THE KINGDOM OF TAMBURLAINE

Stephen Handelman on

the nationalist sensibilities of Soviet Central Asia

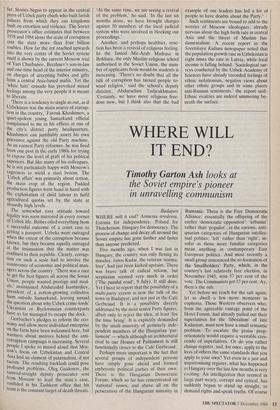

Samarkand IT IS only a short walk from the green marble tomb of Tamburlaine, the 14th- century conqueror of Central Asia, to the Soviet Intourist hotel in Samarkand. The passage has a certain historical irony: what Tamburlaine accomplished with the sword is still beyond the reach of his imperial imitators five centuries later. 'Are you Russian?' I innocently asked a group of children who latched onto me as I made my way back to the hotel. 'No,' came the unequivocal reply.

Under the imperatives of political geography, the vast desert plain stretching from the Aral Sea to the mountains of Afghanistan is known as Soviet Central Asia. But this is stretching a point. Moscow-style boulevards and buildings have indeed replaced most of the winding alleys and obliterated much of the exotic mystery of Tashkent, Samarkand and Bokhara. However, as you probe further, there is distinctly less Soviet and more Asiatic influence. At the hotel for dinner, when I asked a waiter whether there was a table free, he tossed me a mischievous grin and said, 'Of course, this is communism.'

Mr Gorbachev, his hands already full this month with nationalist unrest in the Baltic and the Caucasus, can be grateful that Tamburlaine is safely in his tomb. In fact, it can be assumed that one important reason Moscow remains obdurate in refus-

ing to grant Estonians, Armenians and their comrades-in-arms the additional autonomy they seek is the explosive effect such a decision is liable to have on the peoples and nationalities in the most un- assimilated part of the Soviet Empire. Even a brief sojourn in Soviet Central Asia turns up horrified comments from local officials about what would happen if things were allowed to get as far as they have in Tallinn and Tblisi. Central Asian politi- cians are in the forefront of efforts to defuse the current constitutional crisis.

A deceptive calm now fills the region. No one is marching through the streets or spearheading petition drives to the Krem- lin, yet there are signs of growing resent- ment of Moscow. The trigger, oddly enough, is Moscow's attempt to clean up political corruption in Uzbekistan, the wealthiest of the central Asian Republics. At least 100 of Uzbekistan's leading party officials have been charged with taking bribes. Some 3,000 apparatchiks have lost their jobs and more than 18,000 Commun- ist Party members have been expelled. The anti-corruption drive began in 1983, but it did not really pick up steam until Mr Gorbachev came to power two years later with a self-assumed mandate to lead the country out of the 'stagnation period' — the coded description of his predecessor Leonid Brezhnev's reign.

Few doubted that things had gone too far. Stories began to appear in the central press of Uzbek party chiefs who built lavish palaces from which they ran kingdoms built on extortion and violence. The Soviet prosecutor's office estimates that between 1978 and 1984 alone the scale of corruption cost the state more than four billion roubles. How far the rot reached upwards into the very centre of the Soviet system itself is shown by the current Moscow trial of Yuri Churbanov, Brezhnev's son-in-law and one-time head of the interior ministry, on charges of accepting bribes and gifts from a central Asia-based mafia. Yet the 'white hats' crusade has provoked mixed feelings among the very people it is meant to liberate.

'There is a tendency to single us out, as if Uzbekistan was the main source of corrup- tion in the country,' Farouk Khashimov, a quiet-spoken young Samarkand official complained to me in his offices at one of the city's district party headquarters. Khashimov can justifiably assert his own grievance against the old Party machine. As an earnest Party reformer, he was fired from one post in the early 1980s for trying to expose the level of graft of his political superiors. But like many of his colleagues, he is not particularly happy with Moscow's eagerness to wield a steel broom. The 'Uzbek affair' was primarily about cotton, the main crop of the region. Padded production figures went hand in hand with the exploitation of child labour to fulfil agricultural quotas set by the state at absurdly high levels. The somewhat easy attitude toward legality was soon mirrored in every corner of Uzbek life. Bribes oiled everything from a successful outcome of a court case to getting a passport. Uzbeks were outraged When the extent of the corruption became known, but they became equally outraged at the insinuation that the matter was confined to their republic. Clearly, corrup- tion on such a scale had to involve the connivance of economic and political man- agers across the country. 'There was a race to get the best figures all across the Soviet Union, people wanted 'prestige and med- als,' maintained Abdurashid Isanturdiev, President of a cotton-growing collective farm outside Samarkand, leaving unsaid the question about why Uzbek crime-lords' Ukrainian or Byelorussian counterparts have so far managed to escape the dock. Gorbachev's pledges to reform the eco- nomy and allow more individual enterprise on the farm have been welcomed here, but wariness about motives behind the anti- corruption campaign is increasing. Several People I spoke to mused aloud that Mos- cow's focus on Uzbekistan and Central Asia had an element of paternalism, if not racism. The resulting backlash could pose Profound problems. Oleg Gaidonov, the ramrod-straight deputy prosecutor sent from Moscow to lead the state's case, confided in his Tashkent office that his team is the constant target of death threats. 'At the same time, we are seeing a revival of the problem,' he said. 'In the last six months alone, we have brought charges against 50 members of the local judicial system who were involved in blocking our proceedings.'

Another, and perhaps healthier, reac- tion has been a revival of religious feeling. In the famed Mir-Arab Madrasa in Bokhara, the only Muslim religious school authorised in the Soviet Union, the num- ber of applicants from would-be students is increasing. 'There's no doubt that all the talk of corruption has turned people to- ward religion,' said the school's deputy director, Abdurachim Tadjeakhmatov. 'Certainly, we have more religious free- dom now, but I think also that the bad example of our leaders has led a lot of people to have doubts about the Party.'

Such sentiments are bound to add to the worries of Moscow ideologues, already nervous about the high birth rate in central Asia and the threat of Muslim fun- damentalism. A recent report in the Sovetskaya Kultura newspaper noted that the population growth rate in Uzbekistan is eight times the rate in Latvia, while local income is falling behind. 'Sociological sur- veys conducted by the Uzbek Academy of Sciences have already recorded feelings of ethnic isolationism, negative views about other ethnic groups and in some places anti-Russian sentiments,' the report said. Ethnic rivalries are indeed simmering be- neath the surface.

Previous page

Previous page