Architecture

The Frank Lloyd Wright Gallery (V & A)

The quality of space

Alan Powers

Can Wisdom be put in a silver rod, or Love in a golden bowl?' Can architecture capture the intangible and hold it — carry- ing it across years and continents? The answer is yes, even if it seldom happens, and then generally after a struggle. The process by which Edgar J. Kaufmann com- missioned an office for his Pittsburgh department store from Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935 had its moments of struggle, entwined with the greater enterprise of building Falling Water, the house poised over a waterfall in a Pennsylvanian wood which sprang Wright back from his trou- bled sixties to the triumphs of his seventies and eighties and put Kaufmann's name into the history of architecture.

Now that the Kaufmann Office has emerged from storage at the V & A and been placed on permanent exhibition as the centrepiece of a Frank Lloyd Wright Gallery in the Henry Cole Wing, a real Wright space has been created, and the effect is electric.

Those who claim that the main point of modern architecture was its command of space, to which the elimination of practi- cality, ornament, custom and tradition needed to be offered as a sacrifice, seldom sound convincing. Only the direct experi- ence of the buildings can put the argument to the test, and this is never as widespread as it should be. Standing at one of the three viewpoints offered of the Kaufmann Office, one is magically transported to the agree- able cigar-smoke feeling of pre-war Ameri- ca. Indeed, the swamp-cypress-veneered plywood covering the floor, walls and ceil- ing enhances the impression of actually being inside a cigar box. Wright called cypress the 'wood eternal', according to his former apprentice Edgar Tafel, quoted in the excellent book The Kaufmann Office by Christopher Wilk (V & A, £14.95) which accompanies the unveiling of the room. Swamp cypress, with typical hyperbole, Wright called 'more eternal'. Although much of the room is very simple, consisting of hardly more than plywood panels and louvres, cutting out any distracting views of downtown Pittsburgh, the selection of each veneer was a lengthy process for the cabinet-maker Manuel Sandoval, who made the room.

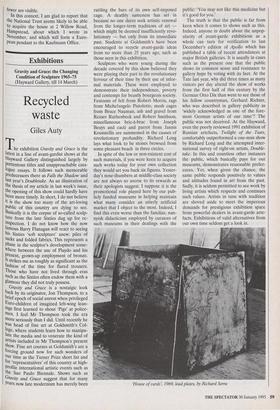

The architectural event of the room is The Edgar J. Kaufmann Office, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright (completed 1937) contained in an alcove on the far side, which due to the low, eight-foot ceiling seems further than it is. A desk, poised to take flight with projecting wings, Is anchored to a wall with a decorative coin- position of more toned cypress based on equilateral triangles, but the way that the ornament grows out of the rest of the room seems to justify Wright's much over-used word 'organic'.

With elaborate and heavy-looking chairs, it cannot have been an easy office to use, although Mr. Kaufmann happily occupied it for 20 years until his death. Yet it cannot have failed to impress his visitors with its unconventional formality, and now it can happily be seen just as a piece of abstract three-dimensional design. The room's effect owes much to the preparation the eye is given in adjusting to its very un- English horizontality, travelling over the wide expanse of the carpet woven by Loja Saarinen to match her yellow and white woollen chair covers.

Thus trained, one can leave this room with a vivid sense of enhanced space, as one may leave an exhibition of paintings with a new sense of colour or line. It is per- haps a platitude to say that we all use space, but few people seem to have a sense of how the spaces between things create their effect. This is particularly noticeable in the continuing reaction against Modern architecture, in which the potential of space tends to be forgotten in a rush to fill emptiness with incident. Buildings current- ly tend to be judged by their level of visible detail, but detail and ornament can fight against the architecture unless the ultimate quality of space is uppermost in the archi- tect's imagination.

The prohibition of ornament typical of Modernism was puritanical and joyless, except when it brought the greater benefit of spatial awareness, which was not often enough. As Wright himself said in a lectute in 1931, 'as many Americans will die of ornaphobia as of ornamentia by the way- side before any goal is reached'. If the Kaufmann Office, with its subtle abstract ornament blending into wood grain, suc- ceeds in re-establishing a balance between space and ornament, it will be richly worth- while and long overdue.

As an example of a museum room, the Kaufmann Office goes against current curatorial orthodoxy. It was donated to the V & A 20 years ago by Edgar Kaufmann Jr when `museology was unknown, but it was a perfect subject for transplantation since it bore little relationship to the building into which it was first inserted. Today, the 'peri- od rooms' of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and other similar collec- tions have become an embarrassment, whether as guilty plunder or under-used space. Even so, there may be an argument for bringing museum 'period rooms' back out of the cold, particularly in relation to the 20th century, from which so few authentic rooms have survived and even fewer are visible.

In this context, I am glad to report that the National Trust seems likely to be able to acquire the house at 2 Willow Road, Hampstead, about which I wrote in November, and which will form a Euro- pean pendant to the Kaufmann Office.

Previous page

Previous page