Exhibitions

Van Gogh (Kunstforum, Vienna, till 27 May) Monet (Osterreichische Galerie, till 16 June)

Sombreness and splendour

Martin Bailey

Vienna is now playing host to the megastars of the art world, Monet and van Gogh. With these names, the two exhibi- tions are certain to be blockbusters, but the contrast between them could hardly be greater. Van Gogh concentrates on the work of the young artist, done when he was still under the spell of the sober painters of the Hague School. This was the period when the poverty-stricken Vincent was sketching his lover Sien and beginning his first oil paintings. For most visitors, the Vienna exhibition will come as something of a surprise, revealing a sombre, yet highly personal art, so different from the exuber- antly colourful pictures that followed his move to Paris and Provence. Monet, howev- er, is a retrospective of the painter's entire career — a more predictable extravaganza, culminating in the powerful canvases of his garden at Givenchy.

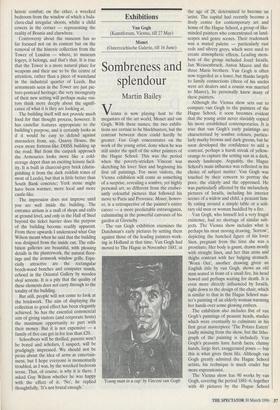

The van Gogh exhibition examines the Dutchman's early pictures by setting them against those of the leading painters work- ing in Holland at that time. Van Gogh had moved to The Hague in November 1881, at 'Young man in a cap' by Vincent van Gogh the age of 28, determined to become an 'artist. The capital had recently become a lively centre for contemporary art and home of the Hague School, a group of like- minded painters who concentrated on land- scapes and genre scenes. Their trademark was a muted palette — particularly rust reds and silvery greys, which were used to create atmospheric effects. Leading mem- bers of the group included Jozef Israels, Jan Weissenbruch, Anton Mauve and the three Mans brothers. Van Gogh is often now regarded as a loner, but thanks largely to family connections (three of his uncles were art dealers and a cousin was married to Mauve), he personally knew many of these painters.

Although the Vienna show sets out to compare van Gogh to the painters of the Hague School, it soon becomes evident that the young artist never slavishly copied his more established contemporaries. It is true that van Gogh's early paintings are characterised by sombre colours, particu- larly murky browns and dark greens, but he soon developed the confidence to add a contrast, perhaps a harsh streak of yellow- orange to capture the setting sun in a dark, moody landscape. Arguably, the Hague School's main influence was reflected in his choice of subject matter. Van Gogh was touched by their concern to portray the poor, the elderly and the oppressed. He was particularly affected by the melancholy pictures of Israels, including his interior scenes of a widow and child, a peasant fam- ily eating around a simple table or a soli- tary old man or woman huddled by a fire.

Van Gogh, who himself led a very frugal existence, had no shortage of similar sub- jects. The Vienna show includes what is perhaps his most moving drawing, 'Sorrow', depicting the hunched figure of his lover Sien, pregnant from the time she was a prostitute. Her body is gaunt, drawn mostly with straight lines, and her thin arms and thighs contrast with her bulging stomach. 'Worn Out', another drawing given an English title by van Gogh, shows an old man seated in front of a small fire, his head bowed and perhaps waiting for death. It is even more directly influenced by Israels, right down to the design of the chair, which is similar to that in the Hague School mas- ter's painting of an elderly woman warming her hands over some glowing embers.

The exhibition also includes five of van Gogh's paintings of peasant heads, studies which were eventually to culminate in his first great masterpiece 'The Potato Eaters' (sadly missing from the show, but the litho- graph of the painting is included). Van Gogh's peasants have harsh faces, clumsy hands, large feet, exaggerated poses — but this is what gives them life. Although van Gogh greatly admired the Hague School artists, his technique is much cruder but more expressionist.

The Vienna show has 90 works by van Gogh, covering the period 1881-6, together with 40 pictures by the Hague School artists. Many of the van Goghs are from private collections and provincial Dutch museums, which means they will be unfa- miliar to most British viewers. The exhibi- tion is particularly rich in drawings and watercolours, works on paper which can only occasionally be exhibited for conserva- tion reasons.

Monet is presented in a palatial setting, the newly renovated rooms of the Upper Belvedere. Just over a hundred works are included, from his schoolboy caricatures to one of his last paintings, 'The Rose Bush', done when he was 85 and almost blind. Selector Stephan Koja says that he deliber- ately avoided 'the most famous pictures', choosing instead what he regards as the best works. Cynics might argue that the well-known masterpieces would have been More difficult to borrow, but the result is livelier with unfamiliar images dotted among the more frequently seen works. One painting, 'The Banks of the Seine' of 1878, is being exhibited for the first time, while others from private collections and Eastern European museums are relatively unknown in the West.

A highlight of the exhibition is the pen- dant to Monet's most famous work, 'Impression, Sunrise', which in 1874 gave its name to the movement. Although the sunrise picture has not come to Vienna, 'Port of Le Havre, Night Effect' is on loan from a private collector. The night-time scene is very sketchily painted, with dabs of bright colours sparingly applied, which must have shocked viewers at the time.

One of the most spectacular rooms in the Vienna show is devoted to Monet's pic- tures of London, painted during his three stays at the Savoy in 1899-1901. In these pictures, Monet depicts light and fog on the Thames, and seeing the works together, as the artist originally intended, heightens the impact. On loan to Vienna are five views of the Houses of Parliament, five of Waterloo Bridge and two of Charing Cross Bridge (sadly none of them is in British col- lections). The exhibition then charts how Monet's work becomes increasingly abstract, partly as a result of his failing eye- sight. This can be seen in his pictures from Giverny, especially in the fascinating con- trast between his 1902 'Garden Alley' and 'The Rose Walk', a similar view done 20 years later. In this later work, the path is just visible, but the swirling rose bushes have become an almost fluid design.

Van Gogh and Monet never met, although Vincent's brother Theo, a Paris art dealer, organised two small Monet exhi- bitions in 1888-9. Vincent greatly appreci- ated Monet's landscapes, which he frequently praised in his letters, and the admiration was mutual. When he saw van Gogh's 'Irises', Monet's response was to ask, 'How could a man who has so loved flowers and light and has rendered them so well, how could he have managed to be so unhappy?' A few months later van Gogh ivas dead.

Previous page

Previous page