COMPETITION

Shayk-al-Subair

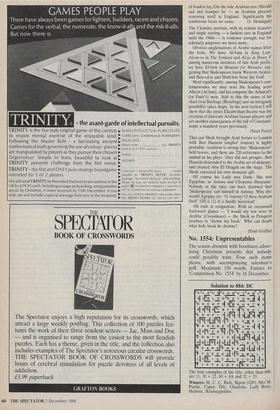

Jaspistos

In Competition No. 1551 you were asked for an extract from a doctoral thesis arguing that Shakespeare was an Arab.

A brave entry to a competition which taxed humorous ingenuity to the limit. D. Shepherd traced the Bard's origins to an Arab community known as the Beni Ing- lesi, descendants of civilians captured by Saladin after his victory at the Horns of Hattin in 1187 and sent to Damascus to set up an English-language school. John Sweetman argued that the 'Bacon theory' was developed by the enemies of Islam who chose the putative author because his very name was anathema to believers, and has since been supported mainly by Jesuits and Maronites. Among the cryptog- raphers, Basil Ransome-Davies anagram- matically extracted 'Wind no plots — I was Arab' from the first letters of Othello's dying speech. George Moor cleverly trawled the Sonnets for evidence of Shakespeare's pilgrimage to Mecca, but in his enthusiasm overran the word-limit.

The hard-working winners printed below get £15 each, and the bonus bottle of Cockburn's Late Bottled Vintage Port 1982, kindly presented by Cockburn Smithes & Co. Ltd, is awarded to P. I. Fell, who is lucky that he doesn't have to write the next chapter.

Even if there had not been numerous textual indications of the author's race and identity (who but a Bedouin of the desert would have had Portia choose rain as a figure of approba- tion, for example?), we should have learnt both of these from one hidden — though, when correctly interpreted, most explicit — message the author has left us. Let us break down into its constituent parts the revelatory stage-direction 'Exit, pursued by a bear' (Winter's Tale, III, iii): X: The author's identity, now to be made known.

Sit: 'Let it be' (sc, let it be understood to be'). Pursued: An obvious play on the adjective 'purse-hued' (the purse perhaps made of camel- skin), conjuring up vividly the brown face of our playwright!

By: The concept of authorship. A Bear: An anagram of 'ARAB E'.

The precise identity of `E', I shall reveal in my next chapter. (P. I. Fell) . . .unravel the mystery of Shakespeare's where, abouts between 1585 and 1592. I shall show how he sailed to Aleppo, and died there after a fight with Al'Khadwal, a brilliant young soldier-

scholar-poet, who quickly assumed his identity; how Shakespeare (alias Khadwal) reached Eng- land in 1587 and quietly set about perfecting his command of the language, and of his wife and father; how in 1592 rival playwrights, picking on the sun's shadowed livery he was proud to wear, reviled him as an upstart crow; how with initial success he grew careless (the horse he describes in Venus and Adonis is clearly an Arab, then hardly known in England); how he never again lowered his guard, babbled more of vasty wilds than of green fields, never used the name Arabella for a character, and allowed himself only a final joke — giving the name Cadwal to Cymbeline's disguised son . . .

(David Heaton) A rustic, poorly educated, English poacher shows a deep knowledge of medicine and mathematics, disciplines then peculiar to the Arabs. He knows the perfumes of Arabia, the thary horses and legal niceties. He makes a Moor the one true hero of his many brilliant playi, This is only feasible if one postulates Shakespeare's fleeing England for Venice, where he meets his double, a fair-skinned Arabian scholar. Shakespeare dies and his double arrives in London as William Shakespeare, an anagram of 'I am Sheik Elp al Waser', his real name. One contemporary pene- trated his disguise, describing him as 'a Tyger in a Player's hide' — the Hyrcanian tiger being an emblem of Arabia. He himself leaves the clearest clue in the poem beginning 'Let the bird of loudest lay,/0n the sole Arabian tree,/Herald sad and trumpet be' — an Arabian phoenix renewing itself in England. Significantly his tombstone bears no name. (J. Hennigan) The Chandos portrait, with its semitic features and single earring — a fashion rare in England until the 1960s — is evidence enough; but for scholarly purposes we need more.

Obvious anglicisations of Arabic names litter the texts. We have Al-bani in King Lear, Al-on-so in The Tempest and Al-ys in Henry V among numerous instances of this Arab prefix; we have El-bow in Measure for Measure, sug- gesting that Shakespeare knew Western Arabia; and Ben-ed-ic and Shah-low from the Gulf.

Most significantly, among Shakespeare's con- temporaries we may note the leading actor Alleyn (Al-lani), and his company the Admiral's (or Emir's) men. Add to this the name of his chief rival Burbage (Bourbagi) and an intriguing possibility takes shape. In the next section I will show that the entire Elizabethan theatre was the creation of itinerant Arabian bazaar-players and yet another consequence of the fall of Constanti- nople a hundred years previously.

(Noel Petty)

That our Sheik brought Arab horses to London with Ben Hussein (anglice Jonson) is highly probable: tradition is strong that 'Shakespeare' held horses, and there are 220 references to the animal in his plays. They did not prosper. Ben Hussein descended to the Arabic art of alchemy, and created Abu El Dragah on the stage. The Sheik exercised his own dramatic gift.

Of course his Lady was Dark. She was Egyptian, as Antony and Cleopatra illustrates. Nobody at the time can have doubted that 'Shakespeare' saw himself in Antony. Why else would Agrippa cry: '0 Antony! 0 thou Arabian bird!' (III.ii.12) It is hardly historical!

All ends in resignation. With an occasional backward glance — 'I would my son were in Arabia' (Coriolanus) — the Sheik as Prospero resolves to 'drown my book'. Who can doubt what holy book he drowns?

(Paul Griffin)

Previous page

Previous page