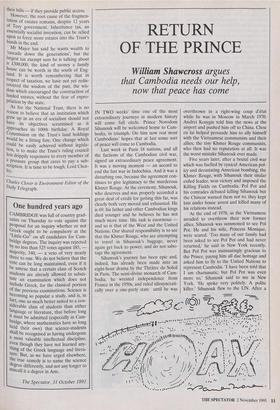

RETURN OF THE PRINCE

William Shawcross argues

that Cambodia needs our help, now that peace has come

IN TWO weeks' time one of the most extraordinary journeys in modern history will come full circle. Prince Norodom Sihanouk will be welcomed home to Cam- bodia, in triumph. On him now rest most Cambodians' hopes that at last some sort of peace will come to Cambodia. Last week in Paris 18 nations, and all the factions of the Cambodian civil war, signed an extraordinary peace agreement. It was a moving moment — an accord to end the last war in Indochina. And it was a disturbing one, because the agreement con- tinues to give legitimacy to the murderous Khmer Rouge. At the ceremony, Sihanouk, who deserves and was properly accorded a great deal of credit for getting this far, was clearly both very moved and exhausted. He is 69, his father and other Cambodian kings died younger and he believes he has not much more time. His task is enormous — and so is that of the West and the United Nations. Our shared responsibility is to see that the Khmer Rouge, who are attempting to travel in Sihanouk's baggage, never again get back to power, and do not sabo- tage the agreement. Sihanouk's journey has been epic and, indeed, has already been made into an eight-hour drama by the Theatre du Soleil in Paris. The semi-divine monarch of Cam- bodia, he wrested independence from France in the 1950s, and ruled idiosyncrati- cally over a one-party state until he was overthrown in a right-wing coup d'etat while he was in Moscow in March 1970. Andrei Kosygin told him the news at the airport and pushed him off to China. Chou en lai helped persuade him to ally himself with the Vietnamese communists and their allies, the tiny Khmer Rouge communists, who then had no reputation at all. It was the worst mistake Sihanouk ever made.

Five years later, after a brutal civil war which was fuelled by cynical American pol- icy and devastating American bombing, the Khmer Rouge, with Sihanouk their titular exiled leader, won victory and imposed the Killing Fields on Cambodia. Pol Pot and his comrades debated killing Sihanouk but the Chinese warned them not to; they kept him under house arrest and killed many of his relations instead.

At the end of 1978, as the Vietnamese invaded to overthrow their now former allies, Sihanouk was summoned to see Pol Pot. He and his wife, Princess Monique, were scared. 'Too many of our family had been asked to see Pol Pot and had never returned,' he said in New York recently. But Pol Pot was insinuatingly gracious to the Prince, paying him all due homage and asked him to fly to the United Nations to represent Cambodia. 'I have been told that I am charismatic, but Pol Pot was even more so,' Sihanouk said to me in New York. 'He spoke very politely. A polite killer.' Sihanouk flew to the UN. After a passionate denunciation of both Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge, he considered defecting, but allowed himself to be per- suaded by the Chinese to fight again — this time against Vietnam.

Vietnam's liberation of Cambodia quickly became an occupation which nei- ther China, nor the nations of Asean, nor the vast majority of the UN, were prepared to accept. (There were clear similarities with the ways the Soviets occupied Eastern Europe after liberating it from the Nazis. Indeed, Vietnamese are about as much loved in Cambodia as are Russians in Poland.) For most of the last decade Sihanouk has been in uneasy coalition with the Khmer Rouge and another non-communist group led by his former prime minister, Son Sann, an honourable but ailing man, against the Vietnamese. While the Chinese have built up the Khmer Rouge, the West has helped their non-communist allies and the British, amongs others, gave them mili- tary training. This policy can be criticised, but its rationale was first to wear down Vietnamese intransigence and second to ensure that not only the Cambodian com- munists (those for and against the Viet- namese) had some strength.

The breakthrough came with the recent rapprochement between Peking and Hanoi, as these two defunct communist regimes decided to prop each other up rather than continue to fight over Cambodia. Last week, Sihanouk gave a superb, virtuoso press conference after the signing in Paris. He said that last summer, 'A Chinese lead- er said to me, "The time has come for peace. We have met with Vietnam to agree to get out of our obligations to the parties in Cambodia." He said, "We want now to give Cambodia to Sihanouk".' And so they did, and in several meetings since last June, Sihanouk by the force of his extraordinary personality has managed to broker the deal by which he is about to return to Cambodia as head of a Supreme National Council which includes Hun Sen, the leader of the People's Republic of Kampuchea, the gov- ernment created by Hanoi in 1979, Son Sann — and the Khmer Rouge.

The difficulties ahead are vast. Every day there are new rows between the vari- ous factions — which Sihanouk often has to settle by threatening to resign. One problem, which he explained in Paris, was where Khmer Rouge leaders like Khieu Samphan, will live when they are in Phnom Penh for meetings of the Supreme Nation- al Council. He explained the problem with his usual humour: `Khieu Samphan has asked me to get permission from Hun Sen for a free inde- pendent zone for the Khmer Rouge. This is a comparison in bad taste — but the Khmer Rouge want a sort of Vatican. Of course, the Pope is absolutely the opposite to the Khmer Rouge, so we are talking about an anti-Vatican for the Red Pope, Khieu Samphan. A little enclave under UN protection. The Khmer Rouge want to avoid demonstrations against them, like there have been in Paris. In Phnom Penh such demonstrations would perhaps be jus- tified.' Pol Pot, who is believed to be still directing the Khmer Rouge and who is unchanged in his ideology, will not be going to Phnom Penh.

Sihanouk will fly back home from Peking accompanied by Hun Sen, the for- mer Khmer Rouge soldier whom the Viet- namese have sustained in office since 1979. The relationship between the two men will be crucial. Sihanouk used to dismiss Hun Sen as a Vietnamese stooge. No longer. He told me recently that, 'I will rely on my lit- tle patriot Hun Sen to keep the Khmer Rouge at bay'.

Hun Seri will now be seen by many Cam- bodians to have the Prince's anointment. He has proclaimed he has renounced com- munism and has embraced liberal democ- racy and has urged the Cambodians to vote for Sihanouk as president of Cambodia. He wants all the Sihanouk magic possible to rub off on him. Sihanouk's own son, Prince Ranaridh, is in charge of Sihanouk's army but he has no real following inside Cambo- dia. Sihanouk might thus decide that Hun Sen would be his most appropriate succes- sor, assuming that they can first be effec- tive partners.

As I have said, Sihanouk's return is only the beginning of the last and nipst difficult stage of his journey. There are those who have denigrated the Paris Peace as a Return to the Killing Fields. That in my view is to scorn the immense work and good faith that the United Nations and

officials of many nations — France, Indonesia, Australia, as well as Vietnam, China, Thailand — have put into it. More seriously, it is to pour ridicule on the hopes of eight million Cambodians, who see this as their best chance of peace.

It is indeed odious that the Khmer Rouge should be allowed back to share power in Phnom Penh. They should instead have been charged with genocide. But no nation was willing to do this. Another truth is that they do have a following amongst the peasantry who have always felt (with good reason) that the corrupt bourgeoisie

has ignored their interests. If the Khmer Rouge had been excluded from any agree- ment, they would have gone on fighting and there would have been no chance of peace whatsoever. Sihanouk and Roland Dumas, the French foreign minister, both made this point very forcefully last week. They will undoubtedly win some seats in an election, particularly if the towns continue to grow much richer and more corrupt as they are already becoming once more.

The problem now is how to implement the ceasefire and the eventual elections. The first United Nations team to go to Phnom Penh will be tiny, quite incapable of enforcing anything. Even when the full UN complement has arrived, there is no way in which it could ever impose a total ceasefire and the disarmament that the agreement envisages.

But it is a start. The good news is that Cambodia is back in the international com- munity. The UN is embarked on the most complicated operation in its history. It is now essential to ensure that the agreement is only a new beginning, not an end, and above all not as an excuse to wash our hands of the country. The UN election plans will cost an enormous amount of money. $2 billion is talked about. Clearing the mines which all sides have laid with careless, ferocious abandon, will be as expensive as it will be difficult. Cambodia needs billions of dollars-worth of recon- struction.

One country which is clearly champing to get into Cambodia is Japan. Indeed, in his speech last week the Japanese foreign minister asserted, rather ominously, 'A new task for all of us is to harvest the fruits of the efforts we all made.' There is no doubt that Japan, along with other nations and great corporations, will try to suck out of the country all its national wealth — teak, gems, fish — and, as with Thailand, fashion it into everything that greedy, blasé tourists demand. On the other hand, a vibrant cash-rich economy, tied into the outside world, is probably the best hope of keeping the Khmer Rouge at bay. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge came to power and stained the Killing Fields red in conditions of autarchy. They must never be allowed that freedom again. A huge foreign presence and dollars in the countryside is the best guarantee against their return. This will mean dragging Cambodia into the toils of 20th-century development. But that IS preferable to the enslavement of mediaeval communist despotism. Sihanouk, who acknowledges his past errors, deserves all support. No one else could have effected the deal in Paris, and that deal offers the best hope of ending the slaughter which has now continued for 21 years — since his overthrow in 1970. No one else has any hope of unifying his coun- try. Now he still needs outside help to drive a final stake through the heart of darkness that is communism in Cambodia. That will be journey's end.

Previous page

Previous page