Exhibitions

John Wonnacott (Marlborough Fine Art, till 18 November) Paula Rego (Serpentine Gallery, till 20 November)

Muddy waters

Giles Auty

While John Wonnacott continues to find visual stimulation in the mud-flats and shoals of the Thames estuary, Paula Rego prefers to trawl for subject matter in the equally murky waters of human psychology and behaviour, often taking childhood memories as a starting point. The two artists are roughly the same age, studied at the Slade and belong to what is often referred to as our mid-generation of pain- ters. Both exhibit through the same com- mercial gallery and are artists of high

technical accomplishment but, in virtually every other respect, could not be more different.

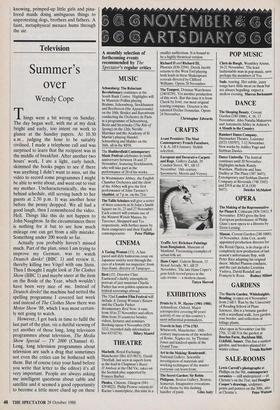

John Wonnacott's paintings at Marl- borough Fine Art (6 Albemarle Street, W1) appear to be essays about the per- ceived world, tackled head-on. Apart from the dozen estuary paintings on view, the artist's massively complex portraits of Sir Adam Thomson, set against aircraft han- John Wonnacott's 'The Hard', 1985-88 gar interiors and a cast of hundreds, show he does not shrink from a challenge. I doubt whether any other artist alive could or would have painted such works. In this artist's case it is hard to say whether the capacity or the compulsion is the more important, yet there is no hint of the virtuoso about Wonnacott. Generally he affects a deadpan and slightly puritanical matter-of-factness, as though to enjoy the sensual potential of paint would be to verge on the sinful. One wonders whether the artist's habitual understatement may not be that most English of ploys intended, simultaneously, to conceal and unnerve.

The genre achieves its apogee in the wartime slang of the RAF pilot: 'Bit of a close shave, what?', as hundredweights of burning metal flash past the cockpit. As an artist, Wonnacott is thoroughly accus- tomed to critical flak; he has passionate supporters but at least an equal number of violent detractors. Why should his innocent-seeming paintings arouse such strong reactions? The artist's approach to the seen is obdurate and uncompromising, making no concessions at all to those 20th-century art movements which are supposed to have changed forever the way in which we perceive the world about us. `The world will never look the same after Picasso/Warhol/Bacon' (or whoever), asserts a succession of intemperate young art critics, but I am afraid that it does — at least to all those countless millions who have failed to read or understand them. John Wonnacott paints the mud-flats of Leigh-on-Sea very much how the casual visitor there might 'see' them, with scores of digging, jumping and sliding children in summertime. The artist uses illusionistic space, complex cloud patterns — usually with vapour trails — shadows, silhouetting and even seagulls unashamedly, ignoring all the inviolable 20th-century formalist conventions as though they had never been stated. The paintings look unedited to the extent that one is not forced to be aware of the editing and decision-making that goes into them. Further, they do not look `artful' either, so that many of their skills and virtues go unnoticed — at least by those who do not understand what a tricky and time-consuming process serious paint- ing can be. To a greater extent than many might realise, I believe Wonnacott's paint- ings are about memory: that of the artist himself, relived now through his children. I spent many of my own childhood summers playing on the mud-flats at Whitstable on the other side of the Thames estuary. While preferring warmer and more exotic locations today, I remember nevertheless how those estuarine sights and smells once thrilled me. Childhood memories remain vivid but one rather hopes that something of significance may happen to us also in adulthood. Perhaps some kind benefactor would arrange now for John Wonnacott to spend some months gazing at the lagoons of the Galapagos, say, or South China Sea?

Paula Rego mines her childhood memor- ies with the assiduity of a forty-niner. Freudian psychoanalysts could have a field-day at the Serpentine. What is the significance of a grim little girl lifting up her skirts before a bored-looking dog? Is this Malice in Wonderland, or something more sinister? I cannot pretend to know, but luckily Germaine Greer explains all in the current issue of Modern Painters. Paula Rego's stunted figures have adult faces and musculature, tacked on to child-sized bodies. Where has one seen such creatures before? In the films of Marcel Came perhaps, or the paintings of Velasquez, Goya and Balthus.

The present exhibition includes work from the early Sixties, from a period when the painter was influenced heavily by the art of Dubuffet, as were many of the time. Few of the early works are of great interest or originality, so giving little hint of the arresting productions to come, notably in the past few years. The artist is Portuguese but trained and has lived much of her life in England. In middle years she has found a rich and unusual vein of imagery, with knowing, primped-up little girls and pina- fored maids doing ambiguous things to unprotesting dogs, brothers and fathers. A faint, metaphysical menace hums through the air.

Previous page

Previous page