Sail away

John Groser Salting — A Course of My Life. Edward Heath (Sidgwick and Jackson £5.50) Whatever history decides about Edward Heath, politician, sailor and now author, one thing is already certain. "He's a fighter, not a writer", as the song might have said. Which is not to say that this is a bad book — far from it; I found it ,highly readable, and it does give some small

insight into the character of this enigmatic Man.

Mr Heath's style is very direct and Sailing is a Personal record of a special period in his life when he sought to "extend" himself, and "keep a freshness for my work". The book is written SO much in the first person that it reads like one of his better (possibly impromptu) political speeches. There is inevitably, a strong element °f self justification in it even to the defence of the third Morning Cloud's last, tragic voyage. He states that one, smaller ocean racing boat got through the gale ahead of Morning Cloud, He makes no mention of the fact that a number of other Class I yachts, some Admiral's Cup kboats, on hearing the weather forecast, turned back to Burnham and one skipper (at least) expressed amazement that Mr Heath's "movement crew" should attempt the voyage to Cowes. Earlier in the book, when he describes the transition from dinghy to bigger boat sa,iling, he says that he had no one to advise him When he bought the first Morning Cloud (a '3Parkman and Stephens 34) at the Boat Show in 1959. Yet in an interview in the Times in October of that year, he told me: "I discussed the SS 34 with some friends and I decided that it Was the best buy in my range". The early pages of the book are by far the Most interesting, when he tells how he took up Sailing at the comparatively advanced age of .49, first of all crewing off his native Broadstairs 111 a local one-design class dinghy — the Foreland — before buying for £200 his own first boat in 1966, a secondhand Snipe. In 1968, Mr Heath graduated to a Fireball "and enjoyed a Heath good season with it". By this time, Mr tleath had been invited to crew on one or two ocean racers and, clearly, he had been bitten by the bigger boat bug. He wanted, as he has put it

• me, "to be more certain of my sailing" for he Was determined to keep an interest outside Politics; and music (while still his great passion arid one which he could indulge late at night or early, in the morning) was not the "physical extension,, that he felt his life needed.

In sailing terms, Mr Heath's career since January 1969 has been a staggering success s,torY. With a five-month-old boat, he took the _ulghlY coveted Ramsgate Gold Cup. That 'timmer, the first Morning Cloud won numer

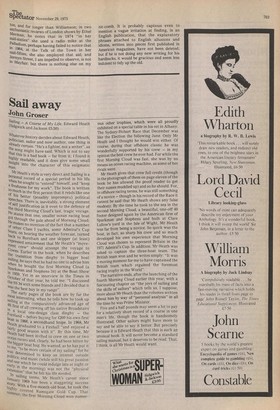

ous other trophies, which were all proudly exhibited on a special table in his set in Albany. The Sydney-Hobart Race that December was like the Election the following June. Only Mr Heath and I thought he would win either. Of course, during that offshore classic he was wonderfully supported by his crew — in my opinion the best crew he ever had. For while the first Morning Cloud was fast, she was by no means an ocean racing machine, as some of her rivals were. Mr Heath gives that crew full credit (though in the photograph of them on page eleven of the book he has allowed the proof reader to get their names muddled up) and so he should. For, in offshore racing terms, he was still something of a novice — though in his record of the Race it cannot be said that Mr Heath shows any false modesty. By the time he took to the sea in the second Morning Cloud, a beautiful, one-off 40 footer designed again by the American firm of Sparkman and Stephens and built at Clare Lallow's yard in the Isle of Wight, Mr Heath was far from being a novice. So quick was the boat, in fact, so sharp his crew and so much developed his own experience that Morning Cloud was chosen to represent Britain in the 1971 Admiral's Cup. In addition, Mr Heath was asked to captain the three-boat team. The British team won and he writes simply: "It was a moving moment for me to have captained the British team which regained the foremost racing trophy in the World". The narrative ends, after the launching of the fourth Morning Cloud earlier this year, with a fascinating chapter on "the joys of sailing and the skills of sailors" which tells us, I suppose, more about Mr Heath than the volumes written about him by way of "personal analysis" in all the time he was Prime Minister. Five and a half pounds may seem a lot to pay for a relatively short record of a course in one man's life, though the book is handsomely illustrated. Other sailors might have more to say and be able to say it better. But precisely because it is Edward Heath that this is such an unusual book. It will never become a standard sailing manual, but it deserves to be read. That, I think, is all Mr Heath would want.

Previous page

Previous page