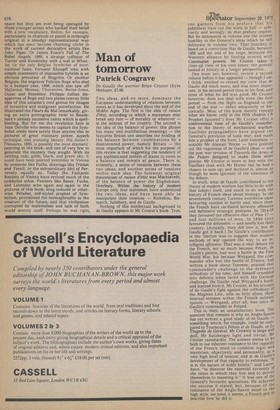

Man of tomorrow

Patrick Cosgrave

De Gaulle the warrior Brian Crozier (Eyre Methuen, E7.00.

Two ideas, and no more, dominate the European understanding of relations between states as it has developed since the end of the Middle Ages. The first is the idea of raison d'etat, according to which a statesman may break any rule — of morality or whatever — in the interest of his country. The second is the idea of the balance of power: this phrase has many and multifarious meanings — the favourite British one describes the holding of the balance between combinations by a disinterested power, namely Britain — the most important of which for the purpose of this review is that suggesting the tendency of any sophisticated system of states to come to a balance and remain at peace. There is, evidently, a series of tensions between these two ideas; and another series of tensions within each idea. The foremost original theoretician of raison d'ectat was Machiavelli; of the balance of power the Englishman, Overbury. Within the history of modern Europe only four statesmen have understood the two ideas, and have been able to manipulate their tensions — Richelieu, Bismarck, Salisbury, and de Gaulle.

Nothing of this intellectual background to de Gaulle appears in Mr Crozier's book. True,

one gathers from his preface that his publishers have cut the work in half — arbitrarily and wrongly, as that preface implies. But he announces in volume one the intense hostility to the General's ideas which he will delineate in volume two. That hostility is based on a conviction that de Gaulle, between 1958 and the end of his reign, betrayed the Western alliance by fooling around with Communist powers. Mr Crozier takes a close-up view of his own times: the general looked at history in a longer perspective. One must not, however, review a second volume before it has appeared — though I am, I think, entitled to record my view that de Gaulle did much more, and was more important, in his second period than in his first; and most of what he did was good. Mr Crozier however, does not deal with even the first period — from the flight to England to the end of the war — either adequately or historically. Most of the book merely repeats what we know: only in the fifth chapter CA Prophet Ignored") does Mr Crozier offer a controversial view of de Gaulle's contribution to the theory of mechanised warfare. Gaulliste propagandists have argued the General's prevision of tank war, and made him a prophet of the form. Later historians — notably Mr Alastair Horne — have pointed out the vagueness of de Gaulle's ideas — and the post war revision of Towards the Army of the Future designed to make them more precise. Mr Crozier is more in line with the Gaullists than with Mr Horne: but he had a chance to sum up; and declined it, almost as though he were ignorant of the existence of the debate.

In truth, what de Gaulle contributed to the theory of modern warfare has little to do with that subject itself, and much to do with the history of French ideas about strategy. In the seventeenth century Turenne overthrew ideas favouring caution in battle and, since then, the French have oscillated between offensive and defensive strategic postures. In 1914-18 they favoured the offensive elan of Plan 17 — and lost millions of men. In 1940 they favoured the defensive — and nearly lost their country. (Actually, they did lose it, but de Gaulle got it back.) De Gaulle's contribution in the 'thirties was to suggest that modern methods of war opened the way to an intelligent offensive. That was a vital debate for the French, not so much because Petain, de Gaulle's patron, had won a battle in the First World War, but because Weygand, the commander who lost the battle of France, had written a book about Turenne, praised that commander's challenge to the defensive orthodoxy of his time, and himself crumbled into defence when faced with the German challenge. De Gaulle read Weygand's book; and learned from it. Mr Crozier, in his account of de Gaulle's fight against the orthodoxy of the Maginot Line, tells us little about these internal stresses within the French military system — Weygand, after all, was once de Gaulle's commander in Poland.

This is, then, an unsatisfactory book. The question that remains is why no Anglo-Saxon has yet written a good study of de Gaulle -something which, for example, could be compared to Tournoux's Fetain et de Gaulle, or Le Tragedie de Gereral. Mr Crawley is large and dull; Mr Sulzberger light and trivial; Mr Crozier ramshackle. The answer seems to lie both in our inherent resistance to the capacitS of the French mind to combine logic and mysticism, objectively and personality, at a very high level of tension; and in de Gaulle's development of that capacity to extremes. "It is in the nature of noble hearts," said Lacordaire, "to discover the essential necessity of the times in which they live and to devote themselves to meeeting it." It was one of the General's favourite quotations. He achieved the success it stated; but, because of tile resistance of the Anglo-Saxon mind to the high style, we need, it seems, a French pen to describe how he did it.

Previous page

Previous page