HOW NOT TO INVEST OVERSEAS

By NICHOLAS DAV4NPORT LAST week it was announced in the financial press that one a the big City property companies— City Centre—was going to invest $25 million (nearly £9 million) in a vast skyscraper building which is to be erected over and adjoin- ing the Grand Central railway station in New York. Approval had been given, it was said, by the Treasury and the Bank of England. I could hardly believe my eyes. We have lately been told that capital in- vestment in the private sector of our own economy is not showing much evidence of revival. Manu- facturing industry is even expected to invest less this year than last—in spite of the inducements being offered by the Government to attract manu- facturers to the special areas where unemployment is heaviest. The Board of Trade could surely sug- gest many projects where £9 million could usefully be spent in bringing our manufacturing equip- ment up to date and employing some of our unemployed. Were they consulted before the Treasury and the Bank of England gave permis- sion to City Centre to acquire $25 million for an American building speculation which will not bring one pennyworth of good to our export trades?

It is not as if we have plenty of money to throw across the Atlantic. The Treasury has just had to revise its estimate of the trading surplus on our balance of payments because previously it had greatly exaggerated the earnings of the shipping industry. The new figure for 1958, it says, should be £349 million, not £455 million. And for the first quarter of 1959 the surplus should be £35 million, not £78 million. For the half-year to June 30 we have earned a surplus this year of only £142. million, against £237 million in the first half of 1958. The Treasury is at pains to point out that its revision of our trading surplus does not affect the figures of our gold and foreign currency reserves (which have risen by £77 million in the first nine months of this year), but it cannot go back on what it told the Radcliffe Committee—that the 'desirable' balance-of-payments surplus is an average £450 million a year rather than £300 to £350 million. If our trading surplus is to fall below £300 million this year it is a bad performance and cannot be held to justify sinking $25 million in a New York skyscraper, however profitable it may be to the shareholders of City Centre.

Surely priority in our overseas investment must Still be given to the Commonwealth and par- ticularly to the underdeveloped parts of it? The hand at the Treasury which passed the dollar deal Of City Centre could not have known that 4nother hand was writing in the Treasury Octo- ber Bulletin for Industry this fitting rebuke: 'We have a direct economic interest in maintaining the flow of capital to them [the Commonwealth eountries]. The economic expansion of the less- developed countries is one of the keys to the growth of world trade: and growing oppor- tunities in world markets are what we need in the UK to sustain our own output at a high level and thus raise our own living standards.' For these reasons the Government itself has been ?oing out of its way to provide capital for basic Investment in the sterling Commonwealth which does not yield profit quickly and therefore does 11°1 attract private enterprise. This public invest- Inent inereased•by £35 million to £105 million

in 1958 and reached nearly £64 million in the first half of 1959. Private-enterprise investment in the sterling Commonwealth has been running at around £150 million a year. if the total for public and private investment is now in excess of £200 million a year—over 1 per cent, of the national income—there is surely no margin out of our reduced surplus for luxury investments in American building projects. It seems that the control which the Bank of England and the Treasury are supposed to exercise over capital movements to the dollar area is not being strictly enforced.

This question of control over capital move- ments was fully investigated and discussed by the Radcliffe Committee, which was firmly in favour of its retention. Some witnesses had argued that too much investment overseas was being allowed on the grounds that it was com- petitive with investment at home, which was inadequate. The Radcliffe Committee agreed that it would be foolish to export capital from the UK if that meant denuding British industry and thus impairing its competitive power (p. 740), but it blessed those investments in the Common- wealth and other countries overseas which helped towards an expansion or cheapening of the supplies of import goods and generated addi- tional export opportunities. How can it possibly be argued that the dollar adventure of City Centre satisfies these tests? And if it does not satisfy these tests, why was it allowed? What is the control for if not to disqualify such projects?

There is an additional reason why control of overseas investment in the dollar area should be more strictly enforced than ever before. Notice was given by the American delegates at the recent Washington meetings of the IMF and the World Bank that the United States could no longer be regarded as the universal provider of aid for the underdeveloped countries of the world. It is highly significant that the US Development Loan Fund is to tie its loans in future entirely to American exporters, which should be a lesson for our Bank of England controllers. The protection of the dollar is in future apparently to take priority of foreign aid. This implies that a heavier loan duty will fall on the World Bank, the UK, Ger- many and other creditor nations. No one need object to that, if it is seen that trade follows the loan in the American fashion, but any idea that we have money to spare for investing in dollar skyscrapers when the sterling Common- wealth countries are crying out for development capital can be dismissed as City moonshine. The Treasury approval of the City Centre deal was right off our overseas investment target.

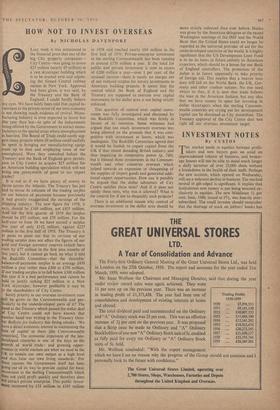

Previous page

Previous page