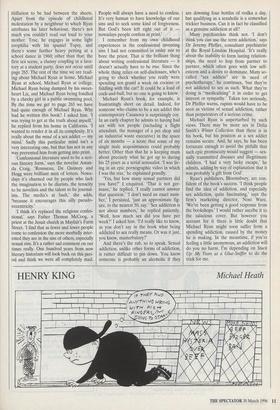

ADMISSION AGE

If we have an addiction which shames us, we now

shamelessly write a book about it, says Isabel Wolff

The Princess of Wales could do so eventually

Ryan's beans-spilling is the latest in a succession of soul-baring books about bad habits. True, there is a long literary tradi- tion of such confessional stuff — Casano- va's Memoirs, Thomas De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater, James Hogg's Confessions of a Justified Sin- ner and Oscar Wilde's De Profundis. But the last few years have seen literary self- disclosure develop into a genre of its own, with writers rushing into print with their darkest and dirtiest secrets. Elizabeth Wurtzel's bestselling Prozac Nation was about the author's dependency on anti- depressants, as was Saint Rachel by Michael Bracewell. Jerry Stahl, an American scriptwriter, relived his heroin addiction in the blackly humorous Permanent Midnight. The Arsenal footballer Paul Merson scored a hat trick by admitting in Rock Bottom that he was a compulsive gambler, drinker and wife-basher. And then there are the celebrity confessions — Back in Business, Michael Banymore's battle with booze and drugs, and Keith Chegwin's account of his alco- holism, Shaken but Not Stirred. Presumably, it is only a matter of time before the Princess of Wales's Down the Toilet: My Battle with Bulimia hits the stands.

For this is the Age of Admission. We can confess our shortcomings shame-free. Political example — the lack of honourable resignations — has shown us how easy it is to escape censure; so we know we risk little when we reveal that we've done something dissolute or dodgy. Moreover, a little judi- cious sinning can be a career move. Why closet your skeletons, when they can be rat- tled for publicity and profit? Bob Hawke set a dangerous precedent when he blubbed on television about his daughter's heroin addiction, only to win the next Aus- tralian general election by a handsome margin. When Paddy Ashdown owned up about his concupiscence, his lower lip may have trembled but his popularity rating soared. The Princess of Wales's televisual confession about her affair with Jamie Hewitt did her no harm at all — indeed her approval rating increased significantly after the Panorama interview.

'I put it down to the Sixties,' says Oliver James, clinical psychologist. 'We've all become much more hedonistic since then, so there's a lot more sympathy for people putting their personal grat- ification before their wider responsibilities.' In any previous era people would have been shunned for parading their peccadil- loes; now they're more likely to get a fat advance and serialisation in a Sun- day newspaper. For the fact is that whereas confes- sional literature used to be a legitimate way of exorcis- ing sins, now it's a means of increasing them, with publishers and features editors tempting us to transgress as often and as interestingly as possible.

'Confessional literature is certainly a big new trend,' says Nicholas Clee of the Bookseller, 'particularly books about addiction. Five years ago you wouldn't have seen this rash of books about dependency. I think people would have found it rather embarrassing. But now it's as though you're not an inter- esting or worthwhile person unless you're in recovery from some kind of abuse.'

'People like the vicarious buzz from reading about other people's bad behaviour,' adds the literary agent Derek Johns. 'There's definitely money to be made with these kinds of books.'

Precisely. Especially if you combine addiction with sex. The problem with Michael Ryan's book is that there isn't much sex. Contrary to the expectations set up by its soft-core cover, there's very little titillation to be had between the sheets. Apart from the episode of childhood molestation by a neighbour to which Ryan attributes his later behaviour, there's not much you couldn't read out loud to your mother. True, he engages in some light zoophilia with his spaniel Topsy, and there's some further heavy petting at a school dance in 1960; other than that; the first sex scene, a clumsy coupling in a lava- tory at a student party, does not occur until page 265. The rest of the time we are read- ing about Michael Ryan at home, Michael Ryan at school, Michael Ryan at college, Michael Ryan being dumped by his sweet- heart Liz, and Michael Ryan being fondled by a cheeky girl in a public swimming pool. By the time we get to page 265 we have had quite enough of Michael Ryan. Why had he written this book? I asked him. 'I was trying to get at the truth about myself,' he replied from his home in California. 'I wanted to render it in all its complexity. It's really about the mind of a sex addict — my mind.' Sadly this particular mind isn't a very interesting one, but that has not in any way prevented him from getting into print. `Confessional literature used to be a seri- ous literary form,' says the novelist Aman- da Craig. 'Rousseau, De Quincey and Hogg were brilliant men of letters. Nowa- days it's churned out by people who lack the imagination to be diarists, the tenacity to be novelists and the talent to be journal- ists. The media's at fault,' she adds, 'because it encourages this silly pseudo- eccentricity.'

'I think it's replaced the religious confes- sional,' says Father Thomas McCoog, a priest at the Jesuit church in Mayfair's Farm Street. 'I find that as fewer and fewer people come to confession the more morbidly inter- ested they are in the sins of others, especially sexual sins. It's a rather sad comment on our times really. One hundred years from now literary historians will look back on this peri- od and think we were all completely mad. People will always have a need to confess. It's very human to have knowledge of our sins and to seek some kind of forgiveness. But God's been left right out of it — nowadays people confess in print.'

I remember from my own childhood experiences in the confessional inventing sins I had not committed in order not to bore the priest. That is the brilliant thing about writing confessional literature — it doesn't actually have to be true. Since the whole thing relies on self-disclosure, who's going to check whether you really were spending ten grand a week on cocaine or fiddling with the cat? It could be a load of cock-and-bull, but no one is going to know.

Michael Ryan's book, for example, is frustratingly short on detail. Indeed, for someone who claims to be a sex addict this contemporary Casanova is surprisingly coy. In an early chapter he admits to having had sex with ten people (including a flight attendant, the manager of a pet shop and an industrial waste executive) in the space of six months — a score that some of my single male acquaintances could probably better. Other than that he is keeping mum about precisely what he got up to during his 25 years as a serial sensualist. 'I was liv- ing in an epic pornographic video in which I was the star,' he explained grandly.

'Yes, but how many sexual partners did you have?' I enquired. 'That is not ger- mane,' he replied, 'I really cannot answer that question.' I don't need an exact num- ber,' I persisted, 'just an approximate fig- ure, to the nearest 50, say.' Sex addiction is not about numbers,' he replied patiently. `Well, how much sex did you have per week?' I asked him. 'I'd really like to know, as you don't say in the book what being addicted to sex really means. Or was it just, you know, masturbatory?'

And there's the rub, so to speak. Sexual addiction, unlike other forms of addiction, is rather difficult to pin down. You know someone is probably an alcoholic if they are downing four bottles of vodka a day, but qualifying as a sexaholic is a somewhat trickier business. Can it in fact be classified as a genuine addiction at all?

Many psychiatrists think not. `I don't think you can use the term addiction,' says Dr Jeremy Pfeffer, consultant psychiatrist at the Royal London Hospital. 'It's really about the inability to form lasting relation- ships, the need to hop from partner to partner, which often goes with low self- esteem and a desire to dominate. Many so- called "sex addicts" are in need of psychotherapy,' he continues, 'but they're not addicted to sex as such. What they're doing is "medicalising" it in order to get interest or sympathy.' Taken too seriously, Dr Pfeffer warns, rapists would have to be seen as victims of sexual addiction, rather than perpetrators of a serious crime.

Michael Ryan is unperturbed by such views. There may be more sex in Delia Smith's Winter Collection than there is in his book, but his position as a sex addict remains secure. And, he says, he has been fortunate enough to avoid the pitfalls that such epic promiscuity would suggest — sex- ually transmitted diseases and illegitimate children. 'I had a very lucky escape,' he admits, adding by way of explanation that it was probably 'a gift from God'.

Ryan's publishers, Bloomsbury, are con- fident of the book's success. 'I think people find the idea of addiction, and especially sex addiction, quite fascinating,' says the firm's marketing director, Noni Ware. 'We've been getting a good response from the bookshops.' I would rather ascribe it to the salacious cover. But however you account for it there is little doubt that Michael Ryan might soon suffer from a spending addiction, caused by the money he is making. In the meantime, if you're feeling a little anonymous, an addiction will do you no harm. I'm depending on Stuck Up: My Years as a Glue-Sniffer to do the trick for me.

Previous page

Previous page