ARTS

Exhibitions

Winners take all

Giles Auty

The Turner Prize 1988 Julian Schnabel (Waddington Galleries, till 23 December) If you want to win that badly,' my regular doubles partner remarked pleasantly to a tennis opponent who was attempting some rather questionable prac- tice, 'we needn't bother to play at all. We could simply say "you've won".'

I mean no disrespect to Tony Cragg, a perfectly honest man whom many believe to be a significant sculptor, by quoting once more from my extensive case-book of tennis aphorisms. Tony, as I forecast cor- rectly to those who asked me, was declared winner of this year's Turner Prize at a massive dinner held last week at the Tate Gallery. What I want to do is reflect a little not just on the nature of winning itself, in any wider scheme of things, but also on what success should be held to mean within the tight-frontiered world of art. Last week's occasion was hosted and the prize donated by Drexel Burnham Lambert, a Wall Street investment firm whose winning ways formed the subject of a less than favourable lead article earlier this year in The Spectator of 17 September. In view of this and of my known reservations about the handling of the Turner Prize in the four years since its inception, I suppose I was very lucky indeed to be invited to the occasion at all. It was noteworthy that art correspondents were not present in large numbers; indeed press facilities and in- formation about the whole affair have been decidedly modest, verging on non-existent. Perhaps we have reached a stage now when critical reaction is no longer thought neces- sary. In short, influential museum direc- tors, dealers and collectors can simply make up the rules of art as they go along, to an even greater extent than they do already. A winner can be declared when anyone feels the whim to do so, without fear of inconvenient comment or contra- diction. Obviously winning becomes sim- pler by such a route but its significance might be thought to be diminished.

This year, to create greater dramatic impact for the moment when the 1988 winner was finally announced, no short list of contenders or token representation of artefacts was on offer. This measure was designed also to protect the tender or merely petulant sensibilities of unsuccess- ful finalists, rather in the manner of an over-protective hostess at a children's par- ty: 'But I say everyone has won and you Julian Schnabel's 'Untitled', 1988, and Tony Cragg's blue plastic 'Policeman', 1988 shall all have a cake.' For my part, I suggest that those who cannot bear the suspense of being short-listed should take up some less robust profession. In fact, a titillating short list was finally offered during the address given by Nicholas Sero- ta, the new director of the Tate, at the ninth hour, between courses. Perhaps this was to reassure those assembled at dinner that more than one name really had been considered from the 90-odd nominations. The names of Lucian Freud, Richard Hamilton, Richard Long, David Mach, Alison Wilding and Richard Wilson (not the 18th-century landscape painter) had also been pondered over, apparently. In view of this it may seem surprising that the first-named, who towers not just head and shoulders but torso and at least one major leg-bone Aove the remainder, should not have carried off the doughnut. But to state this is to miss the point of the exercise, to the extent that there might be said to be one any longer. The correct conclusion to be drawn from the destination of the five Turner Prizes awarded so far and from the composition of all previous short lists is that the essence of this exercise is exem- plary: only artists of a certain generic type are included. We may think our culture is being led none too gently by the nose and we would be foolish to ignore the implica- tions of this.

Once again this year the rules for the Turner Prize have been changed subtly, this time to exclude all candidates other than practising artists. If this rule had been in force for the first four years, the short lists would look as follows: (1984) Richard Deacon, Gilbert & George, Howard Hodgkin, Richard Long, Malcolm Morley; (1985) Terry Atkinson, Tony Cragg, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Howard Hodgkin, John Walker; (1986) Art & Language, Victor Burgin, Gilbert & George, Stephen McKenna, Bill Woodrow; (1987) Patrick Caulfield, Helen Chadwick, Richard Deacon, Richard Long, 'Therese Oulton (winners' names italicised). You may notice that four sets of names recur in these lists when that of Tony Cragg, this year's winner, is included. It is also noteworthy that the 21 names which make up the winning and short-listed ranks include a high percentage of sculptors but not a single artist who works directly from life (e.g. Michael Andrews, Peter Greenham, Leon Kossoff or their younger counter- parts). Five different juries have come 'independently' to exactly the same conclu- son that the great realist/perceptual tradi- tion does not merit a mention, although it continues to account for a high proportion of all artistic practice both in painting and sculpture. Turner, whose name was pirated for this prize, was, of course, one of the greatest observers and interpreters of the natural world. Alan Yentob, the celebrity chosen to announce this year's prize- winner, emphasised that as an innovator Turner had been misunderstood and de- rided, as though this were some kind of apposite summary of the artist's life. Such historical superficiality provided an accu- rate reflection of the cultural tenor of the evening. In reality we were assembled to celebrate money and power rather than art. When I expressed mild disappointment at the general level of the speeches, a fellow diner asked me in amazement whether I were 'some kind of idealist'. Perhaps I was at the wrong party.

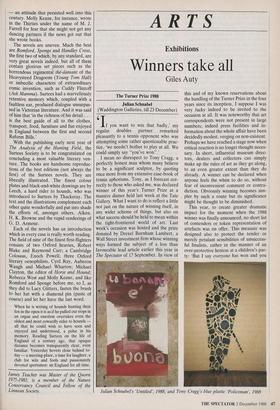

If the Turner Prize is exemplary in indicating the kind of art to make if one hopes for official sanction, that of Julian Schnabel at Waddington Galleries (2, 5 and 34 Cork Street, W1) illustrates the level at which to pitch artistic effort if one would be mega-rich as well. Nine of his vast productions, each bearing the legend 'La banana é buona', look as though they took roughly that number of minutes to produce, but then this young American giant is renowned especially for his fero- cious energy. Perhaps 'La mazuma é buona' would have made a more appropri- ate series title. Schnabel is a winner's winner, as the presence of Jack Nicholson at the artist's London vemissage testifies. Sylvester Stallone is another massive fan of the artist's genius. But it would be unfair to speak of Rambo meets Numbo when treat- ing of the numero uno star of the American gallery circuit; even his sneezes make headlines. Schnabel's series of portraits, which make up the remainder of the current show, are painted over layers of broken crockery. Whether the latter is the result of the artist's bullish exuberance or merely a relic of domestic disagreements I would not care to guess. The best thing is to see and marvel for yourself. Curiously, the hugely impressive bibliography of over 300 entries which is such a feature of the artist's catalogue omits dissenting voices such as that of Robert Hughes, one of the best critics working in America, and even my own mild reservations about the artist's Whitechapel exhibition of 1986. Real win- ners needn't bother with such trifles.

Previous page

Previous page