Exhibitions

Gravity and Grace: the Changing Condition of Sculpture 1965-75 (Hayward Gallery, till 14 March)

Recycled waste

Giles Auty

The exhibition Gravity and Grace is the latest in a line of avant-gardist shows at the Hayward Gallery distinguished largely by portentous titles and unapproachable cata- logue essays. It follows such memorable predecessors there as Falls the Shadow and last year's Doubletake. As an illustration of the thesis of my article in last week's issue, the opening of this show could hardly have been more timely. In short, I do not believe it is the show too many of the art-loving public of this country are dying to see. Basically it is the corpse of so-called sculp- ture from the late Sixties dug up for re- Inspection. I do not know how the now famous Barry Flanagan will react to seeing his Sixties 'soft sculpture' anew: piles of sacks and folded fabrics. This represents a Phase in the sculptor's development some- where between the use of Playdo and his Present, grown-up employment of bronze. It strikes me as roughly as significant as the fashion of the time for flared trousers. Those who have not lived through eras such as the Sixties often endow them with a glamour they did not truly possess.

Gravity and Grace is a nostalgic look back by its originator, Jon Thompson, to a brief epoch of social unrest when privileged E. uro-children of imagined left-wing lean- Rigs first learned to shout 'Pigs' at police- men. I feel Mr Thompson took the era more seriously than I did. Until recently he was head of fine art at Goldsmith's Col- lege, where students learn how to manipu- late the media and to venerate the kind of artists included in Mr Thompson's present show. Fine art courses at Goldsmith's are a forcing ground now for such wonders of our time as the Turner Prize short list and for 'representatives' of this country at high- Profile international artistic events such as the Sao Paulo Biennale. Shows such as Gravity and Grace suggest that for many Years now late modernism has merely been rattling the bars of its own self-imposed cage. A deathly sameness has set in because no one dares seek artistic renewal from the longer-term traditions of art which might be deemed insufficiently revo- lutionary — but only from its immediate past. Students at Goldsmith's have been encouraged to recycle avant-garde ideas from no more than 25 years ago, such as those seen in this exhibition.

Sculptors who were young during the decade covered by this show believed they were playing their part in the revolutionary fervour of their time by their use of infor- mal materials. These were employed to demonstrate their independence, poverty and contempt for beastly bourgeois society. Festoons of felt from Robert Morris, rags from Michelangelo Pistoletto, mesh cages from Bruce Nauman, ash and gravel from Reiner Ruthenbeck and Robert Smithson, miscellaneous bric-a-brac from Joseph Beuys and cacti and parrot from Jannis Kounnellis are summoned in the causes of revolutionary profundity. Richard Long lays what look to be stones browsed from some pleasant beach in three circles.

In spite of the low or non-existent cost of such materials, if you were keen to acquire such works today for your own collection they would set you back six figures. Yester- day's nose-thumbers at middle-class society are not always so averse to its rewards as their apologists suggest. I suppose it is the promotional role played here by our pub- licly funded museums in helping maintain what many consider an utterly artificial market that I object to the most. Indeed, I find this even worse than the familiar, nan- nyish didacticism employed by curators of such museums in their dealings with the public: 'You may not like this medicine but it's good for you.'

The truth is that the public is far from keen when it comes to shows such as this. Indeed, anyone in doubt about the unpop- ularity of avant-garde exhibitions as a whole can turn for verification to last December's edition of Apollo which has published a table of recent attendances at major British galleries. It is usually in cases such as the present one that the public shows its common sense and resistance to gallery hype by voting with its feet. At the Tate last year, why did three times as many visitors per day attend the show of works from the first half of this century by the German Otto Dix than went to see those of his fellow countryman, Gerhard Richter, who was described in gallery publicity as `widely acknowledged as one of the fore- most German artists of our time'? The public was not deceived. At the Hayward, even the poorly reviewed 1991 exhibition of Russian artefacts, Twilight of the Tsars, comfortably outperformed a one-man show by Richard Long and the attempted inter- national survey of right-on artists, Double- take. In this and countless other instances the public, which basically pays for our museums, demonstrates reasonable prefer- ences. Yet, when given the chance, the same public responds positively to values and attitudes found in art from the past. Sadly, it is seldom permitted to see work by living artists which respects and continues such values. Artists in tune with tradition are shoved aside to meet the imperious demands for prestigious exhibition space from powerful dealers in avant-garde arte- facts. Exhibitions of valid alternatives from our own time seldom get a look in.

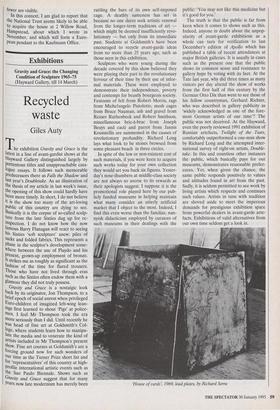

'House of cards', 1969, lead plates, by Richard Serra

Previous page

Previous page