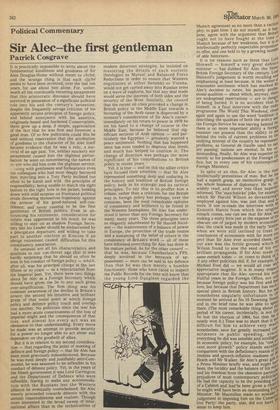

Sir Alec-the first gentleman

Patrick Cosgrave

It is practically impossible to write about the fundamental kindliness and goodness of Sir Alex Douglas-Home without resort to cliche; and the strange thing is that each cliche seems to have been invented, over the last ten years, for use about him alone. For, under neath all the continually recurring amazement that this aristocratic dinosaur should have survived in possession of a significant political role into his and the century's 'seventies; despite the frequently savage criticism of his

apparently arcane principles of foreign policy; and behind annoyance with his assertive, religiously-based and hardened Conservatism, there grew up a deep, if simple, appreciation of the fact that he was first and foremost a good man. Of so few politicians could this be said without reservation that the attribution of goodness to the character of Sir Alec itself became evidence that he was a relic, a survival of an age past. Yet, neither mockery nor amazement caused him the slightest perturbation: he went on remembering the names of ni.-)ple who did him even the slightest service; . -dating with gentleness and forbearance even the colleagues who had most deeply betrayed him: injecting into a Tory Party inclined too often to be harsh and wild the principles of responsibility; being unable to match the right button to the right hole in his jacket; looking down with mild surprise on frustrated political rivals throwing themselves hopelessly against the armour of his good-natured self-confidence; and* never ceasing to be the first gentleman of British politics. Even in announcing his retirement, consideration for others was uppermost in his mind: he was willing to stay on as shadow Foreign Secretary lest his Leader should be embarrassed by a precipitate departure; and willing to take part in another election at Kinross if an abrupt retirement caused difficulties for this constituency association.

So unusual are all his characteristics and qualities in our cut-throat age that it was hardly surprising that he should so often be seen in his conduct of foreign policy — which, after all, was his principal charge in the last fifteen or so years — as a reincarnation from the Imperial past. Yet, there were two things about Sir Alec as a Foreign Secretary which should have given the lie to any such gross over-siinplifcation. The first thing was his constant awareness of the decline in Britain's power; the second his intuitive and brilliant grasp of that nodal point at which foreign policy and defence policy touch and overlap one another. No politician since the war has had a more acute consciousness of the loss of imperial might and the consequences of that loss, and almost his every act was an obeisance to that understanding. Every move he made was an attempt to provide security for a power no longer able to act alone and dependent on the goodwill of allies.

But it is in relation to my second consideration — that regarding the point of meeting of defence and foreign policy — that Sir Alec has been most grievously misunderstood. Because he was most deeply and justifiably anti-Communist, he was assumed to be inflexible in his conduct of detente policy. Yet, in the years of the Heath government it was Lord Carrington and the Department of Defence who were inflexible, fearing to make any accommodation with the Russians lest the Western alliance be eventually overwhelmed. Sir Alec merely proceeded towards detente with the utmost reasonableness and realism. Though more interested in the broad sweep of international affairs than in the technicalities of

modern deterrent strategies, he insisted on mastering the details of such esoteric theologies as Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions in order to ensure that Western negotiators at either Helsinki or Vienna, would not get carried away into Russian arms on a wave of euphoria, but that any deal made would serve the interests of both sides and the security of the West. Similarly, the canard that the recent oil crisis provoked a change in British policy in the Middle East towards a favouring of the Arab cause is disproved by a moment's consideration of Sir Alec's career: immediately on his return to power in 1970 he set his hand to a change of course in the Middle East, because he believed that significant sections of Arab opinion — and particularly the Egyptian — genuinely wanted a peace settlement. Nothing that has happened since has even tended to disprove that thesis, and much has helped to confirm it. The change of direction was perhaps the most significant of his contributions to British policy in recent years. Yet, it is true — and on this the sillier critics have focused their attention — that Sir Alex represented something deep and enduring in the history and tradition of British foreign policy, both in its strategic and its tactical principles. To say this is to proffer him a tribute, rather than a criticism, for the British way in foreign policy has perhaps, over the centuries, been the most remarkable epitome of consistency and brilliance to be found in the Western hemisphere. Sir Alec has understood it better than any Foreign Secretary for many, many years. The three principles once so elegantly adumbrated by Sir Harold Nicolson — the maintenance of a balance of power in Europe, the protection of the trade routes and a sustaining of the belief of others in the consistency of Britain's word — all of these have informed everything Sir Alec has done in his mature period. As for the other canard — that he was, because Chamberlain's PPS, deeply involved in the betrayals of appeasement — more can be said in his defence than that he was then merely a humble functionary: those who have cared to inspect the Public Records for the time will know that the young Lord Dunglass regarded the Munich agreement as no more than a tactical ploy, to gain time. I do not myself, as it har pens, agree with the argument that Britain, ought not to have fought at the time °' Munich because of her weakness, but it i.s,an intellectually perfectly respectable propositil to offer, and one held to by a growing numb° of able historians. It is for reasons such as these that Lord Shinwell — himself a very great defence minister — has dubbed Sir Alec the finest British Foreign Secretary of the century. Lord Shinwell's judgement is worth recalling arld, emphasising at least because, in the welter 0.1 reasonable sentiment which has marked Slr Alec's decision to retire, his purely profes; sional qualities — about which, anyway, ther' are widespread reservations — are in danger of being buried. It is no accident that himself, in a final interview with the radle programme The World This Weekend, cho.se again and again to use the word 'tradition' describing the qualities of both the policy arw the Foreign Service he was leaving behind fr)r there is no more important ability a foreign minister can possess than the ability to see behind the veils of current problems to the. undying interest of the country he represents:. problems, as General de Gaulle used to se!' are passing; nations are eternal. In his tin; derstanding, finally, Sir Alec was superior nr'; merely to his predecessors at the Foreign oi: fice, but to every one of his contempore0 Foreign Ministers. . In spite ot all this, Sir Alec is the least Intellectually pretentious of men. But he has had a superb grasp, an instinctive grasp, °II. the whole business of diplomacy. He is t°,°: widely read, and never less than superbi! informed. The 'matchsticks' joke, for exaMPI,e. which Mr Harold Wilson so devastating0, employed against him, was just that and „nl'r more. If one re-reads the interview with. rgi Kenneth Harris from which the origin°, remark comes, one can see that Sir Alec wa: making a nutty little jest at the expense oft. obscure use of jargon by modern economis.rs, alas, the crack was made in the early ,sixtie,c when we were still inclined to treat ell, conclusions of economists with far more nesc pect than Sir Alec ever accorded them, 3, our awe was the fertile ground which P"r Wilson found to sow the seed of his ev'L, brilliant propaganda. If Sir Alec made tl!t same remark today — or, come to think ef„,,If if any other politician did; if, for example, T Michael Foot did — we would all roar WI appreciative laughter. It is in many respec appropriate that Sir Alec served his 115 fruitful years in the Foreign Office, not ow, because foreign policy was his first and br love, but because that Department has suet' special place in British history. But he Wh9i nonetheless singularly unfortunate in tel moment he arrived at No 10 Downing Streei and in the brief time he was able to sPekrii, there. (The most remarkable thing about period of his career, incidentally, is not th,c he lost the election of 1964, but that he : nearly won it.) Time was so short that it Wri difficult for him to achieve very rnuc,1 nonetheless, save for greatly increased mitments in public spending, alriOnt everything he did was sensible and intelligeer In economic policy, for example, his "one PA cent more growth" policy stands exceliti comparison with the deflationary mania of Jenkins and growth-inflation madness of Heath and Mr Walker. Sir Alec's great glftvf a Prime Minister briefly was, and might 11°4, been, the lucidity and the balance of his 011',01 and his freedom from the obsessive part1c,o,15 prejudices of most contemporary politicla,l'oe He had the capacity to be the presiding glice of a Cabinet and, had he been given a chanyo,

1

Previous page

Previous page