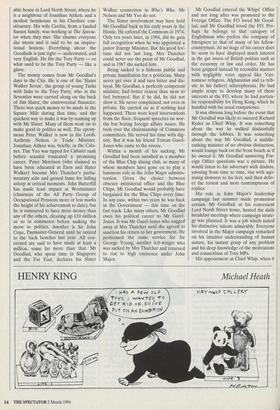

THE PLUMPER, PINKER URQUHART

Mrs Thatcher didn't see the point of him:

everyone else in his Party does — Peter Oborne

offers the first ever profile of Alastair Goodlad

ON MONDAY NIGHT, as John Major and the Government front bench awaited the vote on the Scott report, nobody had more at stake than Alastair Goodlad, the Tory Chief Whip.

The Government faced losing its major- ity; Mr Goodlad faced losing his reputa- tion. Ever since he took over at the Whips' office nine months ago, the Tories have lurched from crisis to crisis, and Mr Goodlad has shouldered the blame.

According to tea-room chat, the Chief Whip should never have permitted the fisheries defeat that sent the Tories into fresh turmoil just before Christmas. He was at fault in allowing John Major to force the vote on the Nolan report that saw the Government plunge to damaging and needless defeat. And his intelligence network should have picked up the calamitous defections of Alan Howarth, Emma Nicholson and Peter Thurnham.

Critics allege that Mr Goodlad is pre- cisely the wrong man to husband the van- ishing Tory majority and maintain the authority of the Government over the Coming months. They say that he is too complacent and remote. There is some speculation that John Major could be forced to step in and remove his trusted Chief Whip in a last attempt to save his administration.

All that is talk. What is undeniable is that it is up to Mr Goodlad, and Mr Goodlad alone, to ensure that the Tories and their vanishing majority can continue in power for the next 12 months and beyond. It is Mr Goodlad who must nego- tiate the late-night deals in smoke-filled rooms with the Ulster Unionists. It is Mr Goodlad who must charm or brutalise skulking Tory MPs into compliance. This Tory Government will stand or fall depending upon whether Mr Goodlad is up to the job. The Chief Whip is a fat, comfortable man with a large pink face. He is often to be seen walking extremely slowly, though with an unmistakable sense of purpose, through the corridors and lobbies of the Commons. He has never been known to panic. His enemies claim that that this is because he is too slow-witted to know when he is in trouble. His friends say that he is very clever indeed. John Major once said that Alastair Goodlad is the `shrewdest man in the Government'.

Mr Goodlad, just like his predecessor John Wakeham, is known as a fixer whose judgment can really be trusted. It was never quite clear what Lord Wakeham had done to deserve his reputation — and the same applies to Mr Goodlad. The politically relevant thing is that it exists. It may have something to do with the Chief Whip being a man of few words. He does not sound off. He never says one word when no words would do. Indeed he rarely says anything at all. Just possibly, this means that others regard him as clev- erer than he really is. At meetings, he sits in a corner looking grave, yawning from time to time and then making a laconic intervention just before the end.

This is all very well, but it means that he is not really a politician in the broader sense of the word. He does not take part in the cut and thrust of national debate. He does not go out and sell the Tory mes- sage. As far as one can tell, he has no deeply rooted beliefs, though he stands on the Left, supports Europe and feels strongly about liberal issues. He voted, for instance, to cut the homosexual age of consent to 16. The Tory Party used to be full of patrician types like Mr Goodlad, shying away from the limelight but at ease — too much at ease, some would say behind the scenes.

He knows all the right people in the Tory Party. Lord Cranborne, the Leader of the House of Lords, is a friend and ally. So are Sir Archibald Hamilton, Lord Hes- keth, William Waldegrave, Tristan Garel- Jones and Douglas Hurd — as well as Jonathan Aitken. If the grandees are real- ly plotting against John Major, as claimed by the Times newspaper, Mr Goodlad would not simply know about it, he would be playing an active part. Mr Goodlad is a member of that small but significant coterie of Tories who believe that Nicholas Soames is as close to physical and moral perfection as a man can get.

Oikish, grammar school types get short- er shrift, and they resent it. Mr Goodlad, before he became Chief Whip, could bare- ly bring himself to acknowledge the exis- tence of the great unwashed of the Tory Party. Even now, he is not seen much in the tea-room, under previous regimes a key point of Whips' office operations. Many MPs complain that he is remote, dif- ficult to approach and almost offensively dull.

But his friends see a different side of the Chief Whip. They speak of his private kindliness, pointing to the fact that John Wakeham was a house guest for three months during his convalescence after the Brighton bomb. They hail him as a witty dinner party companion and a brilliant host. 'I would drop almost anything for the opportunity of lunch or dinner with Alas- tair. He is hilariously funny,' says Lord Cranborne, the Leader of the Lords. There is in restricted circulation a highly competent spoof of Alan Clark's diaries written by Mr Goodlad about a lunch, which he himself did not attend, at Nicholas Soames's flat. It is very funny indeed.

Not that an ounce of grandee blood runs through Mr Goodlad's veins. Educat- ed at Marlborough and Cambridge, his background is emphatically middle-class. His family comes from the Shetlands, and his father was a psychiatrist. He once said that he was brought up in a lunatic asylum, which prepared him perfectly for the House of Commons. His origins are simi- lar to those of, say, Norman Lamont. The difference is that Mr Goodlad, on balance, has made it and Mr Lamont, on balance, has not. Ever since the Cecil's in the 16th century, politics has provided a fast-track route for social advancement. Mr Goodlad is just the latest in a long and, as a whole, illustrious line. Not that he is even faintly vulgar or ostentatious. There is a comfort- able house in Lord North Street, where he is a neighbour of Jonathan Aitken, and a modest farmhouse in his Cheshire con- stituency. His wife Cecilia, from a landed Sussex family, was working at The Specta- tor when they met. She charms everyone she meets and is said to be an inspira- tional hostess. Everything about the Goodlads is just right — understated, and very English. He fits the Tory Party — or what used to be the Tory Party — like a glove.

The money comes from Mr Goodlad's days in the City. He is one of the 'Slater Walker Seven', the group of young Turks with links to the Tory Party, who in the Seventies were carried along on the back of Jim Slater, the controversial financier. There was quick money to be made in the Square Mile during that time, and the quickest way to make it was by teaming up with Mr Slater. Many of them went on to make good in politics as well. The epony- mous Peter Walker is now in the Lords. Anthony Nelson is Trade Minister. Jonathan Aitken was, briefly, in the Cabi- net. Tim Yeo was tipped for Cabinet rank before scandal truncated a promising career. Peter Morrison (who claimed to have been educated at Eton and Slater Walker) became Mrs Thatcher's parlia- mentary aide and gained fame for falling asleep at critical moments. John Butterfill has made least impact at Westminster (chairman of the All Party Group of Occupational Pensions more or less marks the height of his achievement to date), but he is rumoured to have more money than any of the others, cleaning up £10 million or so in commerce before making the move to politics. Another is Sir John Cope, Paymaster-General until he retired to the back benches last year. All con- cerned are said to have made at least a million, some far more than that. Mr Goodlad, who spent time in Singapore and the Far East, declares his Slater Walker connection in Who's Who. Mr Nelson and Mr Yeo do not.

The Slater involvement may have held Mr Goodlad back in his early years in the House. He entered the Commons in 1974. Only ten years later, in 1984, did he gain full recognition when he was appointed a junior Energy Minister. But his good for- tune did not last long. Mrs Thatcher could never see the point of Mr Goodlad, and in 1987 she sacked him.

Being sacked is a hideous public and private humiliation for a politician. Many never get over it and turn bitter and dis- loyal. Mr Goodlad, a perfectly competent minister, had better reason than most to feel betrayed. But if he did, he did not show it. He never complained, not even in private. He carried on as if nothing had happened. There were loyal interventions from the floor, frequent speeches on wor- thy but boring foreign affairs issues. He took over the chairmanship of Commons committees. He served his time with dig- nity. But it was his friend Tristan Garel- Jones who came to the rescue.

Within a month of his sacking, Mr Goodlad had been installed as a member of the Blue Chip dining club, so many of whose members have gone on to play a luminous role in the John Major adminis- tration. Given the choice between obscure ministerial office and the Blue Chips, Mr Goodlad would probably have bargained for the Blue Chips every time. In any case, within two years he was back in the Government — this time on the fast track. Like many others, Mr Goodlad owes his political career to Mr Garel- Jones. It was Mr Garel-Jones who nagged away at Mrs Thatcher until she agreed to sanction his return to her government. He performed the same service for Sir George Young, another left-winger who was sacked by Mrs Thatcher and returned to rise to high eminence under John Major. Mr Goodlad entered the Whips' Office and not long after was promoted to the Foreign Office. The FO loved Mr Good- lad, and Mr Goodlad loved the FO. Per- haps he belongs to that category of Englishman who prefers the company of foreigners to that of many of his fellow- countrymen. At no stage of his career does he seem to have displayed much interest in the gut issues of British politics such as the economy or law and order. He has been gripped instead by recondite matters with negligible voter appeal like Viet- namese refugees, Afghanistan and (a trib- ute to his father) schizophrenia. He had ample scope to develop many of these interests at the FO, where he had particu- lar responsibility for Hong Kong, which he handled with his usual competence.

It was obvious long before the event that Mr Goodlad was likely to succeed Richard Ryder as Chief Whip. It was something about the way he walked disdainfully through the lobbies. It was something about the way Mr Goodlad, a middle- ranking minister of no obvious distinction, would lounge back on the front bench as if he owned it. Mr Goodlad answering For- eign Office questions was a picture. He would listen to his adversary with disdain, yawning from time to time, rise with ago- nising slowness to his feet, and then deliv- er the tersest and most contemptuous of replies.

His role in John Major's leadership campaign last summer made promotion certain. Mr Goodlad, at his convenient Lord North Street home, hosted the daily breakfast meetings where campaign strate- gy was planned. It was a job which suited his distinctive talents admirably. Everyone involved in the Major campaign remarked on his intuitive understanding of human nature, his instant grasp of any problem and his deep knowledge of the motivations and connections of Tory MPs.

His appointment as Chief Whip, when it came, was viewed with deep dismay by the Tory Right, which would have preferred practically any of the other candidates for the job. His friendship with Mr Garel- Jones especially counted against him. There were those who expected him to be an agent of retribution against a Whips' office which, in the view of many, was veering dangerously to the right. Rela- tions between Mr Goodlad's immediate predecessor, Richard Ryder, and the Prime Minister deteriorated badly towards the end. When the Prime Minis- ter called the leadership election, Mr Ryder, to the fury of Downing Street, ordered the Whips to stay neutral. Mr Ryder felt very strongly about this. So did John Major.

His first action on arriving at the Whips' office was to ensure that the staff learnt how to mix a dry Martini. Mr Goodlad is a man who enjoys strong drink, and knows how to hold it too. His next was to set about arranging a series of cracking good parties at the Whips' office headquarters at No. 12 Downing Street. These were presided over with dazzling tact and skill by Mrs Goodlad and deeply appreciated by Tory foot-soldiers who had never been invited inside — for social purposes at least — by Richard Ryder. His third move dispelled any notion that he was the Prime Minister's stooge, gained the approbation of the Right and established him as a pow- erful and independent Chief Whip. Mr Goodlad made plain that the Tory Party in the Commons would never stomach Lord Mackay's Family Homes and `I'm on a Royal Hit-List.'

Domestic Violence Bill, which put unmar- ried couples on the same basis as married people. The Lord Chancellor was forced to withdraw it. Mr Goodlad also tried, with less success, to put a stay on the Lord Chancellor's divorce law reforms. There were those who claimed to detect a change of style between Mr Goodlad and. Richard Ryder. They said that while Mr Ryder merely gave advice to No. 10, Mr Goodlad delivered ultimatums. They accused him of pulling too much weight. They hinted at disloyalty. It was around this time that the first whispers of a grandee plot to put Michael Heseltine in Downing Street, for some reason associat- ed with the name of Sir Archibald Hamil- ton, started to circulate.

There have since been reverses. Mr Goodlad has been blamed for some of them. It is the job of a Chief Whip to take responsibility for mistakes which might otherwise be laid at the door of Downing Street. Perhaps the truth is that no one should be held to account for the series of defeats and defections that have racked the Tory Party since Mr Goodlad took over. It is impossible to tell. Managing the Tory Party is not the simple business it once was. Discipline is more difficult to enforce than ever, following the decision to readmit the nine whipless rebels unchastised and on their own terms.

The Tory Party has been out of touch, arrogant and complacent during the last four years. Mr Goodlad, a respected and influential member of John Major's inner circle throughout that time, was a part of that. He has the presence, the shrewdness and the mystique to make a very fine Chief Whip. He has that necessary touch of Francis Urquhart about him. Behind the comfortable pink face lurks that certain menace that all Chief Whips must possess. (I was the object of a number of civilised threats from interested parties during the research for this profile.) Most crucially of all, he seems to have the total trust of the Prime Minister. If anybody can persuade Mr David Trimble that it is in the interest of the Ulster Unionists to revive their sup- port for this tottering Tory administration, it is surely Mr Goodlad, who saved the Government on Monday without the Unionists' help. Mr Goodlad is one of the most complex and interesting members of John Major's Government. He was born to be Chief Whip.

Peter Obome is assistant editor (politics) of the Sunday Express.

Previous page

Previous page