Eden flies to Paris

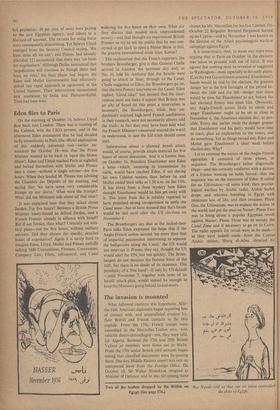

On the morning of October 16, Selwyn Lloyd flew back into London. There was a meeting of the Cabinet, with the C1GS present; and in the afternoon Eden announced that he had decided to fly immediately to Paris (the official explanation of this suddenly advanced visit—earlier an- nounced for October 18—was that the Prime Minister wanted to be back to 'open the Motor Show'). Eden and Lloyd reached Paris at nightfall and locked themselves with Mollet and Pineau into a room—without a single adviser—for five hours. When they landed M. Pineau was advising the Chambre des Deput6s of the meeting, and saying that 'we have some very considerable trumps up our sleeve.' What were the trumps? What did the Ministers talk about all that time?

It was explained later that they talked about Jordan. For five hours? Between a British Prime Minister treaty-bound to defend Jordan, and a French Premier already in alliance with Israel? But if not Jordan, then what? Certainly not mili- tary plans—not for five hours, without military advisers. Did they discuss the specific, detailed issues of negotiation? Again it is surely hard to imagine Eden, Lloyd, Mollet and Pineau usefully talking 1888 Conventions, Firmans, Concessions, Company Law, Pilots, toll-control, and Canal widening for five hours on their own. What did they discuss that needed such unprecedented secrecy—and that brought an experienced British Premier to try to tell his public that he was con- cerned to get back to open a Motor Show in this, the greatest international crisis since Korea?

The explanation that the French reporters, the brothers Bromberger, give is that General Challe arrived in London the previous day and, at No. 10, told Sir Anthony that the Israelis were going to attack in Sinai, through to the Canal. Challe suggested to Eden, the Brombergers go on, that the two Powers intervene on the Canal; Eden replied, 'Good idea!' but insisted that the inter- vention must not make it appear that Britain was an ally of Israel (at this point a reservation is necessary; the Brombergers, while they un- doubtedly enjoyed high-level French confidences in their research, were not necessarily always told the truth : in fact they may have been told what the French Ministers concerned wanted the world to understand, in case the full truth should come out).

Information about a planned Israeli attack would, of course, provide ample material for five hours of secret discussion. And it is known that, on October 16, President Eisenhower sent Eden a letter—which, assuming its transmission by cable, would have reached Eden, if not during his own Cabinet session, then before he and Mollet ended their talks at 1.30 a.m. on the 17th. It has alway been a Suez mystery how Eden thought Eisenhower would let him get away with it. This letter from Ike is reliably reported to have promised strong co-operation to settle the Canal issue—but to have stressed that Ike's hands would be tied until after the US elections on November 6.

The Brombergers say that at the locked-door Paris talks Eden expressed the hope that if the Anglo-French action seemed 'no more than that of impartial peacemaker intervening to separate the belligerents along the Canal,' the US would not interrupt it. Pineau, they say, thought the US would alert the UN, but not quickly. The Brom- bergers do not mention the famous letter of the 16th, but there is no doubt of its existence. This possibility of a 'free hand'—if only by US default —until November 7, together with news of an Israeli attack-plan, would indeed be enough to keep the Ministers going behind locked doors.

Previous page

Previous page