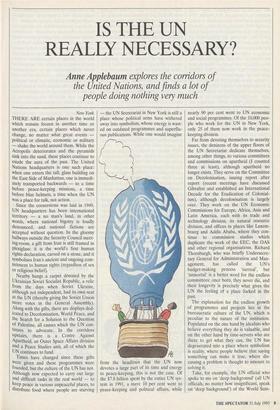

IS THE UN REALLY NECESSARY?

Anne Applebaum explores the corridors of

the United Nations, and finds a lot of people doing nothing very much

New York THERE ARE certain places in the world which remain frozen in another time or another era, certain places which never change, no matter what great events political or climatic, economic or military — shake the world around them. While the Acropolis deteriorates and the pyramids sink into the sand, these places continue to exude the aura of the past. The United Nations headquarters is one such place: when one enters the tall, glass building on the East Side of Manhattan, one is immedi- ately transported backwards — to a time before peace-keeping missions, a time before blue helmets, a time when the UN was a place for talk, not action.

Since the cornerstone was laid in 1949, UN headquarters has been international territory — a no man's land, in other words, where national bigotry is loudly denounced, and national fictions are accepted without question. In the gloomy hallways outside the Security Council meet- ing-room, a gift from Iran is still framed in plexiglass: it is the world's first human rights declaration, carved on a stone, and it symbolises Iran's ancient and ongoing com- mitment to human rights (regardless of sex or religious belief).

Nearby hangs a carpet donated by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, a relic from the days when Soviet Ukraine, although not independent, had its own seat at the UN (thereby giving the Soviet Union more votes in the General Assembly). Along with the gifts, there are displays ded- icated to Decolonisation, World Peace, and the Search for a Solution to the Question of Palestine, all causes which the UN con- tinues to advocate. In the corridors upstairs, there is a Centre Against Apartheid, an Outer Space Affairs division and a Peace Studies unit, all of which the UN continues to fund.

Times have changed since these gifts were given and these programmes were founded, but the culture of the UN has not. Although now expected to carry out large and difficult tasks in the real world — to keep peace in various unpeaceful places, to distribute food where people are starving

— the UN Secretariat in New York is still a place whose political arms have withered away into symbolism, whose energy is wast- ed on outdated programmes and superflu- ous publications. While one would imagine from the headlines that the UN now devotes a large part of its time and energy to peace-keeping, this is not the case. Of the $7.8 billion spent by the entire UN sys- tem in 1991, a mere 10 per cent went to peace-keeping and political affairs, while nearly 90 per cent went to UN economic and social programmes. Of the 10,000 peo- ple who work for the UN in New York, only 25 of them now work in the peace- keeping division.

Far from devoting themselves to security issues, the denizens of the upper floors of the UN Secretariat dedicate themselves, among other things, to various committees and commissions on apartheid (I counted three at least), although apartheid no longer exists. They serve on the Committee on Decolonisation, issuing report after report (recent meetings have discussed Gibraltar and established an International Decade for the Eradication of Colonial- ism), although decolonisation is largely over. They work on the UN Economic Commissions for Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America, each with its trade and technology division, its natural resource division, and offices in places like Luxem- bourg and Addis Ababa, where they con- tinue to commission studies which duplicate the work of the EEC, the OAS and other regional organisations. Richard Thornburgh, who was briefly Undersecre- tary General for Administration and Man- agement, has called the UN's budget-making process 'surreal', but `immortal' is a better word for the endless committees: once born, they never die, and their longevity is precisely what gives the UN the feeling of a place locked in the past.

The explanation for the endless growth of programmes and projects lies in the bureaucratic culture of the UN, which is peculiar to the nature of the institution. Populated on the one hand by idealists who believe everything they do is valuable, and on the other hand by time-servers who are there to get what they can, the UN has degenerated into a place where symbolism is reality, where people believe that saying something can make it true, where dis- cussing a problem is thought to amount to solving it.

Take, for example, the UN official who spoke to me on 'deep background' (all UN officials, no matter how insignificant, speak on 'deep background') of the World Sum-

mit for Social Development. The Social Summit, as it is known in UNspeak, is a conference of world leaders which is sched- uled for 1995. Although it is being planned along the lines of the Environmental Sum- mit in Rio, its goals, the official said, are much broader: the elimination of poverty, the reduction of unemployment and the ending of social disintegration — 'or rather the beginning of social integration, we like to accentuate the positive'. That means, apparently, that minorities like women must 'have a voice' too.

Within the world as UN bureaucrats see it, events like the Social Summit are not just optional icing tacked on to the political cake: they are the substance of politics itself. 'Talking about these problems will help solve them,' this particular official told me, 'we need to put these issues back on the international agenda,' meaning, pre- sumably, the UN agenda, since she knows no other. This is, after all, a woman who joined the UN over ten years ago, will probably never be made redundant, will almost certainly be promoted: it is in her interests to have as many conferences as possible. This is a woman who also com- plains that her department is understaffed, which is probably true. Due to budgetary strains, the UN has had a hiring freeze for the past year. Like everyone else who works at the Secretariat, she also grumbles about 'certain big countries' not paying their dues, which is not as true as she thinks. In fact, member states paid nearly 94 per cent ($976 million out of $1.04 bil- lion) of last year's regular budget, discount- ing peace-keeping and other agencies.

She is correct in saying that the UN is plagued by a perpetual financial crisis, however, although she does not make the connection between wasteful projects like the Social Summit and the need for budget cuts. In fact, the Social Summit — along with the Global Conference on Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States, the World Conference on Natural Disaster Reduction, and the Ninth UN Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders — is one of nine international conferences which the UN is sponsoring over the next three years.

Each one of these needs publicity, advance planning, and a secretariat (with offices and computers) to organise it. Each one requires international travel — a senior UN executive flies first-class and receives up to $300 per day expenses and each one forces government officials to take time away from other duties. Some, like the Fourth Conference on Women, are follow-up conferences which will require further follow-ups; others are simply gifts given to small countries which could use the extra hard currency. While it is true that these conferences do not take up a huge proportion of the UN budget, it is fair to say that the budget targets would be eas- ier to meet without them.

UN waste, of course, has not escaped everyone's attention, and the nine confer- ences are not the only example of it. Reform is a constant topic among the UN's top bureaucrats, 'efficiency' and 'manage- ment skills' are the new buzz words. Yet from year to year, little seems to change. According to one western diplomat, Secre- tary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali has found himself unable to fulfill promises of staff reductions, and has therefore refused to publish an official staff list for the past two years. 'I find myself counting names in the phone book when I want to know how many people work here,' she complained. The member states themselves made one recent attempt at restructuring the General Assembly. It collapsed at the end of June, partly because no one could agree on how many seats of a particular committee should be given to developing countries.

It is true that the UN has an auditing sys- tem and a budgetary oversight committee (whose members also speak only on 'deep background'), but these bodies look for corruption and waste within departments which have already been set up, and do not ask, say, whether an international confer- ence is required to solve the problem of social disintegration. In a bureaucracy which is responsible to everyone and no one, even press scrutiny has little impact. Last year, the Washington Post pointed out that the UN Centre on Transnational Cor- porations had spent 15 years drafting a `code of conduct' for multi-nationals invest- ing in developing countries (for 'code of conduct' read 'restrictions on foreign investment'), at a yearly budget of $6.4 mil- lion. To date, that centre has yet to be dis- solved.

As for individuals who try to reform the system from within, they risk ostracism and loss of their jobs. In an office building not far from the Secretariat, I met a UN offi- cial who had been hired from the private sector in order to bring management tech- niques to a particular department. After a year in the job (during which time he rec- ommended more management training for UN employees and merit-linked promo- tion, among other things) he found himself accused of racism: calling for higher stan- dards, apparently, was tantamount to dis- crimination against employees from developing countries. The director of the department apologised, and transferred the man to a lower-level job. Alas, he too spoke on 'deep background', and would not be quoted by name.

For too many UN bureaucrats from poor countries, a New York posting is not a job but a reward for good service, something they feel they deserve; for too many others, it is a place to go when one's party falls out of power or one's leader falls from grace. For some, it is even a frightening experi- ence. After all, bureaucrats hint, the ex- communist countries once filled their bureaucratic quotas with KGB operatives — few of whom have seen fit to retire. Much weirder are the stories about Sri Chinmoy, a guru who conducts readings and meditation sessions inside the UN building, and has allegedly organised many mid-level bureaucrats into a secret brother- hood within the UN.

Now, there is nothing so terrible about gurus, and it even makes sense that lonely people living in a foreign city band together for company. But the UN is a secretive place, the kind of place where even the simplest piece of information is hard to elicit. I went, for example, to four depart- ments to find out the cost of the Social Summit. One told me the information was unavailable for 'security reasons', another said that it was 'impossible to know at this time'. A third told me to send a fax which would be forwarded to someone in Vienna (whose phone number could not be revealed). Only the fourth, the press secre- tary of the Chilean ambassador — who is not a UN employee — would tell me that the UN has put up,$2.5 million for start-up costs. In that atmosphere, it is no wonder that rumours of gurus and organised cabals seem oddly terrifying: one never knows what anyone is really up to.

Of course none of the problems described here — nor the secretiveness, the resistance to reform, the weirdness or the waste — is very new. As long ago as the early 1980s, Jeanne Kirkpatrick, the Ameri- can ambassador to the UN, described the organisation as nothing more than a place for nations to let off rhetorical steam. She called this the 'Turkish bath syndrome'.

Since 1989, however, the 'international Community' (Britain, America, France, and Russia, that is, with China abstaining) has been gripped by collective amnesia where the UN is concerned. Long reviled as a `talking shop', the UN was suddenly called upon to perform incredible tasks. The same bureaucrats who were considered incompe- tent in the past were immediately asked to organise food and weapons for armies in Bosnia, Cambodia, Somalia. The same institution which had always been described as corrupt and ill-managed was asked to make difficult military decisions at very short notice. And yet the world is sur- prised when the UN reveals, as it did last week, that eight top officials involved in the Cambodian peace force have been sus- pended for corruption, or that commanders in Somalia disagree about tactics, or that some of the UN battalions in Croatia arrived without weapons, training or any clear idea of what they were supposed to be doing there.

In fact, many of the problems which have appeared abroad merely reflect difficulties which have always plagued the UN's New York headquarters. Thanks to poor organi- sation, for example, the Department of Peace-keeping Operations and the Field Operations Division report to different authorities: when the two units disagreed in Cambodia, no one ranked lower than the Secretary-General himself had the authori- ty to reconcile them. Thanks to lack of trained staff, the UN military operation in Somalia was called 'essentially dysfunction- al' in a report prepared for the American Senate. It would have failed entirely with- out American administrative support.

Given the UN's institutional flaws, the failures of recent peace-keeping efforts are not extraordinary: what is extraordinary is that anyone ever thought they would work in the first place. Leaving aside the fact that the UN is not, as many pretend, a sovereign state which can command sol- diers and expect them to obey, it was sim- ply unfair to ask the institution to carry out the tasks now required of it. At the end of 1991, the UN peace-keeping budget was $700 million and the number of peace- keepers, soldiers and civilians hovered around 11,000. Now, the costs are closer to $3.5 billion, and the number of peace-keep- ers around the world has soared to 90,000. Giving huge new projects to an old-fash- ioned, unreformed bureaucracy was always going to be a recipe for disaster.

This is not to say that the UN needs vast new resources, as Boutros-Ghali has claimed. It only took three people to nego- tiate the recent cease-fire in El Salvador, the UN's most successful recent project. But if we want the UN to continue sending blue-helmeted policemen into far-flung parts of the world, the institution itself needs reform. Many of the UN funding agencies have proved their worth in the past, but do we still need a UN Committee on Trade and Development, or a UN uni- versity in Tokyo, or a Social Summit?

If efficient policing is what we now expect the UN to provide, better to dis- band these projects immediately and spend the same time and the same money build- ing a serious international police force from scratch, with its own supply systems, its own intelligence networks, and its own training schemes. If peace-making is what we want the UN to occupy itself with, we should place a moratorium on pointless economic studies, and hire 15 well-paid professional negotiators instead. Simply attaching expensive new departments to the existing organisation will produce more of the problems we have now, and will not cure the institution of its fundamental bureaucratic ills.

Most of all, western politicians should not continue to speak of 'breathing life' into the UN. For the UN is not a 'dead' organisation; we only thought it was dead because we were not interested in its fate. In fact, it has been alive and even growing for a long time — living and breathing according to the fashions of another age.

Previous page

Previous page