ITAL Y

Fanfani's Europe

OSBERT HASTINGS' writes front Rome: There is many a gaunt . look and black- framed desperate eye within the huge marble halls of the Italian Foreign Ministry these days. Signor Amintore Fanfani has been back for about four months as Foreign Minister, and, being a vigorous man, has set his customary stiff pace of travel and work. Washington twice; Brussels several times; Mexico; Western Euro- pean Union; the Atlantic Council; talks with the General in Paris; with Couve de Murville here; Wilson; Stewart; off to Norway shortly with the President and then with him to Germany; Brussels again at the start of this week. The question inevitably arises of whetllnr Italy can be expected to transmute all this activity into some fresh effort at shaping European policy which, when all is said and all the travelling done, remains the field where Italian policy can best play a constructive part.

It is firmly on record that the Italians have two principal preoccupations about Europe. The first is to preserve some momentum behind the idea of advancing European political unity. The second has always been to keep open a line to- wards Britain so that London might be offered some sort of relationship with the Six as they approached their own problems of political unity.

Up to the breakdown of the British efforts to

seek entry into the EEC, it was largely accepted in .Rome among sections of political opinion most closely concerned with the thought of a special understanding between London and Rome, that London could never be quite per- suaded of the usefulness of Italian efforts to smooth. the way, that the British quite in- explicably, given their situation, dragged their feet..That has now, of course, been superseded. After, the breakdown there could no longer be any talk of an impending negotiation. The best that the Italians could then do was to spell out their views on paper and devise a set of proposals aimed at pressing ahead with the preparation of greater political unity among the continental Six while taking British interests into account.

These proposals were elaborated . by Signor Giuseppe Saragat when he held the Foreign Ministry before being elected President. They remain the basis of Italian policy in Europe. They called for a meeting of foreign ministers of the Six to clear the ground for a conference of heads of government or heads of state who would draft a declaration on the general lines of European policy. This was to be followed by an experimental period of three years in which the attempt would be made to align foreign and other policies without any formal agree- ment. The European Parliament would be strengthened, and be elected by 'universal suffrage, thus changing its pure)y consultative status. :Britain would be kept informed through the Western European Union.

The Italians worked hard for a meeting of foreign ministers which, if they had hacUbeir way, would have sat last month in Venice. The French turned down the idea. As far as the British position went, the original reply to the Italian proposals was tactful but there was not much doubt that London felt consultation to be not enough; and the news of French obstructive- ness was probably something of a relief. Signor Fanfani had a rather uneasy meeting With the General early last month and came home dissatisfied but at least having avoided any .serious personal quarrel such as the two men have had before.; seemingly he had left the General to talk with the German Chancellor about a foreign ministers' meeting some time, bearing in mind the German elections in the autumn and the General's own reservations. The Italian' hope that the French and Germans be- tween them 'might have been able to produce a clear idea on a specific project—Signor Fanfani is inclined to be a logical man who likes clarity— was of course dashed. The General went to Bonn. The Germans gathered that a meeting of foreign ministers would take place before the end of the year. The French had other ideas. The Italians tried to get the French to elucidate their position. It was much as it had been. earlier.

As for the European Parliament, that has now become caught-up with the Community's dif- ferences on the agricultural fund which are just now due to be faced at Brussels. The Italians are unhappy

about the working of the Community's agricultural arrangements on the grounds, that they are too favourable to the French; they want to talk about the European Parliament and about the beginnings of a Community budget fed from direct sources of income. The French are willing to discuss the first but not at the cost Of having to give their attention to the second and third points. The Dutch are urgently calling for a substantial discussion of all three.

All of which leaves the Italians in a position to which they have grown accustomed; com- pletely opposed to French ideas but going a long

way to try and prevent anti-French feeling from going too far. Bravely talking about evolving 'a common foreign policy among the Six ' when Vietnam and San Domingo have shown more clearly than ever before that even the beginnings of such a thing simply do not exist. A frank acceptance of the fact that the European idea is diminishing in force, 'that it lacks popular drive; the European Common Market would really have arrived, as a Socialist trade unionist said here the other day in a television pro- gramme; when the workers of Fiat, Volkswagen and Renault all go on strike together, like the day in fact when the great Susa came to town.

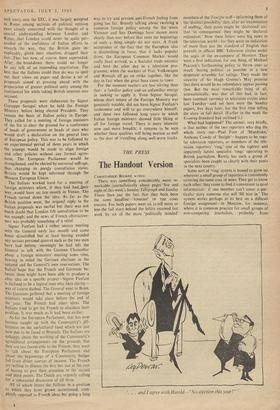

For the moment matters are less stirring than that: a familiar policy and an unfamiliar energy in seeking to apply it. Even Signor. Saragat, whose short•tenure of the Foreign Ministry was genuinely notable, did not have Signor Fanfani's tirelessness and will to go' everywhere himself; .and these two followed long years in which Italian foreign ministers showed little liking at all for foreign travel. There is more intensity now and more breadth; it remains to be seen whether these qualities will bring motion as well as the dust of travelling along well-worn tracks.

Previous page

Previous page