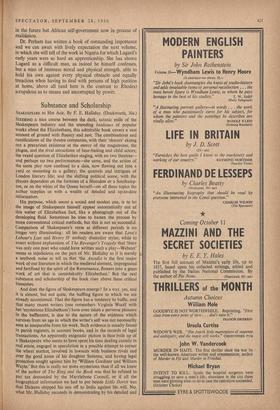

BOOKS

The Two Sides of Colonialism

BY LORD ATTLEE THERE are two names written large in the history of Africa, Rhodes and Lugard, that typify two contrasting aspects of the impact of Europeans on Africa. Cecil Rhodes•, the dreamer of Empire, consumed with a lust for power, and Lugardt, the practical idealist inspired by the spirit of service to the African.

To many people of the present day, colonialism is the evil exploitation of the darker races in the interests of the white people; and that this is so is largely due to the activities of Rhodes and his associates—which were confined to the two closing decades of the nineteenth century, for, as Marshal Smuts often said to me, British imperialism died in the South African War. Lugard represents an older and more enduring tradition. Dr. Perham shows how, after the ending of the slave trade by Europeans, the humanitarian impulse of the evangelicals turned to missionary work. Africa offered a spectacle of 'heathen lands afar where black darkness brooded,' and the response to this call from Britain was very greit. Middle-class Britain was inspired by the courage and devo- tion of such men as Livingstone. Lugard carried on this tradition in the secular sphere and was one of the inspirers of that conception of trusteeship by the whites for the less- developed peoples which is now the accepted doctrine of colonial policy.

Successive British Governments, not excepting that of Disraeli right down to that of Lord Salisbury, were opposed to territorial expansion in Africa, whether the urge came from idealists who wished to bring to an end the exploitation of the Africans by Arab slave traders or from Cape-to-Cairo imperialist dreamers like Rhodes. Joseph Chamberlain was the first statesman of the imperialist school.

In these two books we have the story of two men both reared in English parsonages. Both came somewhat by chance on the African stage. Between the two there could hardly be a greater contrast. Dr. Gross, who is by no means in love with his hero, traces in considerable detail Rhodes's story from the time when as a very young man he came to the diamond diggings in Kimberley. We see this strange man, with his love of Oxford and devotion to the classics. competing with the shady adventurers for control of the mines, seeking money as the source of power. For it is here that he is distinguished from the rest of the money-making crowd that swarmed into South Africa. He sought wealth as a means of attaining his ideal, which was that of a great British Empire in Africa, stretch- ing from Egypt to the Cape. He saw it as part of a dream of a pax Britannica embracing the whole world. He was utterly unscrupulous as to means and intensely dictatorial in his management of his great financial enterprises. We see his * RHODES OF AFRICA. By Felix Gross. (Cassell, 25s.) t LucAnn : The Years of Adventure, 1858-1898. By Margery Perham. (Collins, 42s.) early dreams of uniting the British and Afrikander elements in South Africa breaking down before the obstinacy of President Kruger and his own impatience. We see him becom- ing more and more ruthless as power corrupted until the Jameson Raid, for which he held a large measure of responsi- bility, put an end to his career. We have glimpses too of the England of the Nineties with its vulgarity and money worship.

All this is told in a style of florid journalese doubtless suited to its subject-matter. Rhodes, though not entirely indifferent to the interests of the Africans, clearly regarded them as lesser breeds without the law and did not shrink from cold-blooded massacre when the Matabele stood in his way. Nevertheless there were elements of greatness in Rhodes to which his biographer hardly does justice. His administration in Cape Colony did many wise things which are dismissed in a paragraph. Even his courageous meeting with the Matabele in the Matoppo Hills is related with a covert sneer. How much of his errors were due to his health, which made him a man in a hurry, is an interesting speculation.

Very different is the study of Lugard by Dr. Perham, who was a personal friend of her subject and is an outstanding authority on African affairs. Dr. Perham shows the early influences on Lugard, especially that of his remarkable mother. She describes the career of the able young soldier and then the turning-point of his life, a disappointment in love which nearly unbalanced his mind and sent him to Africa caring little for his life. She describes admirably the position in Africa, and, with her personal knowledge, brings the African scene vividly before us. Here on the cast coast Lugard found his vocation to work for the good of the Africans, and, first of all, in the suppression of the slave trade. With little support from Downing Street, and despite endless frustrations, he eventually got a mission to Uganda. In the course of these years the paths of Rhodes and Lugard crossed, and, after hopes of help -from Rhodes, he suffered from the caprice of the empire-builder. In these years of endurance, his strength of• mind and body was shown.

Lord Salisbury was moved not by any desire for Empire nor even for philanthropic enterprises, but from the rivalry of foreign powers, especially Germany. Africa was partitioned into spheres of influence and Uganda was secured for Britain by Lugard just in time. We see Lugard managing his caravans of Africans and treating with Africans in a spirit of justice and humanity—in stark contrast to the methods of Karl Peters, the notorious German explorer, and of Cecil Rhodes's henchmen. Dr. Perham deals very fully with Lugard's administration in Uganda and the controversy that arose therefrom, and is notably fair-minded iii her judgement.

In both these books one meets with the Chartered Company, that curious Victorian device whereby governments sought to evade responsibility while furthering capitalist enterprises and imperialist expansion on the cheap. In Uganda we find the curious mixture of trading interest and missionary enter- prise; in Ngamiland the motive was commercial, as it was in Nigeria, although here it was directed by a genius, Goldie; while in Rhodesia it was the instrument of a single man's ambition. There was a growing factor of opposition to other powers, German, Boer and French. The atmosphere of the period with its imperialist enthusiasm is admirably recalled and is of special interest to one like myself, who can well remember the Jameson Raid and the Fashoda incident. Lugard, who later was to find his true vocation as a great colonial administrator, was forced to take service in these commercial ventures, but throughout this, early period one discerns the future statesman who saw not only trusteeship in the future but African self-government now in process of realis'ation.

Dr. Perham has written a book of outstanding importance and we can await with lively expectation the next volume, in which she will tell of the work in Nigeria for which, Lugard's early years were so hard an apprenticeship. She has shown Lugard as a difficult man, as indeed he himself confesses. but a man of immense moral and physical strength, able to hold his own against every physical obstacle and equally tenacious when having to deal with persons of high position at home, above all (and here is the contrast to Rhodes) scrupulous as to means and uncorrupted by power.

Previous page

Previous page