THE AMAZING POLGARS

Dominic Lawson meets

the first female chess genius in history

GO TO Ladbrokes. Go to William Hill.

Go somewhere, and place a bet that by the end of the century a woman will become

chess champion of the world. The odds should still be long. Up till now such an idea has been entertained only in works of fiction, and the common view has been that of Bobby Fischer, who said that he could train any man ignorant of chess to become as strong as the strongest woman chess player alive.

Bobby Fischer should leave his self- imposed 16-year exile in Pasadena, Cali- fornia and show up at the Eccleston Hotel, near Victoria station in London. Now the Eccleston Hotel is not normally even worth leaving Victoria station for, but this week it is the venue of a new type of chess tournament, pitting a number of women chess players against a collection of young English male chess players and a couple of foreign Grandmasters.

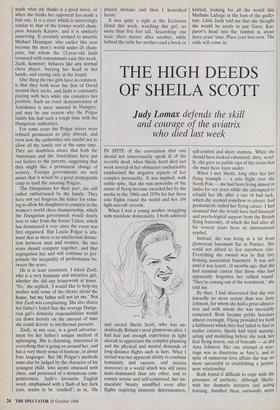

Two of the women are barely women at all, but girls of 12 and 13, the Hungarian sisters Judit and Zsofi Polgar. Zsofi, the older of the two, is merely brilliant. Judit is the most extraordinary phenomenon in the history of chess. She became an Interna- tional Chess Master at the age of 11. No one has been that good that young. Not Kasparov, the current world chess cham- pion, who could not believe it when friends told him the news. Not even Bobby Fischer was that good.

What makes the story still more extraor- dinary is that there is yet another Polgar sister, 19 years old, called Zsuzsa, who is even better, albeit less precocious than Judit. Zsuzsa is the strength of a male grandmaster, and has already defeated players of the calibre of Jonathan Speel- man, Britain's candidate for the male world chess championship and already through to the semi-finals of that event.

Until the arrival of the Polgars no women had broken through into the top 200 in the seeding system which measures the competitive strength of chess players of both sexes. Theses have been written which attempt to find out why it is that women are so bad at chess compared with men. Many have been based on the theory that there is some fundamental difference between the brains of the sexes. But the Polgar phenomenon suggests that those who have argued that the problem for women is merely environmental will now gain the ascendancy in this debate.

For the three sisters are the beneficiaries — or victims — of an educational experi- ment conducted by their own parents, Laszlo and Klara Polgar, both teachers based in Budapest. When I met the mother last, week she herself described the educa- tion of her daughters as an experiment to test a theory of her husband's. If that sounds cold-hearted, it would be mislead- ing. Watching Klara with her daughters, I saw that there was a very close physical and emotional bond between mother and chil- dren. And if she left the playing hall for even a moment, one of her daughters would leap up from the board and run after her, demanding that she stay and watch every move.

The theory of Laszlo Polgar, a teacher in psychology, is first, that children are cap- able of far more learning than conventional educational methods will allow, and second, that to achieve the greatest suc- cess, specialisation should start at a very early age. Zsuzsa herself showed a great interest in chess from the age of four, and passed this fascination on to her younger sisters. From the theoretical point of view it is of some interest that neither the children's parents, nor any other member of the family, living or dead, had shown any great aptitude for chess.

Klara Polgar told me that her husband explained his theory to her before they became married, and told her that their future children would become the experi- ment that would vindicate his theory. None of the children has been sent to school, except for the occasions when they have had to sit exams. It is all rather reminiscent of the story of Ruth Lawrence, the British girl who became an Oxford mathematics undergraduate at the of 12, having been educated entirely at home by her father, a computer consultant.

But chess, the medium chosen by Laszlo Polgar, has several advantages over mathematics as a means of developing and measuring intelligence. It is more creative and subjective. There are no definitively `correct' answers, only different ways of playing. And chess being a professional competitive sport, performance is mea- sured by a seeding system analogous to that in international tennis, which is clearer and more exhaustive than the judgments involved in purely academic assessment.

Klara Polgar insisted to me that her daughters' achievements were purely the results of teaching methods — a diet of five hours of chess a day from the age of four. She insisted that there was nothing intrinsi- cally special about her girls, and that she and her husband could achieve the same results with any averagely intelligent child, if given the raw material at an early enough age. She asks, rhetorically, 'What are the odds against three children — girls -- in the same family becoming chess masters simply through natural ability?'

(The Polgars' methods of producing female chess masters are at least more humane than those of the mother of the reigning women's world chess champion, the Georgian Maia Chiburdanaidze. Maia's mother used to beat her with a metal belt if she lost a game, and so not surprisingly her little girl developed a marked antipathy to losing at chess.) Watching, and talking to the younger Polgar girls last week, my conclusion is that Zsofi is indeed a highly intelligent girl (she speaks English, Russian and Esperanto as well as her native Hungarian) who is playing chess as well as intelligent people can, if trained intensively. But she is no genius at the game, making several un- forced errors in the games I watched.

Judit however is a different matter altogether. For a start she has 'killer' eyes. The irises are a grey so dark they are almost indistinguishable from the pupils. Set against her long red hair, the effect is striking. Judit stares straight into the eyes of her opponent, particularly when she has made what she thinks is a good move, or when she thinks her opponent has made a bad one. It is a stare which is unnervingly similar to that of the former world cham- pion Anatoly Karpov, and it is similarly unnerving. It certainly seemed to unsettle Michael Hennigan, who earlier this year become the men's world under-18 cham- pion, but whom the 12-year-old Judit trounced with consummate ease this week. Zsofi, however, behaves like any normal chess player, burying her head in her hands, and staring only at the board.

One thing the two girls have in common, is that they both wear the Star of David around their necks, and Judit is constantly playing with hers while she considers her position. Such an overt demonstration of Jewishness is most unusual in Hungary, and may be one reason why the Polgar family has had such a tough time with the Hungarian authorities.

For some years the Polgar sisters were refused permission to play abroad, and even now the authorities are careful not to allow all the family out at the same time. They are doubtless aware that both the Americans and the Australians have put out feelers to the parents, suggesting that they might like a permanent change of scenery. Foreign governments are well aware that it would be a great propaganda coup to land the amazing Polgars.

The Hungarians for their part, are still rather embarrassed by the family. They have not yet forgiven the father for refus- ing to allow his daughters to compete in the women's world chess championship, which the Hungarian government would dearly love to take from the Soviet Union, which has dominated it ever since the event was first organised. But Laszlo Polgar is ada- mant that as there is no intellectual distinc- tion between men and women, the two sexes should compete together, and that segregation has and will continue to per- petuate the inequality of performance be- tween the sexes.

He is at least consistent. I asked Zsofi, who is a very feminine and attractive girl, whether she did any housework at home. `No,' she replied, 'I would like to help my mother with some of the chores about the house, but my father will not let me.' Not that Zsofi was complaining. She also shares her father's belief that the average Hunga- rian girl's domestic responsibilities would cut down heavily on the amount of time she could devote to intellectual pursuits.

Zsofi, in any case, is a good advertise- ment for her father's unique method of upbringing. She is charming, interested in everything that is going on around her, and has a very sharp sense of humour, in about four languages. But Mr Polgar's methods must also be judged by the character of his youngest child, who seems obsessed with chess, and possessed of a monstrous com- petitiveness. Judit's favourite English word, emphasised with a flash of her dark eyes, seems to be 'crushed'; as in, 'He played mistake and then I kraarshed heem.'

It was quite a sight at the Eccleston Hotel this week, watching this girl, no more than five feet tall, `kraarshing' one male chess master after another, while behind the table her mother read a book or knitted, looking for all the world like Madame Lafarge at the foot of the guillo- tine. Little Judit told me that she thought she would be ready to put Garry Kas- parov's head into the tumbril in about three years' time. Place your bets now. The odds will come in.

Previous page

Previous page