HERESY IN THE PUNJAB

In the last days of the

,election campaign, Dhiren Bhagat

finds Sikh attacking Sikh

Barnala BARNALA (pop. 28,000) is a small, dirty town in southern Punjab, the sort of place people come from rather than go to, the headquarters of a subdivision of district Sangrur, one of the twelve districts in the truncated Punjab. The constituency for the state legislative assembly, a 'semi-rural' one, is larger: there are some 80,000 votes here. But even that's nothing much: there are another 116 constituencies in the state, all equally large.

This time round the constituency has been invested with a particular signifi- cance. A month ago Sant Harchand Singh Longowal, the moderate Sikh leader, was assassinated in Shepur, a village only one and a half rupees (ninepence) away from the town if you take a bus. And his successor as the leader of the Akali Dal, a 60-year-old lawyer-politician, Surjit Singh Barnala, is (as his name suggests) a Barna- la boy who's made good. The most heavily guarded man in India after Rajiv, Barnala is the Akali candidate from Barnala. In these elections the Akalis are fighting Sikh gress but their real enemies are the Sikh extremists who want the polls boycotted.

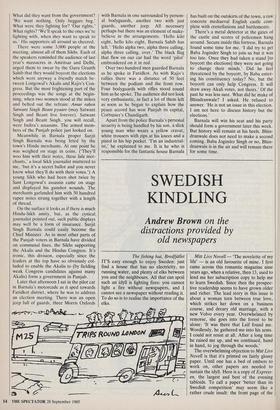

I came here on Sunday, the penultimate day of campaigning, in a jeep full of saffron-turbaned boys. Among the Sikhs saffron is the colour of sacrifice and by the mad logic of the Punjab today it's the terrorists who are making the biggest sacrifices. But these boys weren't terror- ists, at any rate they weren't terrorists on duty. They were courteous, soft-spoken supporters of Baba Joginder Singh, Bhin- dranwale's father and the leader of the breakaway United Akali Dal which is urging people to boycott the elections. (They don't consider themselves break- away: the jeep flew two flags: one was a faded Akali pennant, the other a black flag with the word 'boycott' spelt out in white Gurumukhi letters.) Baba Joginder Singh was to address a meeting in Barnala's constituency that day, very much a rival meeting as Barnala was going to address another meeting at the same time only seven kilometres away. Whenever we passed a group of villagers the boys in the jeep would scatter printed copies of a photograph. In several villages I saw children fight for these, the photo- graph had become a collector's item, there were young boys who had collected fistfuls. The photograph showed the Akali candi- date for the parliamentary constituency of Sangrur, Balwant Singh Ramoowalia, bowing before a man in a white turban, about to touch his feet. The man in the white turban had his hand raised, as if to bless. My neighbour in the jeep, a Ludhiana landlord who had made his money manufacturing agricultural imple- ments, laughed. 'This is the most damaging photograph we could have got. The man in the white turban is Gurcharan Singh, the last leader of the Nirankaris. Ramoowalia was taking his blessing.' I know the Nirankaris are considered a heretical sect by most Sikhs, in fact Bhindranwale began his career in the late Seventies locked in conflict with the Nirankaris. Even so, my neighbour's enthusiasm seemed absurd. He went on: 'Someone once asked Ramoowalia about the photograph. You know what Ramoowalia said? He said something had fallen on the floor, he was picking it up. Picking it up, the man said If he was picking it up then why was the Nirankari's hand raised? Ha ha ha ha ha.'

To be fair to the people of the Punjab, weightier issues obsess them, but this is a good indication of what really moves ex- tremists in the Baba Joginder Singh camp: a violent hatred of heresy and a disgust for the slipperiness of politics. But the rest of the Punjab is not as interested in such matters. The children in the villages may collect these 'embarrassing' photographs but Ramoowalia will almost certainly win his seat in parliament.

I spoke to Baba Joginder Singh before he went on stage to address the gathering. His supporters, riding tractors and trolleys, were shouting in the background: Bhin- dranwala aaoonga, Khalistan leyaaoonga (Bhindranwale's going to come, he's going to bring Khalistan). 'You heard what they're saying?' he said, a smug smile spreading across his face. 'No, I'm not saying it, they're saying it.' Did he still think Bhindranwale was alive? Yes. What government would he prefer, an Akali one or a Congress one? A government of truth, justice and righteousness. (Most of his replies were this kind of pious waffle.) What did they want from the government? 'We want nothing. Only beggars beg.' What were they fighting for? 'Our rights.' What rights? 'We'll speak to the ones we're fighting with, when they want to speak to us.' His supporters all around us cheered.

There were some 3,000 people at the meeting, almost all of them Sikhs. Each of the speakers reminded the audience of last year's massacres in Amritsar and Delhi, urged them to swear by the Guru Granth Sahib that they would boycott the elections which were anyway a friendly match be- tween Longowal's Akalis and Rajiv's Con- gress. But the most frightening part of the proceedings was the songs at the begin- ning, when two women stood at the mikes and belted out the refrain: Amar rahen Satwant Singh Beant pyaare (may Satwant Singh and Beant live forever). Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, you will recall, were Indira's assassins. The armed mem- bers of the Punjab police just looked on.

Meanwhile in Barnala proper Surjit Singh Barnala was being feted by the town's Hindu merchants. At one point he was weighed on stage in coins. (`They'll woo him with their notes, these lala mer- chants,' a local Sikh journalist muttered to me, 'but it's a secret ballot and you never know what they'll do with their votes.') A young Sikh who had been shot twice by Sant Longowal's assassin came on stage and displayed his gunshot wounds. The merchants garlanded him with 50 hundred rupee notes strung together with a length of thread.

On the surface it looks as if there is much Hindu-Sikh amity, but, as the cynical, journalist pointed out, such public displays may well be a form of insurance. Surjit Singh Barnala could easily become the Chief Minister. As in most other parts of the Punjab voters in Barnala have divided on communal lines, the Sikhs supporting the Akalis and the Hindus Congress. It's ironic, this division, especially since the leaders at the top have so obviously col- luded to enable the Akalis to (by fielding weak Congress candidates against many Akalis) form a government in Punjab.

Later that afternoon I sat in the pilot car in Barnala's motorcade as it sped towards Faridkot district, where he was to address an election meeting. There was an open jeep full of guards, three Morris Oxfords with Barnala in one surrounded by person- al bodyguards, another two with just guards, another jeep. All necessary perhaps but there was an element of make- believe in the arrangements. 'Hello kilo eight, hello kilo eight, Barnala Sahib has left.' Hello alpha two, alpha three calling, alpha three calling, over.' The black flag that flew on our car had the word 'pilot' embroidered on it in red.

Over two hundred men guarded Barnala as he spoke in Faridkot. As with Rajiv's rallies there was a distance of 50 feet between the podium and the front row. Four bodyguards with rifles stood round him as he spoke. The audience did not look very enthusiastic, in fact a lot of them left as soon as he began to explain how the peace accord has won Punjab its capital, Corbusier's Chandigarh.

Apart from the police Barnala's personal security is being handled by his son, a slick young man who wears a yellow cravat, white trousers with zips at his knees and a pistol in his hip pocket. 'I'm an industrial- ist,' he explained to me. It is he who is responsible for the fantastic house Barnala has built on the outskirts of the town, a raw concrete mediaeval English castle com- plete with crenellations and battlements.

There's a metal detector at the gates of the castle and scores of policemen hang around. Secure inside this fortress, Barnala found some time for me. 'I did try to get Baba Joginder Singh to join us but it was too late. Once they had taken a stand [to boycott the elections] they were not going to change their minds.' Did he feel threatened by the boycott, by Baba enter- ing his constituency today? No, but the boycott can only help Congress. It will draw away Akali votes, not theirs.' Of the past he was less sure. What did he make of Bhindranwale? I asked. He refused to answer. 'He is not an issue in this election. I am not here to discuss history but the elections.'

Barnala will win his seat and his party should form a government later this week. But history will remain at his heels. Bhin- dranwale does not need to make a second coming. Baba Joginder Singh or no, Bhin- dranwale is in the air and will remain there for some time.

Previous page

Previous page