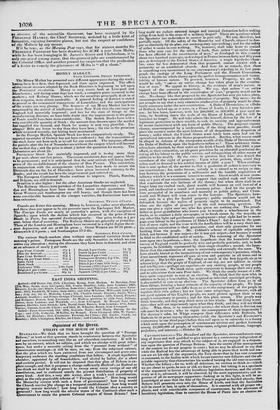

Opinion of tbe Predfi.

UTILITY OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS.

STANDARD—We think that we have brought the question of "Peerage Reform," at least as that question stands in controversy between the Spectator and ourselves, to something very like an ad absurdum conclusion. It will be seen by an extract, which we subjoin, and which we abridge with great reluc- tance, but under a necessity arising from the " pressure from without" of Conservative meetings—it will be seen, we say, from the subjoined extract, that the plan which we have extracted from our circumspect and acute con- tent's-wary embraces the startling conditions that follow. A single legislative chamber, appointed by al householders, and elected by ballot, for a short and certain period. It will not be disputed that this plan of Reform is ex- plicit enough, and that it proposes a change sufficiently Radical—so Radical as (me think we shall be able to prove) to sweep away every vestige of our old constitution, and to confound utterly the present distribution of property of every kind. And this, a very able writer, after a week's cool consideration, gives as the only practicable scheme of " Peerage Reform." How long would the Monarchy coexist with such a form of government? how long would the Church survive ;the change as a temporal establishment? bow long would property remain inviolate ? how long would the Colonies obey a country so toverned ? bow long would the adverse states of the Continent allow such a Government to retain the present Colonial empire of Great Britain ? how

lung could we endure external danger and internal distraction before seeking refuge from both in the arms of a military despot? These are questions which

the Spectator has undertaken to answer in part only. We can, therefcre, but

partially reply. Of the safety of the Monarchy and Church, exposed to dan- ger so obviously by its plan, our contemporary says nothiug ; and for the safety of either it seems to cane nothing. We, however, shall take leave to temincl those who may care for the safety of both, that. unless an entire change has been effected in the constitution of man." as developed in this country

about two hundred years ago, as developed in France between forty and fifty years ago, as developed in the United States of Amer ica, a single legislative cham. her, even far less democrat:al than that proposed, cannot coexist with a

monarchy or an established church. And here let us remark, that there

is something very inconsistent in our contemporary's rejecting in its last parse graph the analogy of the Long Parliament arid the French Convention,

when it builds its whole theory upon the perfect homogeneousness and immu- tability of human nature. To proceed, however. Propeity, we are told, would be safe, " unless an entire change has taken place in the constitu- tion of man." We appeal to history, as the evidence of man's nature, in support of the converse proposition. We say, that unless " lin entire change have been effected in the constitution of man," property would not be

safe. No change like that proposed by the Spectator has ever yet taken place,

unaccompanied by a most extensive confiecation of property. Nay more—we do not scruple to say that a very extensive confiscation of property would be abso- lutely necessary under the new constitution. A Duke of Devonshise, an a Duke

of &dried, locked up, as it were, in a House of Lorda, is a very btu mless per- son let him loose, however, with his 200,000/. or 300,000/. a year upon so-

ciety, by breaking down the walls of the House of Lords, and he will be harmless no longer. He will take others like himself, driven by the loss of a legitimate protection to their wealth, to seek its security and aggrandisement by means inconsistent with any form of public liberty. The proposed organic change, unaccompanied by a confiscation, if the thing were possible, would place the country under the most hideous of all deapotisms— the despotism of money ; under which the United States must lately have sunk had not the

agricultural interests in the States preponderated. Besides, what reason could be alleged in defence of the overgrown wealth of the Duke of Devonshire, or the Duke of Bedfoid, upon the hypothesis before us? These noblemen them- selves have admitted, by their votes on the Irish Church Bill, that 240/. a year afford, in their estimation, an adequate provision for an educated gentleman de- voting all his labour to the public service, and relinquishing all other means of addition to his wealth. By the votes in question they have also denied the sacredness of the right of property. Upon what pretext, then, could they refuse each to descend to his modest income of 240/. a year ? When confisca- tion is now spoken of, the answer is, that a gradation of orders is necessary to our constitution ; for, under favour, nobody is so absurd as to resign an ana- logy between the possessions of a millionaire and the humble acquisitions of industry which it is a common interest to secure. Great wealth is now neces- sary as a part of our constitution, to support that exalted rank and influence that constitute the sole buttress of the throne; but when there shall be no longer king nor exalted rank, great wealth will become an evil instead of a good, and confiscation a sound and necessary policy. And let the people be once persuaded of its soundness and necessity as public policy, and Chats- worth and Woburn will soon come to the hammer. The Spectator, how- ever, puts in a plea for funded property: public creditors would not be defrauded, because the rights of property ought to be maintained. But what are the rights of property ? is the still tormenting question. No man can give a right over me, who hiss given me nothing else. The grand- father or great•giandfather who leaves you to trundle a wheelbarrow in the flocks, or to conduct a daily newspaper, or to break stones by the wayside, or any other like light and gentlemanly employment—what right had he to mort- gage your labour to the gentlemen of Duke's Place? Let it come to the ques- tion of mere right, and the issue with the fundholders will be a very shrift one : the existing constitution is their guarantee, and their only guarantee for one farthing from the people. Mr. Cobbett's scheme of equitable adjustment failed, not because it was unjust—for it was not unjust—but because it would be fatal to the established order of society. The reasoning of the Spectator rests upon two hypotheses,—first, the hypothesis that the household consti- tuency of England would be perfectly wise and perfectly patriotic, and, in both respects, be faithfully represented by their single chamber ; second, the hypo- thesis that the constitution of man is universally and eternally the same. We have already hinted at the inconsistency of our contemporary's premises, which, if not inconsistent, represent all men as wise and patriotic in all times and iu all places. But let this pass. We admit so much of the first hypotlasis as to acknowledge that the people of England, of our day, are not inferior in virtue and intelligence—perhaps are superior—to any existing people, or any people that ever existed. We think them quite competent to manage their own poor, and to administer their own Poor-laws. We think the yearly tenant of a 50/_ farm quite competent to vote at an election. We think that the man who, in addition to being a householder, has acquired or inherited municipal privileges, is also entitled to vote at an election. The Spectator differs from us in all these things, brining a lower estimate of the capacity of the people. We hope our contemporary will not differ from us as to the competency of the people to regulate their own police ; but we have some misgivings. However, with all our good opinion of the English people, we must protest against their or any people's competency to govern ; and for this plain reason. The people may think honestly, and they may think more or less wisely. But one thing is cer- tain—they will act impetuously upon what they think, and they will not think alike. Who, then, is to comet their errors,—for where there is division one- side must be in error ; who to repair the consequences of their impetuosity? For decency's sake, let Whigs compose their differences with Radicals, let Radicals be at peace among themselves (vide the Spectator's and Examiner's controversy in our third page) before they call upon us to subscribe to a theory which rests upon the assumption of cousuuninate wisdom and perfect harmony among 24,000,000 of people, of various races, religious professions, language, prejudices, and interests.— October 24.

C0NST1TUTI0NAL—The Standard and the Spectator, two combatants cun-, fling of fence and well qualified to give interest to a controversy independent of any importance that may attach to the subject of it, are engaged in a disputa. tion upun the question of Peerage Reform. Into the merits of the management of the contest we do not propose to enter; but we may be allowed to say that while the Radical has the advantage of being able to prove that truth and rea- son are on his side of the argument, the Tory shows that he has vast resources at command, in the facility with which he can conceive new fallacies and the ad- mirable ingenuity that characterizes his mode of turning the old ones to account. Whether the fallacy—for so, with all deference, we venture to think it—which we are about to quote, be new or old, we know not ; but taking it as a specimen of the argument in favour of the hereditary legislation doctrine, and the aristo- cracy as it is, advanced, it will he observed, by the most argumentative and in- genious of all its newspaper supporters—looking at in this light, it will be ac- knowledged at once that the fate of the Peers is as good as decided already, that Reform will penetrate even into the House of Lords, and that the Incurables will be cured at last, in spite of themselves. It is asserted with all proper em • phasis, and with considerable composure of countenance, by the advocates of hereditary legislation, than to convert the House of Peers into an elective as- wenshly is neither more ma less than to abolish the Monarchy. destroy. the Church. and (aiming other small inconveniences) subvert the basis of property so as to house a generel confiscation. Leaving the Monarchy and the Church to their (Linger, let us for a moment listen to the heaving% of the foundations of privety shaken and overturned by the introduction of are improving principle 10,0 the Legislature. The coneuessonIN awful ; the ground gi clans beneath ; and eliam comes again, nehered in, like a newly-created Peer, between the Dukes of Devonshire and Bedford. " We do not scruple to sty," say% the Standard, 4. thus a very extensive confiscation of pmperty would be absolutely nemeeary under the new constitution. A Duke of Devonshire, or a Duke of D'Ilf"141. leeked up, as it were, in a House of Lords, is a very harmless pereon ; let him loose, however, with his 200.0001. or 300,0001. a year upon society, by breaking dewn the walls.of the Heuse of Lords, and he will be hartnless no loner. Ile will take.other huie himself. driven by the loss of a legitimate pro- uetion to their wealth, to seek its !security and aggrandizement4 by moans in- consietent with any form cf public liberty. The propmed organic change; un- accompanied by coefiscation, if the thing were possible, would place the ennui y under the meet hideous of all despotiems—the despotism of money." Now we lutist confess diet we were not prepared for any such consequences as this. To us, " melt musing on these matters," the point is new. It is no doubt as novel to al the rest of the world.. Many thousands of persons—we may say manv millione=have by this time accustomed themselves to meditate upon the advantages of reforming the Upper House, and few of us there are who do not fame that the question hits been considered in all ite more impor- tant bearinge. But where is be among the thinking and enlightened host of Peer-Reformers who ever obtained, even in a dream, the most shadowy revela- tion of those :mini consermences which are here contemplated as an inevitable result of the Reform ? Where is iso

" Clamed in with the sea That chides the banks ot England. Wales. or Scotland,"

-whose mind ever hit upon a calculation of the horrors that might ensue from Jetting loose upon society the Dukes of Bedford and Devonshire? It will hardly bear thinking upon, now it has once been thought of! Imagine these two dreadful Dukes—no longer locked up, " as it were," in that eanctuary, a Ihnise of Lords—no longer the " harmless persons" they now are, with no power on earth save that of making laws to which every body. is bound to sub- mit, and of begetting sons, destined to be equally harmless, to protect our chil- dren in the same beneficent manner ; but, instead, let loose upon society !— with two or three hundred thousand a year to take care of, if they can, or, for aught that is known to the contrary, to expend, without scruple, among the various classes of the community. At present, under the eystern which rash Radicals condemn, we lock up these Dukes (as it wert) and others as dan- gerous, in a House of Lords, to save society from the misehievoes influence of their ample fotttmes; we give them the power of inakieg lams, by way of ren- derine them harmless.- This we suspect is, after all, the wise way of dealing with Dukes. Let them legislate, and their power to be mischievons is gone. But under the proposed system (the country will iromtiliately change its mind on this subject), the barrier of safety will be removed with the walls" of the House of Lords," and the effect will be as the throwing open the doom of innumerable Bedlains. We are, however, bound by an instinct of self-preservation, and the necessity of being forearmed against the consequences of any freak that destiny may have in store for us, to endeavour to extract some little hope from the ground overshadowed by this large despair. Supposing we should escape a confiscation, which eve are told is not possible, we are to be placed under " the most hideous of all despotisms, the despotism of money." Here a small ray of light creeps through a cranny of the dark prediction—" a sun-beam that has lost its way." This despotism of money with which we are threatened, cannot surely be very different from the despotism under which we at present exist. If the Dukes of Devonshire and Bedford are to remain for ever locked up in the Home of Lords, and, lest they should employ their vast pecuniary powers to the destruction of the country, invested with the right of making laws for their fellow subjects to whom they are not responsible, then surely we are living under the rule which is deprecated—the despotism of money. Let us look about for another sunbeam. What is the amount of wealth locked up in the House of Lords, compared with that which the present perfection of the consti- tution "lets loose " upon society ? Are the Dukes of Bedford and Devonshire very much richer than certain non-members of that House within whose con- fines alone the said Dukes are harmless? Or do the rich Commoners, and the rich men out of Perliament, seek the "security and aggrandizement of their wealth by means inconsistent with any form of public liberty," because they have not an equal power with the Dukes of Bedford and Devonshire to provide a "legitimate protection" to that wealth ? If it be desirable to render these noblemen "harmless," by conferring upon them the privilege of making Jaws and law-makers, then it should be desirable to increase the num- ber of Peers to a very considerable extent ; to an extent indeed which, in the opinion of some persons, would render any other order of Peerage Reform superfluous, by swamping the Peerage. We should be pro- vided as speedily as possible with a Lord Lewis Lloyd, a Lord Ark- wright, a Lord Crcesus, and a Lord Plutus. It is terrible to reflect upon the harm such men may do, if the Peerage be the only security against the mischievous tendency of wealth. This brings us to the only additional point upon which it is worth while to touch. If there be a mischievous tendency in wealth, its owners [Ring let loose on society, there must be the same mischiev- ous tendency in it, while its owners are locked up, " as it were," in the House of Lords. Were they locked up literally, and compelled to spend their enor- mous incomes within the walls of the sanctuary, the injurious quality of wealth would be neutralized. As it is, the injurious power is equally exercised ; and why should we give additional potency to it by making it a qualification for the Legislature? Why take the dangerous man, and convert him into a law- maker, merely on account of his liability to do mischief? We have done it, it is true. And time it is to ask why?— October 23.

" HARMONIOUS " TORIES: "CENTRIFUGAL" REFORMERS

TIMES—II is vain and ludicrous for the Administration, or their allies of the Destructive Press, to bully away their own fears at the spread of Conservatism through the kingdom. They see in it the death of the Movement to which they both belong. The harmony of the Conservatives utterly confounds them; and it is futile for the motley crew of Papists, Radicals, and corrupted Whigs, to encourage each other by mutual recommendations to cultivate a similar con- cord. The fact is, that the spirit of harmony among the Conservatives requires no cultivation. It is native to the soil. There is amoag them but a single interest,—natnely, the promotion of good government in Church and State; and a single pidicy,—to wit, irreconcileable warfare against those who would de- stroy them both. Whereas the public enemy have in them no element of con- cord. They do not form, like the Conservatives, a national or Engiish party. Party implies a union of individuals or classes for the maintenance of sonic great definite and specific principle, in which they all agree. But what one " principle" binds together the multifarians who compose the present majority in the House of Commons? We cannot say that a ship's company of vaga- bonds, drawn from the dregs of all maritime nations, and with a Red Rover's gag at the mast head, are held together by any common "principle." A com- men object they have, which is spoil, and which affixes to there the name of

than a solitary pledge,--viz. to keep out from administering the affeim of Rag-

land all who aim at a public aud national, as contrasted with a 'Mister and *elfish, end. Anil this le what constitutes the Minieters and their sop- porters an aggregate, not • of. pertiesi but of -factions, each' having its especial game in view, and each working for it alone, even as a pirate for his plunder. What c:ires the Whig, whether the Papist seta up his priest or not, or the Radical his republic, save as one or both may be rendered an instrument of his (the IVIlig's) retention of his salary and his office ? What cares the Redical, whether priest or parent holds the upper hand in Ire.. land, or whether Peel or Russell addresees the Howie of Continues from; ti* Treesury bench, but in so fir as one or the other facilitates the approach of his Republican millennium ? Does the Papist Agitator or Bishop, again, care one pinch of snuff for Peel or Russell, Monarchy or Democracy, or who shall-be King. who President of the Saxon,' here, provided only he shall be himeelf en- abled to trainple on heresy across the Channel, and to riot on the proceeds of lay and ecclesiastical confiscation? We say, therefore, that these three curse pul- ling- and snapping in so many o'ffique directions, are altogether incapable of that one cordial end momentous impulee which springs (loin the nature of Censer. esteem. "Movement" is their watchword ; but for each of them it has a dire. tinet meaning, whitik the others but faintly recognize—a meaning to which self alone is, in every instance, the key. Let us repeat, then, that it is easier foe these variegated politicians to talk about uniformity than to practise it. Their natural tendency is centrifwed : that of the Conservatives is to seek a Common centre, and they find it, as 71ill their forefathers, in Church, State, and Cools tutional Monarchy.— October `23.

RESISTANCE TO UNJUST LAWS.

COURIER—Let it not he said that the Irish are bound to obey the law whee ther it be just or not ; for that would throw them at once helpless on the mercy of their oppressors. In that ease, those who make the law and those who decide when it may he resisted, would- be the amine-persons; and the4rish would be without any redress as long as it pleased • the Tory Peers to oppress them. Suppose the law ordered the Irish Catholic peasants to sacrifice their children, instead of ordering them to give their property to the clergyman: would any man say they ought to obey such a law, or say that they ought net to take into their own halide the responsibility of resisting 'it ? Suppose the Protestant clergy, instead of taking the peasant's potatoes. were authorized by the law to take the peasant himself, and sell him in the.United States or- the West Indies for a slave : would the peasant be bound to subniit to such a law? We answer, no. We say, therefore, that to subjects, at all times, must be left the right of deciding whether they will obey laws or not ; that their decision mew depend on the light in which they regard the law—not on the view taken of it by the law-makers—and on their chance of success, if they decide on te- sisting it. As concerns the Catholic Irish peasantry, there cannot be a shadow of a doubt that the law which takes tithes from them to bestow them on a Pro- testant clergyman, is a most unjust law; neither can there be a duubt that it is grossly offensive to all their feelings. They are no more to blame, therefore, for resisting such a law, than they would be for resisting a law to carry them off to the Colonies., if they can do it successfully. The law is to blame; and those who enaeted, and would not amend it, are the persons against whom a verdict of guilty ought to be brought in. We may remark, in conclusion, that as subjects must in the end be the judges whether they will obey the laws or not,—and from this necessity there is, in a free country, no escaping,—legisla- torsi can only calculate on continued and cheerful obedience as long as they make none but just la:vs. They must make such laws before they can, in conscienee or in reason, ask men to submit to them. —October 28.

BRUTALITY OF GENTLEMEN : FARTIseLITY OF MAGISTERIAL PRACTICE.

TRUE SUN—A respectable middle.aged married woman, the mother of a family, with a young girl in her company, is crossing St. James's Square; when both are laid hold of by four gentlemen, one is thrown down on the pave. anent, the other forced against the railings, the grossest personal indecencies are offered, and resistance calls forth opprobrious language, oaths, and threats of -violence. One of the gentlemen is taken by a Policeman when " applied to ;" two others are recognized sitting at their ease in the Police-office; they give false names, and pay a couple of five- pound fines from a purse which one of them produces, containing several bank.notes. Such a decision is perfect hue punity. There is nut even the check of publicity. The objects of the out- rage are the only persons punished. them falls the disa,greertbleness of hav- ing their real names mixed up with the details of a Police-report. They will probably escape as they can another time, without invoking the equivocal pro- tection of Magisterial law. Nuisances of this species are very common in our streets. They are almost always perpetrated by persons who do not belong to what are called the inferior rails of society. There is probably not a country in the world in which a woinan is so unsafe from insult, if she attempts to go anywhere without a male companion fin. protetion. This disgraceful fact is not a temporary or accidental circumstance. It is an offshoot front the same feudal stock which has to largely blended the feelings of aristocratical insolence, pri- vilege, and licentiousaess, with institutions and manners that have also much in them of a better spitit. The nuiseinees of our streets, the continuous supply of their unhappy population, the degradation of our larger theatres, the annoy- Mums to women, the comparative impunity of insult and violence towards the poor, are all from the source which simples the "jolly full bottle " religion, the bribery of voters, the politics of the pension-list, and the power of inflence in disposing of emoluments in Church and State, the Army, the Navy, and the Colonies. They are adjuncts of a house of hereditary Peers, a law of primogeni- ture, a rich aud lordly hierarchy, and a state of society in which " wealth wakes the man." In one word, they are all ARISTOCRACY, under various modifica- tions or developments. The only efficient check is a large and increasing infusion of the democratic principle. But still the poor palliativee of magistracy and police might be applied less partially. The notorious frequency of a disgusting offence demands proportinnate severity. These finer gentlemen ought all to have been made known. Their names eliould have been pilloried in every newspaper; not that they would have appeared in all, but we sheuld have seen what journals took pay for the suppression, or (which comes to the some thing) depended upon customers who would be offended by this disclosure. A poor culprit never escapes under a false name, though in lli8 case false and true may be just the same to the public. All his aliases and whereabouts are sure to be ferreted out. The brand of a former conviction is as bare upon him as if the iron had burned it into his forehead. But these convicted pseudonymous ruffians may safely mingle with the elite of our vaunted aristocracy ; perhaps say, of its choice coteries, magrat pars fat. Thee will fight the man who tells them they are disgraced, and Inc sure to blackball O'Connell, were he pro. posed for admission into their clubs amongst the "gentlemen of England." A tine of five pounds ! This is like the farce played a fortnight ago with Lord Hill's nephew, who paid ten pounds for stabbing a cabman's horse in the belly, and beating the unoffending driver. He swore; the present culprits only laughed ; but neither the oath nor the laugh provoked that threat of the tread- mill which would have silenced a defendant of a different description. The trouble of signing .a cheque for five or ten pounds of the public money—is that to be called a punishment? It would be more honest at once to vest the class

with the privilege of impunity for their wanton outrages, so long as they exer-

Previous page

Previous page