Wild and whirling words

Philip Hensher

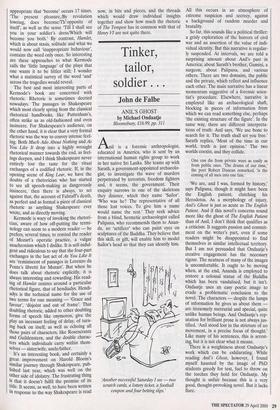

SHAKESPEARE'S LANGUAGE by Frank Kermode Allen Lane, £20, pp. 320 Shakespeare's language isn't, as it turns out, really the subject of this book. Plenty of interesting books could be written on the subject of the English language as man- ifested in Shakespeare; on his characteristic syntactical structures, his grammatical innovations, prosody and morphology. Plenty more could be written on the atti- tudes to linguistic use evident in the plays and poems. Frank Kermode has written quite an interesting book, but its interest in Shakespeare's language more or less stops short at figures of rhetoric and semantics. A serious investigation of Shakespeare's language would find it necessary to retain Shakespeare's spelling, as manifested in the early printed texts, and to talk about it; Kermode's interests are narrow enough to be served by the modernised Riverside text. Exploration of meaning, however, is a good big subject all on its own, and in the event supplies Kermode with quite enough to be going on with.

Kermode sees, quite rightly, that there is something superfluous about Shake- speare's interest in language and rhetoric. Quite often, one senses that the linguistic invention is so energetic that the con- straints of rational meaning are too tight for it; now and then, the plays throw up a character whose linguistic exuberance serves no real end except itself, as with many of the clowns, or even one, like Pis- tol, who comes on and talks rolling non- sense. As we go on, this invention in rhetoric seems rather to increase than any- thing, and there are several late plays, like Coriolanus or The Winter's Tale, where the rhetoric is so highly wrought and inward that from time to time the characters can't even understand each other. Jachimo in Cymbeline is a main offender: 'It cannot be i' th'eye, for apes and monkeysf Twixt two such shes would chatter this way, and/Con- temn with mows the other, nor i' the judg- ment/For idiots in this case of favour would/Be wisely definite.' Imogen in response says what half the audience, sure- ly, is starting to wonder: 'What's the mat- ter? Are you well?'

This characteristic difficulty is not unique to Shakespeare, but the fact of difficulty is more central to his language than it is to that of many of his contemporaries. The difficulty of Donne springs from a commit- ment to 'harshness', and to the slowly elab- orating simile. Spenser can be hard because of his fascination with the hermet- ic mysteries; Jonson, because he delights in learning and the abstruse allusion. Shake- speare's difficulty, on the other hand, is a fact intrinsic to his language. Words are rudely shifted from one part of speech to another, so that 'woman' can as readily be a verb as a noun; syntax is compacted to the utmost point of ambiguity. The aston- ishing thing is that some of the most highly- wrought poetry in English was produced to be listened to, and the passages in Cori- olanus which now baffle the patient reader were, apparently, taken in by the groundlings as if it were EastEnders.

Shakespeare's Language has some rewarding insights and deft readings, but I find it frustratingly structured and ulti- mately a bit unconvincing. The reader is put on the alert at the beginning when he says that there are critics who claim that 'the reputation of Shakespeare is fraudu- lent, the result of an 18th-century national- ist or imperialist plot'. I've never heard anyone say that; what plenty of people think, including me, is that the political rise of Great Britain in the 18th century had the incidental effect of transforming the lit- erary virtues which Shakespeare's culture admired into universal ones. Can anyone seriously doubt that, if the history of the Middle Ages had gone a different way and Islam triumphed in Europe, Professor Ker- mode would now be writing books about the universal genius of Averroes?

Even on his own terms, Kermode can prove rather frustrating. Kermode's point that Shakespeare's style underwent a huge shift around 1600, just before Hamlet, leads him to rattle through the earlier plays, skipping over some of Shakespeare's best things, such as the second Haul, IV play, with hardly a mention. Indeed, some of the very best things, such as most of the non- dramatic poetry, get no mention at all. After that, each of the major plays gets an essay on its own. I suppose it would be a useful approach for the sixth-former who only has to read Macbeth and has no inten- tion of reading Cymbeline, but a more pen- etrating approach would be to take a particular idea, or linguistic fact, and pur- sue it in isolation through the whole cor- pus.

That is not to say, however, that the readings of individual plays are not excel- lent. Kermode's method, often, is to take a particular word and pursue its appearances in a particular context. This is the approach demonstrated to perfection by William Empson in The Structure of Complex Words; there is a fine essay by him on 'Honesty in Othello', for instance. Kermode's insight is, characteristically, to take words which occupy a less prominent position in the play's vocabulary, which nevertheless may more persistently colour a particular lin- guistic world. It's bright to notice, for instance, how often the verb 'become' occurs in Antony and Cleopatra; with the aid of a concordance — Kermode likes these sorts of statistical survey — it is clear that it crops up much more often than in the other plays. Antony and Cleopatra is a play about flux, and also about comple- mentarity (between the political partners as much as between the lovers), and it is appropriate that 'become' occurs 17 times. 'The present pleasure,/By revolution lowring, does become/Th' opposite of itself, as well as the sense 'Till I shall see you in your soldier's dress/Which will become you both.' By contrast, Hamlet, which is about stasis, solitude and what we would now call 'inappropriate behaviour', contains the word only once. So interesting are these approaches to what Kermode calls the 'little language' of the plays that one wants it to be littler still; I wonder what a statistical survey of the word 'and' across the tragedies would reveal. The best and most interesting parts of Kermode's book are concerned with rhetoric. Rhetoric is sometimes decried nowadays. The passages in Shakespeare which most clearly spring from the classical rhetorical handbooks, like Puttenham's, often strike us as old-fashioned and even insincere. For Shakespeare's audience, on the other hand, it is clear that a very formal rhetoric was the way to convey intense feel- ing. Both Much Ado About Nothing and As You Like It drop into a highly wrought rhetorical manner towards the end, as feel- ings deepen, and I think Shakespeare never entirely lost the taste for the ritual exchanges of a codified rhetoric. If, in the opening scene of King Lear, we have the doubts of a rhetorician who has started to see all speech-making as dangerously insincere, then there is always, to set against that, the account of Falstaffs death, as perfect and as formal a piece of classical rhetoric as anything Shakespeare ever wrote, and as directly moving. Kermode is wary of invoking the rhetori- cian, aware of how off-putting the termi- nology can seem to a modern reader — he prefers, several times, to remind the reader of Mozart's operatic practice, a vulgar anachronism which I dislike. It is self-indul- gent and ridiculous to say that the four-part exchanges in the last act of As You Like It are 'reminiscent of passages in Lorenzo da Ponte's libretti for Mozart'. But when he does talk about rhetoric explicitly, it is always interesting and rewarding. His read- ing of Hamlet centres around a particular rhetorical figure, that of hendiadys. Hendi- adys is the technical name for the use of two terms for one meaning — 'Grace and favour', 'disjoint and out of frame'. That doubling rhetoric, added to other doubling forms of speech like oxymoron, give the play an incessant feeling of delay, of turn- ing back on itself, as well as echoing all those pairs of characters, like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and the double charac- ters which individuals carry within them- selves — sister/wife, uncle/father. It's an interesting book, and certainly a great improvement on Harold Bloom's shnilar journey through Shakespeare, pub- lished last year, which was well on the Other side of idolatry. The frustrating thing is that it doesn't fulfil the promise of its ?Ale. It seems, as well, to have been written 111 response to the way Shakespeare is read now, in bits and pieces, and the threads which would draw individual insights together and show how much the rhetoric of The Tempest has in common with that of Henry VI are not quite there.

Previous page

Previous page