VACLAV! VACLAV!

IT'S ME, JOHN!

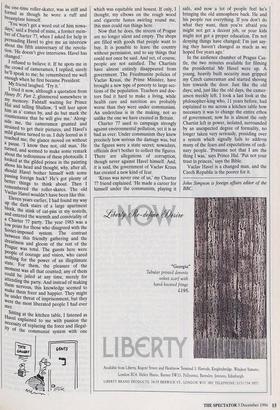

John Simpson expresses his dismay at the

slide into formal respectability of Vaclav Havel, the once-raffish Czech President

Prague THE CAMERAMEN rushed along the corridors of the Castle like a pack of dogs through the casbah, and I stumbled after them. Intricately carved double doors opened to let us pass; chandeliers lit our way; paintings of lost battles and petty tyrants glimmered out of huge gilt frames. As we passed, security men watched us wryly. In their badly cut uniforms and their soft, bunion-marked shoes, they represent- ed the true Czech spirit: informal, demot- ic, sceptical, stolid.

The Castle's pomp was created by the various imperial masters the Czechs have endured (with one brief 20-year respite of democracy and independence, which ended at Munich) ever since the Thirty Years War. That began with the Defenes- tration of Prague somewhere along these corridors in 1618, and the occupation endured with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hitler's Protectorate of Bohemia under Heydrich, and the vicious dictator- ship of Stalinism. Five years ago, the 'vel- vet revolution' — a journalistic phrase if ever I heard one — cleared the castle of the last exiguous remnants of foreign domination.

It was, I think, the most moving moment

of my life when I stool alongside Vaclas' Havel in November 1989 and watched the vast, hopeful, happy crowds in Wencesla.s Square. Through their peaceable deternation, they were ridding themselves of 369 years of subjection to others, the result of a single careless defeat at the White Mous' tam n in 1620; and they sang the hymn that the Czech scholar Comenius wrote soon after the battle: 'May the governing of your affairs/Come back at last to you/ MY nation.' Soon, his years of dissent and pet; secution over, Havel, now President, woulu gather his friends together and laugh at the pomposity of this beautiful, absurd Castle; and sometimes, as a particular joke, he would put on roller-skates to get around Its corridors faster.

In his first presidential speech, in Jai!' uary 1990, he said, 'Our country, if that IS what we want, can now permanently rad!' ate love, understanding, the power of spirit and ideas. It is precisely this glow that We can offer as our specific contribution t° international politics.' He was magnificent, The pack of cameramen reached a last carved mahogany door. A functionary whIs- pered, the doors were opened, and we flooded through. It was an audience chant' ber. Havel and his wife sat on gilt chairs with the President of Portugal and his wife' On the walls behind them hung portraits of 17th-century royalty; and President Havel, the one-time roller-skater, was as stiff and formal as though he wore a ruff and breastplate himself. YOU won't get a word out of him nowa- days,' said a friend of mine, a former mem- ber of Charter 77, when I asked for help in Persuading Havel to give me an interview about the fifth anniversary of the revolu- tion. 'He doesn't give interviews. Havel has changed.'

I refused to believe it. If he spots me in the crowd of cameramen, I replied, surely he'll speak to me; he remembered me well enough when he first became President. My friend laughed. 'Try it.' I tried it now, although a quotation from Henry rv, Part 2, glimmered somewhere in my memory: Falstaff waiting for Prince Hal and telling Shallow, 'I will leer upon him as a' comes by, and do but mark the countenance that he will give me.' Along- side me, the cameramen grunted and strained to get their pictures, and Havel's mild glance turned to us. I duly leered as it reached me; the glance moved on without a pause. 'I know thee not, old man.' He turned, and seemed to make some remark about the tediousness of these photocalls. I looked at the gilded prince in the painting above his head and thought, why, after all, should Havel bother himself with some Passing foreign hack? He's got plenty of better things to think about. Then I remembered the roller-skates. The old Vaclav Havel wouldn't have been like this. Eleven years earlier, I had found my way up the dark stairs of a large apartment block, the stink of cat-piss in my nostrils, and entered the warmth and conviviality of a Charter 77 party. The year 1983 was a low point for those who disagreed with the Soviet-imposed system. The contrast between this friendly gathering and the dreariness and gloom of the rest of the Prague was total. The guests here were People of courage and vision, who cared nothing for the power of an illegitimate state. For them, the pleasure of the moment was all that counted; any of them could be jailed at any time, merely for attending the party. And instead of making them nervous, this knowledge seemed to make them freer and happier. They might be under threat of imprisonment, but they were the most liberated people I had ever met.

Sitting at the kitchen table, I listened as Havel explained to me with passion the necessity of replacing the force and illegal- itY of the communist system with one which was equitable and honest. If only, I thought, my elbows on the rough wood and cigarette fumes swirling round me, this man could run things here.

Now that he does, the streets of Prague are no longer silent and empty. The shops are filled with goods that people want to buy. It is possible to leave the country without permission, and to say things that could not once be said. And yet, of course, people are not satisfied. The Chartists have almost entirely disappeared from government. The Friedmanite policies of Vaclav ICraus, the Prime Minister, have brought a new type of poverty to large sec- tions of the population. Teachers and doc- tors find it hard to make a living, while health care and nutrition are probably worse than they were under communism. An underclass is in the making, not so unlike the one we have created in Britain.

Charter 77 used to campaign strongly against environmental pollution, yet it is as bad as ever. Under communism they knew precisely how serious the damage was, but the figures were a state secret; nowadays, officials don't bother to collect the figures. There are allegations of corruption, though never against Havel himself. And, it is said, the government of Vaclav Kraus has created a new kind of fear.

'Kraus was never one of us,' my Charter 77 friend explained. 'He made a career for himself under the communists, playing it safe, and now a lot of people feel he's bringing the old atmosphere back. He and his people run everything. If you don't do what they want, then you're afraid you might not get a decent job, or your kids might not get a proper education. I'm not denying things have changed; I'm just say- ing they haven't changed as much as we hoped five years ago.'

In the audience chamber of Prague Cas- tle, the two minutes available for filming the presidential Mr Havel were up. A young, heavily built security man gripped my Czech cameraman and started shoving him towards the door. Just like the old days; and, just like the old days, the camer- amen meekly left. I took a last look at the philosopher-king who, 11 years before, had explained to me across a kitchen table how necessary it was to change the entire ethos of government; now he is almost the only Chartist left in power, isolated, surrounded by an unexpected degree of formality, no longer taken very seriously, presiding over a system which signally fails to address many of the fears and expectations of ordi- nary people. 'Presume not that I am the thing I was,' says Prince Hal. Tut not your trust in princes,' says the Bible. Vaclav Havel is a changed man, and the Czech Republic is the poorer for it.

John Simpson is foreign affairs editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page