ARTS

Conservation

Solvent abuse

Michael Daley accuses the National Gallery of continuing damage to its art works in the name of restoration

Late one night in 1970, an elderly man mounted the steps of the portico at the National Gallery and painted 'MURDER- ERS' on the doors. The miscreant was the `society' painter Pietro Annigoni, who 14 years earlier had protested more conven- tionally in a letter to the Times (14 July 1956): A few days ago, at the National Gallery, 1 noticed once more the ever-increasing num- ber of masterpieces ... ruined by excessive cleaning . I do not doubt the meticulous care employed by these renovators, nor their chemical skill, but I am terrified by the con- templation of these qualities in such hands as theirs. The atrocious results reveal an incred- ible absence of sensibility.

The tenacity of these practices was con- firmed recently when a curator from New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art con- demned the 'strident tones' produced by `the exuberant cleaning of paint surfaces for which the National Gallery has, unfor- tunately, become famous'. It is not just artists and curators who are offended — so too are many restorers. Sarah Walden memorably savaged the philosophy in her polemical book The Ravished Image.

The object of the Gallery's notorious and dogmatic insistence on removing every last trace of varnish is to maximise the strength of a painting's colours. But this goal has been thought suspect and dangerous since antiquity. Pliny records the destruction of a painting by Aristides Tebano. The great 17th-century connoisseur Baldinucci recalled how a magnificent painting, when washed, 'crumbled and fell to the ground in minute fragments'. The very desire to `freshen up' colours, Baldinucci saw, is a function of vulgarity and ignorance and, when implemented, robs paintings of beau- ty and historical authenticity. Degas con- curred: 'Time has to take its course with paintings as with everything else, that's the beauty of it.' Goya had warned, 'The more one retouches paintings on the pretext of preserving them, the more they are destroyed.' The original artist, if alive today, could not match, he said, 'the aged tone given the colours by time who is also a painter.'

The National Gallery falsifies the art it seeks to preserve. Stripping paintings down to an alleged 'original' surface does not reveal the painting as it once was but mere- ly exposes the combined injuries suffered and decayings undergone. The original colours and the relationships between them no longer exist. Each colour ages different- ly: some darken, some fade, others remain constant. The removal of all layers of var- nish amplifies the chemically induced dis- cordancy. Such cleaning, therefore, reveals not the 'original' painting but its spruced- up corpse. This tasteless deception is com- pounded by a meticulous filling-in of all the numerous losses and abrasions with fresh, perfectly matching paint. A seamless sur- face of clean, bright colours emerges whose glossy, synthetically varnished 'perfection' creates a plausible but deceiving impres- sion of miraculous recovery.

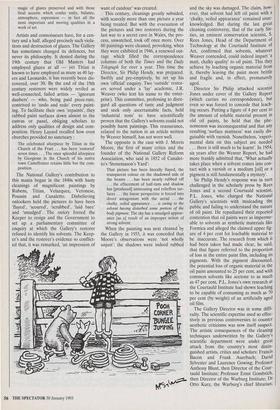

This approach, Annigoni explained, needlessly exposes the painting to assault by solvent and scalpel, jeopardising thereby the very surface as the master left it, aged, alas! as all things age, but with the Before cleaning After cleaning Stone container, right foreground, 'Adoration of the Kings' by Bramantino. Drawing based on photographs published in the National Gallery Technical Bulletin (14) magic of glazes preserved and with those final accents which confer unity, balance, atmosphere, expression — in fact all the most important and moving qualities in a work of art.

Artists and connoisseurs have, for a cen- tury and a half, alleged precisely such viola- tions and destruction of glazes. The Gallery has sometimes changed its defences, but never its philosophy. It denied during the 19th century that Old Masters had employed glazes at all — yet Titian is known to have employed as many as 40 lay- ers and Leonardo, it has recently been dis- covered, over 30. By the end of the 19th century restorers were widely reviled as well-connected, failed artists — 'ignorant daubers' — who, being paid piece-rate, contrived to 'undo and redo' every paint- ing. To facilitate their own 'repaints', they rubbed paint surfaces down almost to the canvas or panel, obliging scholars to address only qualities of design and com- position. Henry Layard recalled how even churches provided no sanctuary : The celebrated altarpiece by Titian in the Church of the Frari . .. has been 'restored' seven times .. . The once splendid altarpiece by Giorgione in the Church of his native town Castelfranco retains little but the com- position.

The National Gallery's contribution to this mania began in the 1840s with hasty cleanings of magnificent paintings by Rubens, Titian, Velazquez, Veronese, Poussin and Canaletto. Disbelieving onlookers held the pictures to have been `flayed', 'scoured', 'scrubbed', 'laid bare' and 'smudged'. The outcry forced the Keeper to resign and the Government to set up a parliamentary committee of enquiry at which the Gallery's restorer refused to identify his solvents. The Keep- er's and the restorer's evidence so conflict- ed that, it was remarked, 'an impression of want of candour' was created.

This century, cleanings greatly subsided, with scarcely more than one picture a year being treated. But with the evacuation of the pictures and two restorers during the last war to a secret cave in Wales, the pro- cess, unwatched, took off once more. Over 60 paintings were cleaned, provoking, when they were exhibited in 1946, a renewed out- rage which filled the correspondence columns of both the Times and the Daily Telegraph for over a year. This time the Director, Sir Philip Hendy, was prepared. Swiftly and pre-emptively, he set up his own 'official' enquiry. Two 'outside' restor- ers served under a 'lay' academic, J.R. Weaver (who lent his name to the enter- prise). This committee, professing to disre- gard all questions of taste and judgment and seek only ascertainable facts, held `industrial tests' to have scientifically proven that the Gallery's solvents could not possibly harm paintings. This reassurance, relayed to the nation in an article written by Weaver himself, has not worn well.

The opposite is the case with J. Morris Moore, the first of many critics and the founder of the National Gallery Reform Association, who said in 1852 of Canalet- to's 'Stonemason's Yard': That picture has been literally flayed, the transparent colour on the shadowed side of the beams .. . has been nearly rubbed off ... the effacement of half-tints and shadow has [produced] unmeaning and reliefless sur- faces .. . the linear perspective is forced into direct antagonism with the aerial . . . the chalky, veiled appearance . . . is owing to the solvent having disturbed some portion of the body pigment. The sky has a smudged appear- ance [as a] result of an improper action of strong solvent.

When the painting was next cleaned by the Gallery in 1955, it was conceded that Moore's observations were 'not wholly unjust': the shadows were indeed rubbed and the sky was damaged. The claim, how- ever, that solvent had left oil paint with a `chalky, veiled appearance' remained unac- knowledged. But during the last great cleaning controversy, that of the early Six- ties, an eminent conservation scientist, S. Rees Jones, Head of the Department of Technology at the Courtauld Institute of Art, confirmed that solvents, whatever Weaver contended, could indeed impart 'a matt, chalky quality' to oil paint. This they achieve by leaching organic material from it, thereby leaving the paint more brittle and fragile and, in effect, prematurely aged.

Director Sir Philip attacked scientist Jones under cover of the Gallery Report (which carries no correspondence), but even so was forced to concede that leach- ing occurs. Putting a figure of 4 per cent to the amount of soluble material present in old oil paints, he held that the phe- nomenon was inconsequential and that any resulting 'surface mattness' was easily dis- guisable with varnish. Nonetheless, 'experi- mental data on this subject are needed . . there is still much to be learnt'. In 1954, six years after the Weaver Report, he had more frankly admitted that, 'What actually takes place when a solvent comes into con- tact with a varnish or a medium [oil] or a pigment is still fundamentally a mystery'.

Sir Philip Hendy's response was in turn challenged in the scholarly press by Rees Jones and a second Courtauld scientist, P.L. Jones, who charged the National Gallery's scientists with misleading the public and failing to understand the nature of oil paint. He repudiated their reported contention that oil paints were as imperme- able to solvents as synthetic materials like Formica and alleged the claimed upper fig- ure of 4 per cent for leachable material to be inaccurate. The research from which it had been taken had made clear, he said, that that figure referred to the proportion of loss in the entire paint film, including its pigments. With the pigment discounted, the potential loss of organic material in the oil paint amounted to 25 per cent, and with common solvents like acetone to as much as 47 per cent. P.L. Jones's own research at the Courtauld Institute had shown leaching to be capable of consuming as much as 70 per cent (by weight) of an artificially aged oil film.

The Gallery Director was in some diffi- culty. The scientific expertise used so effec- tively in previous controversies to counter aesthetic criticisms was now itself suspect. The artistic consequences of the cleaning techniques underwritten by the Gallery's scientific department were under great attack from the country's most distin- guished artists, critics and scholars: Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach; David Sylvester and Laurence Gowing; Professor Anthony Blunt, then Director of the Cour- tauld Institute; Professor Ernst Gombrich, then Director of the Warburg Institute; Dr Otto Kurz, the Warburg's chief librarian; John White, Manchester University's Pro- fessor of Art History. Once again, Sir Philip responded under cover of the Gallery Report, dismissing the charges as Meriting attention only in so far as their authors held prestigious positions. With some triumph he gave his account of events: first, he invited the Gallery's scien- tific adviser to prepare a statement of the claims made by the Gallery's many critics; then he set up inside the Gallery a special committee which included himself, his Keeper and his scientific adviser; and final- ly he invited the scientific adviser to submit his statement to the committee (on which he sat) so that it could, in secret session, evaluate' the Gallery's own formulation of its critics' contentions. They then found 'no valid scientific criticisms of the present National Gallery cleaning policy'. The pre- sent state of scientific understanding as revealed in the technical literature shows the earlier conclusion to have been both complacent and obtuse. Papers delivered at a 1990 Conservation Congress reported variously that:

Cleaning science barely exists . .. Swelling and leaching of moderately aged paints are substantial ... Pigment sensitivity to solvents has been neglected by researchers ... Meth- ods of removing this disfigured [varnish] film are a continuous source of controversy or even polemic ... we may never fully charac- terise or understand the surface of an aged, varnished, grime-laden paint film ... The effect of solvents on paint films is not com- pletely understood ... It is also known that solvents cause oil films to swell. Does the oil film eventually return to its original state or is it permanently changed?

I recently asked the present Director, Neil MacGregor, whether the Gallery is confident that its restorers fully understand the precise nature and extent of the impact their solvents have on paint films being cleaned and whether the Gallery is confi- dent that no leaching of organic material (with consequent embrittlement) has occurred during the last 30 years. I also asked whether any research has been car- ried out on these matters by Gallery staff since the cleaning controversy of the 1960s. Mr MacGregor instructed Dr Nicholas Penny, the Clore Curator of Renaissance Art, to reply on his behalf. He has not responded to these questions.

As it happens, evidence of the scale of solvent-inflicted injury exists in the restora- tion dossiers which the Gallery keeps on every painting. Each dossier is said to con- tain a record of all tests and treatments, scientific analyses, materials deployed (for example, solvents, varnishes, glues), as well as a comprehensive photographic record of treatments. I have asked to see five dossiers and been allowed to see two, 'The Entombment of Christ', attributed to Michelangelo, and 'The Adoration of the Kings' by Bramantino, neither of which contained any technical record of treat- ments. The absence of record of tests on Material removed by cleaning swabs — the only certain method of detecting unwitting removal of pigment — is particularly regrettable. Five requests to see this mate- rial have proved unsuccessful.

In the case of the Michelangelo `Entombment', it has been said that no material now exists other than that pub- lished in the 1970 Report. But that account contained no analysis of material removed from the painting on cleaning swabs and no information on any prior testings of solvent strengths and mixes. It discloses only that `the discoloured varnish was easily removed with the neutral organic solvents customar- ily used for cleaning (in this case a mixture of acetone and white spirit)'. Acetone is the strongest of the commonly used sol- vents and is stronger than neat alcohol. It is know to swell old dry oil paint as well as varnish. The combination of acetone and white spirit swells oil paint more than either substance can in isolation. The more powerful the swelling of paint induced by a solvent, the greater is the quantity of mate- rial leached. Leaching is known to erode the surface of a paint film and to cause embrittlement of its substance. Embrittled glazes are more easily detached from sounder, more elastic underlying paints.

The question of whether pigments or glazes are removed along with varnish is central to all disputes. The Gallery's claim to be able to distinguish between, for example, a brown toning glaze and a super- imposed, browned varnish is not convinc- ing. Restorers recently testing a new cleaning agent were obliged to apply it to the flesh tones and not to the brown back- ground because, even with the aid of a microscope, polarised light and ultra-violet light, 'no visual distinctions were possible, it was difficult to observe the degree of partial cleaning in these dark areas'.

The photographs in both of the two dossiers I have examined indicate solvent- inflicted injuries. One in the 'Entombment' dossier shows the effect of a test patch of solvent on one of the painting's figures. A pencilled note from the restorer, Helmut Ruhemann, observes that 'the cleaned strip here looks more unfinished than the uncleaned parts' — which is true: the cleaned section has a reduced tonal and colour range, not an enhanced one as would be expected with dirt removal. Ruhemann's note continues, 'This effect no longer shows after complete cleaning of the face.' This too was true — after cleaning, the values of the entire face. were reduced to those of the initial test strip. The awk- ward comparison simply ceased to exist as the 'cleaning' progressed.

Permission to publish that photograph here was refused. The Gallery intends to include the photograph in a future exhibi- tion. Nor could any other photograph from the dossier be made available: the Gallery, it was said, permits publication only of those photographs previously published by itself. The photographs in the Bramantino dossier record, among many changes, a clear loss of shading on a pink stone con- tainer in the foreground. When this loss was drawn to the attention of the restorer, she replied:

I agree that the absence of any modelling on

the lower side of the convex curve is odd. It is possible that a red lake glaze has faded. .. . '

The now missing glaze had in fact sur- vived for five centuries prior to the present cleaning during which it disappeared. Pho- tographs taken before and after the clean- ing have been published by the Gallery in the current National Gallery Technical Bulletin. Permission to publish them here was offered on two conditions: that The Spectator be able to assure the Gallery of a sufficiently high standard of photographic reproduction; and that the author of the accompanying article be prepared to sub- mit it to the Gallery for prior approval in order to ensure that, as a press officer put it, 'the photographs are used or interpreted in a way they [the curators] would find acceptable'. When asked whether such a precondition was usual, the officer replied, `Yes, it's the standard thing with particular- ly delicate matters like cleanings.'

The Bramantino cleaning is described in the current National Gallery Technical Bulletin (no 14). The function of these Bul- letins is unclear. In them, the Gallery's restorers describe their own actions and decisions in language which suggests a dis- interested reporting of uncontroversial and verifiable 'facts'. And yet often the content of these accounts is less than complete. The Bramantino report, for example, gives no indication of solvents used and offers no explanation for the altered state of the stone container. A delicate matter indeed.

Michael Daley is the UK director of Artwatch International and is working on a book about recent restorations, to be published by John Murray in June.

Previous page

Previous page