the business of secur- ing more £10 notes.

But the discipline enforced by Peter Stringfellow pales in comparison with the rules laid down by the local council. 'It's absolutely ridiculous,' says Stringfellow. `Anything that man has ever enjoyed, somebody else has tried to stop. The trou- ble I had in setting up this place was unbe- lievable . . and I still have to put up with the three-foot rule.'

In America, the birthplace of lap-danc- ing, anything goes — full nudity, touching, even massaging. Full nudity is allowed in those English bars that have applied for the right licence, such as Club Caesars: Lap of the Gods, a club with an Ancient Rome theme in the Old Kent Road. But any touching is strictly forbidden in all clubs and, when Stringfellow introduced lap- dancing into this country in 1996, a three- foot rule was introduced. This means that an angel must begin her dance three foot away from the customer. She is allowed to break into the three-foot exclusion zone and go as close as she likes to the customer as long as there is no actual contact, but she cannot stay close for any period of time and must keep bobbing back periodically outside the three-foot range. The local council was so adamant about the rule that, at first, all dances were filmed and a coun- cil worker was deputised to watch hours and hours of footage to ensure that the angels were constantly checking in and out of the three-foot barrier.

`It's a lot more restricted here,' agreed one of the angels, Shy, from the Gold Coast near Brisbane. 'In Australia, you can do anything you want. Police uniforms, handcuffs.'

In a quick straw-poll, Yoka from Slo- vakia, Lola from Hungary and Diamond (also from the Gold Coast) were all in favour of lifting the restrictions placed on them.

Not your day, is it?' `Peter treats us very well,' said Cass, one of the few English angels. 'He could apply for a licence for full nudity — we'd be happy doing it — but he doesn't think it's right for the clientele. Still, I think every- one wants to get rid of the three-foot rule.'

Stringfellow, a committed Tory, is scep- tical as to whether the laws will change. The central tenet of the Conservative mini-manifesto, published in September by William Hague, was freedom: 'freedom from big government, bureaucratic con- trol, and all the targets, and gimmicks, and bossy, nannying, Whitehall interference that are the hallmark of the present gov- ernment'. Stringfellow is keen on main- taining his Tory links: sitting at his private table at the party was one of the whips in Ted Heath's 1970 administration, Lord Bethell. But even a Tory election victory would be unlikely to change things, Stringfellow thought.

`I'm afraid it's just the way this country has always been,' he said. 'I've just read a fascinating book — The History of Obsceni- ty Laws in Britain. I thought book-burning belonged to the Middle Ages but, you know what? Book-burning went on until the 1940s.'

Even though obscenity laws will proba- bly survive a Tory election victory, Stringfellow will be delighted if the Tories win, and is confident that they will.

`New Labour are in total disarray,' he said. 'If Tony Blair was honest, he'd admit that he's a federal European but, although I think he's a man of principle, he's dropped his principles. He can't come out and say how committed he is to the euro. I wish he would. I'd love to hear a proper argument as to why we should join.'

Stringfellow himself is, in fact, a dedicat- ed European — he spends most weekends on his yacht in Majorca — but he cannot see a federal Europe happening for anoth- er 50 years.

`It's bound to happen eventually. After all, Britain was once fragmented and run `I'm afraid we don't have business-class horses. They're all economy.'

by a lot of different kings. And Germany was once Saxony and all those other states. So we should let the Europeans do what they do best — squabble among them- selves — wait until it's calmed down, and then go in.

`But, at the moment, there's no point in going in. John Major was right when he said, "Let's wait and see; we'll never go in unless it's perfect for Great Britain." Labour seem to be saying, "Let's wait a bit but go in anyway, however bad it's look- ing." That seems to be the difference between Labour and the Tories.'

Born in Sheffield, the son of a steel- worker, Stringfellow has been a Tory since his youth. 'If I was honest, I'd say, at heart, I'm a Liberal Democrat, or a democrat, really, but they've got no chance of ruling and never have had in my lifetime. So I've always been a Tory, even though all the steelworkers in Sheffield were Labour to a man, my dad included. But what I didn't like was the way the Labour party never encouraged you to better yourself. Now, even my dad has come round to my way of thinking. He's seen how well I've done as a businessman — he never owned a house until the 1970s when I bought him one. And now he's as right-wing as they come; spits blood at the mention of the Labour party.' Stringfellow is not quite so extreme in his criticism of the government. 'Business in the club is great at the moment. But then the business climate was handed to Labour on a plate by John Major. I think they've gone wrong on everything else. Whenever I do talks at Oxford or Cam- bridge University, I always say that more private health and private education are the way forward. Both my children and both my grandchildren are privately edu- cated. By all means, have a system for those who can't afford it, but for those who can, they should pay for themselves. People spend loads on everything else houses, cars, going out — but they don't think it's their job to pay for their health, which is kind of important.'

His other great bugbear is capital gains tax. 'It kills business,' he says, speaking from his boat in the Balearics a few days after his party. 'Out here,' he says, 'there are lots of tax exiles who do not want to be tax exiles. They're not big money — £5 million, not £50 million — but still they're taxed so highly that they stay out here, loafing around, messing about with boats, when they're exactly the sort of people who should be in England creating more jobs.'

Stringfellow, an avowed fan of the works of John Locke, has aired his views at sever- al Conservative party gatherings: he hosted a fund-raising party at his club to help the Tories fight last year's successful. European elections. He was due to appear on an episode of Question Time, but it was post- poned because of the Kosovo crisis. Still, he is not tempted to take his political interests further and run for office.

`I'm having too much fun doing what I'm doing — my 60th birthday was the best night of my life. I can't imagine it would be as enjoyable being an MP.'

Previous page

Previous page