SWALLOWED BY THE AMAZON

John Simpson recounts how he almost expired amid the piranhas, jaguars and vampire bats of the Brazilian rain forest

Rio Branco EVERYONE on board our canoe knew that a single misjudgment could capsize us.

But the house-boat which was our base was only half an hour away now, and Claudio, who was young and inexperienced, was keen to show he could do as well as our regular boatman. The rain-forest lay dark and impenetrable on either side of the river, its noises drowned by our out- board motor. Zezinho, whose job was to sit in the bows and shine the torch on the submerged trees and sand- banks which lay in our path, was use- less: he seemed more interested in trying to spot the crocodile-like cay- mans, which the Indians love to eat. When the accident happened, Zezinho screeched liked a frightened macaw, but it was too late: in the darkness Claudio had missed the channel of clear water and steered us right into a couple of large trees which had fallen into the river. Our canoe reared up to the right and stopped, its bows jammed in the branches. The stern slowly filled with water.

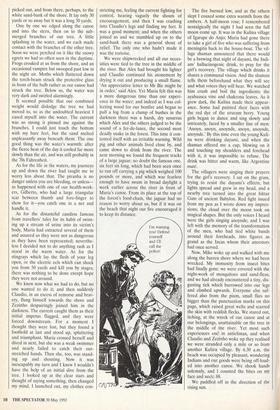

For nine days we had travelled up and down the head-waters of the Envi- ra river, staying in the small villages of Kampa and Kulina Indians along its banks. In Europe the Envira would be one of the longest and broadest of rivers; in Brazil it is just a little known tributary of the Amazon. The most important person in our boat was Maria Bettencour, a farouche and gentle woman in her early thirties, who had chosen to work among the Indians rather than live the well-paid life of a doctor in one of the big cities of eastern Brazil. The Indians treated her like a saint.

Her work is sponsored by a small and highly effective British charity, Health Unlimited, of which I am lucky enough to be a patron. It exists to help the victims of conflict and its aftermath, and operates in the kind of places where few other organi- sations choose to go. The Kampa and Kuli- na may not have suffered from outright war

like the communities in Sudan, Afghanistan, Burma which Health Unlimit- ed sends its teams to, but their way of life, their future and their health are all threat- ened by the destructive advance of the log- gers and miners into the virgin rain-forest. Maria Bettencour's job is to train Indians to be health workers in their own villages, so they .can identify and treat the diseases which poor hygiene or the white man have brought to their areas, chief among them tuberculosis, cholera and measles. By the end of next year, each of the 20 or so Indi- an villages along the 400-mile length of the Envira should have its own trained health worker.

Alex Shankland, Health Unlimited's co- ordinator in Brazil, was with us too: a tall, fair-haired Cambridge man in his 20s, the sort who might well, a few decades ago, have governed a province similar to this in some remote part of empire. Now he was on one of his regular up-country visits, helping to dispense health rather than jus- tice, and being greeted by the tribal chiefs with grave respect. Apart from me the other passenger in the canoe was the photographer Mike Goldwater, an excellent companion.

At first when we hit the tree no one did anything. We were alone in the darkness, in one of the least populat- ed areas on earth, the size of Western Europe. The nearest small town was five days' journey by boat and the for- est was not welcoming. Mike and I had already discussed the possibility of disaster when we first realised Claudio's inadequacies that evening; we had agreed then that Mike should take care of his cameras and film, while I guarded the video-cassettes he had been shooting for me. Now we sat on the upper part of the canoe, gripping our bags like passengers on the Titanic. Things began to slip into the water and disappear: some carved animals for which I had just traded a shirt, a knife, and a BBC pen; my boots, which I just managed to save; Alex's expensive camera; and, sadly, a small tortoise he had been given at the last village.

Everyone behaved remarkably well. Maria was as matter-of-fact as if this often happened to her; Alex and Mike and I spoke in the dialogue of a 1950s British war film; Claudio and Zezinho were too abashed by their

part in the disaster to speak at all.

We decided, if there were time, to tie the important things to the uppermost branches of the tree we had come to grief on: this is the season when the river is at its lowest, so there was no danger that the water-level would rise over-night unless there were heavy rain—and the skies were clear. Our strategy would then be to scram- ble or swim to another fallen tree alongside us, which the feeble beam of our torch had picked out, and from there, perhaps, to the white sand-bank of the shore. It• lay only 30 yards or so away but it was a long 30 yards.

One by one we edged along the canoe and into the stern, then on to the sub- merged branches of our tree. A little splashing in the water, and we each made contact with the branches of the other tree. Soon we were perched on it like the snowy egrets we had so often seen in the daytime. Frogs croaked at us from the shore, and an occasional vampire bat swooped past low in the night air. Moths which fluttered down the torch-beam struck the protective glass in front of the bulb rather as our canoe had struck the tree. Below us, the water was very dark and swirled alarmingly.

It seemed possible that our combined weight would dislodge the tree we had moved to, so as the undoubted heaviest I eased myself into the water. The current was so strong it pinned me against the branches. I could just touch the bottom with my bare feet, but the sand melted unpleasantly away beneath them. The one good thing was the water's warmth: after the fierce heat of the day it cooled far more slowly than the air, and was still probably in the 70s Fahrenheit.

As for the life in the waters, my journeys up and down the river had taught me to worry less about that. The piranha is no danger unless you are bleeding, or unless— as happened with one of our health-work- ers, Gilberto, who had a large triangular scar between thumb and fore-finger to show for it—you catch one in a net and handle it.

As for the distasteful candiou famous from travellers' tales for its habit of swim- ing up a stream of urine into its victim's body, Maria had extracted several of them and assured us they were not as dangerous as they have been represented; neverthe- less I decided not to do anything rash as I stood in the warm water. As for the stingrays which lay the flesh of your leg open, or the electric eels which can shock you from 50 yards and kill you by stages, there was nothing to be done except hope they were not around.

We knew now what we had to do, but no one wanted to do it; and then suddenly Claudio, in an excess of remorse and brav- ery, flung himself towards the shore and Zezinho despairingly joined him in the darkness. The current caught them as their initial impetus flagged, and they were forced downstream. For a moment I thought they were lost, but they found a foothold at last and stood up, spluttering and triumphant. Maria crossed herself and dived in next, but she was a weak swimmer and nearly failed to catch their out- stretched hands. Then she, too, was stand- ing up and shouting. Now it was inescapably my turn and I knew I wouldn't have the help of an initial dive from the tree. I looked up at the clear stars and thought of saying something, then changed my mind. I launched out, my clothes con- stricting me, feeling the current fighting for control, hearing vaguely the shouts of encouragement, and then I was crashing into Claudio's legs and finding my feet. It was a good moment; and when the others joined us and we stumbled up on to the sand-bank there was a general shout of relief. The only one who hadn't made it was the tortoise.

We were shipwrecked and all our neces- sities were tied to the tree in the middle of the river. But Alex had brought his lighter and Claudio continued his atonement by drying it out and producing a small flame. `An appreciative letter to Mr Bic might be in order,' said Alex. Yet Maria felt this was a more dangerous time than our experi- ence in the water; and indeed as I was col- lecting wood for our bonfire and began to pull a log from a clump of bushes in the darkness there was a harsh, dry susurrus which Alex and the others judged to be the sound of a fer-de-lance, the second most deadly snake in the forest. This time it con- tented itself with an irritable warning. Wild pig and other animals lived close by, and came down to drink from the river. The next morning we found the frequent tracks of a large jaguar; no doubt the famous one, six feet six long, which had been seen once to run off carrying a pig which weighed 100 pounds or more, and which was fearless enough to have swum in broad daylight a week earlier across the river in front of Maria's canoe. From its place at the top of the forest's food-chain, the jaguar had no reason to worry about us, but if it was on the beach that night our fire encouraged it to keep its distance.

The fire burned low, and as the others slept I coaxed some extra warmth from the embers. A half-moon rose; I remembered nostalgically the night I had seen .the full moon come up. It was in the Kulina village of Igarape do Anjo; Maria had gone there to take a girl of five who was suffering from meningitis back to the house-boat. The vil- lage shaman announced that there would be a brewing that night of dayami, the Indi- ans' hallucinogenic drink, to pray for the girl's recovery. The village which drinks it shares a communal vision. And the shaman tells them beforehand what they will see and what voices they will hear. We watched him crush and boil the ingredients: the ayahuasca vine and chakrona leaves. As it grew dark, the Kulina made their appear- ance. Some had painted their faces with the red dye of the urucum berry. Young girls began to dance and sing slowly and intricately, faced by a smaller line of men: `Anoyn, anoyn, anoynde, anoyn, anoynde, anoynde.' By this time even the young Kuli- na were drinking dayami, and when the shaman offered me a cup, blowing on it and touching my shoulders and forehead with it, it was impossible to refuse. The drink was bitter and warm, like Argentine

mate.

The villagers were singing their prayers for the girl's recovery. I sat on the grass, trying to resist the dayami's effects; but lights spread and grew in my head, and a nearby tree turned into the great Ishtar Gate of ancient Babylon. Red light issued from my pen as I wrote down my impres- sions; the cloud over the moon took on magical shapes. But the only voices I heard were the girls singing anoynde; and I was left with the memory of the transformation of the men, who had tied white bands around their foreheads, into figures as grand as the Incas whom their ancestors had once served.

Now, Mike woke up and walked with me along the barren shore where we had been wrecked. My immunity from insect bites had finally gone: we were covered with the night-work of mosquitoes and sand-fleas, and we had already encountered a tiny, dis- gusting tick which burrowed into our legs and climbed upwards. Everyone else suf- fered also from the pium, small flies no bigger than the punctuation marks on this page, which raised great welts and scarred the skin with reddish flecks. We stared out, itching, at the wreck of our canoe and at our belongings, unattainable on the tree in the middle of the river. Yet most such experiences end in anticlimax, and when Claudio and Zezinho woke up they realised we were stranded only a mile or so from

another Kulina village. By 6.30 a.m. the beach was occupied by pleasant, wondering Indians and our goods were being off-load- ed into another canoe. We shook hands solemnly, and I counted the bites on my

face and neck: 88.

We paddled off in the direction of the rising sun.

Previous page

Previous page