BUT IS THE FORCE WITH HIM?

Alasdair Palmer interviews

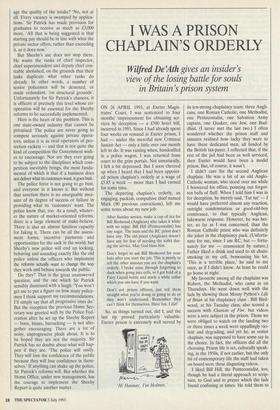

Sir Patrick Sheehy, who means to deliver a death blow to incompetence in the police

THEY USED to be called 'the Great and the Good', those men commissioned by government to report on public institutions in urgent need of radical reform. They were retired civil servants or academics, with a long record of public service behind them, who could be more or less guaran- teed, after a long, elegantly argued essay, to recommend that the government do precisely nothing. Times change. Sir Patrick Sheehy, whose report on the reor- ganisation of the police was published yes- terday, has recommended unequivocally that the Government do something about the police: his recommendations include lowering their starting pay and sacking inefficient officers.

The controversial character of the report derives from the controversial character of its author. Sir Patrick was knighted for his services to the tobacco industry — but there his record of public service stops. True, he saved BAT Industries — British American Tobacco as was — from the eviscerating embrace of Sir James Gold- smith and Kerry Packer — which counts as a public service by any standard. But his CV is not studded with those worthy com- mittees and appointments which make for the archetypal member of the Great and Good. He does not talk like one, either. A heavy smoker with a rough, gravelly voice, he sounds more like a boxer than a philosopher. When he spoke to me earlier this week, he gave the impression that he likes it that way. Sir Patrick has a marked preference for doing over talking, and for landing blows over pulling punches.

All the same, 40 years at BAT Industries is not the most obvious qualification for expertise in police matters. Why did Sir Patrick think he had been appointed? 'I don't know. Ask Kenneth Clarke. He appointed me.' But what did Sir Patrick think he brought to the party? What made him competent to pronounce on the police? 'I don't think I am specially competent. But the police service, as an organisation, has many of the characteristics of any other business: fundamentally, it needs to get the best out of its employees. And that's what I know about.' So the force would be bet- ter if it were run more like a multinational tobacco conglomerate? For once, Sir Patrick hesitated before giving his reply. `I'm not saying it should be run like BAT. What I am saying is that there should be some link between pay and performance. At the moment, there is none whatsoever.'

The determination to forge that link is what has produced the Sheehy Report's most radical recommendations. Automatic pay increases should be abolished. So should nationally fixed pay scales. No policeman should feel safe from the sack.

Even if his work is satisfactory, he should be sackable 'on structural grounds'. All new policemen should be placed on fixed- term contracts: ten years on recruitment, followed by a five-year deal after that. Serving policemen who are promoted or transferred should move to fixed terms too. Renewal should never be automatic. It should be up to the individual police- man to put in his application. In the sober words of the report: 'Management deci- sions on whether to grant one should be based on structural considerations, and the performance and conduct of the offi- cer concerned.'

None of that, however, should prevent a chief officer from firing anyone at any time 'on the grounds that the officer's retention would be injurious to the service'. In the world of business, the world of Sir Patrick Sheehy, this is absolutely standard manage- ment technique. In the British police force, last resort of Buggins's turn, it is heresy.

Placing the power to hire and fire direct- ly in the hands of chief officers means they have to have some way of monitoring their employees' performance. What is the best measure of a good cop? How many arrests he makes? How much the public likes him? How many convictions he gets? How much crime is reduced on his patch? It is a tough question, and the Sheehy Report was not set up to answer it. The report does, how- ever, give some ideas on how the task might be approached. The suggestions will delight every policeman who loves filling in forms. The proposed assessment papers run to ten pages and have over 30 different headings, including performance in terms of objectives, performance in terms of prin- cipal accountabilities, overall level of com- petence, overall assessment of performance — ranked as unsatisfactory, below satisfac- tory but improving, satisfactory, commend- able and outstanding. . .

It will be argued that assessment will impose yet another layer of red tape on the force, with more police time involved in assessing other policemen than in catching criminals. But Sir Patrick is unfazed. 'Look, every decent sergeant knows who on his team can do the job and who can't. It isn't difficult. When you formalise it, it looks bureaucratic, but the fact is assessment is part of every well-run business. It won't take up inordinate amounts of any manag- er's time.'

But it is essential for improving the stan- dard of police work. Everyone has had the experience of being stopped by a rude, aggressive policeman who looks about 19 years old and who acts as if he had rather be a member of the SS. Sir Patrick says he has been through that experience, 'though not since I started work on this report. Since then,' said Sir Patrick, without a trace of irony, 'the police have always been very courteous to me.' He maintains that the authoritarian bullying which can sometimes mar police behaviour is a consequence of poor training and bad management. There is at present no way to weed out officers whose characters do not fit them for police work. 'There's no incentive to be polite or even to do the job properly,' insists Sir Patrick. 'The rewards are exactly the same whatever the policeman does. If there is to be any improvement, that has to change.'

Sir Patrick also proposes to reduce — yes, reduce — police pay. He thinks it should be comparable with pay in middle- rank private sector jobs. For similar rea- sons, Sir Patrick proposes an increase in pay for senior policemen —just like British industry. But won't dropping a constable's starting pay from £15,000 to £10,000 dam-

age the quality of the intake? 'No, not at all. Every vacancy is swamped by applica- tions.' Sir Patrick has made provision for graduates to receive as much as £3,000 more. 'All that is being suggested is that starting pay should be in line with what the private sector offers, rather than exceeding it, as it does now.'

But Sheehy's axe does not stop there. He wants the ranks of chief inspector, chief superintendent and deputy chief con- stable abolished, on the grounds that their tasks duplicate what other ranks do already. In other words, a number of senior policemen will be demoted, or made redundant, 'on structural grounds'. Unfortunately for Sir Patrick's chances, it is officers at precisely this level whose co- operation will be essential for the Sheehy reforms to be successfully implemented.

Here is the heart of the problem. This is one state-owned industry that cannot be privatised. The police are never going to compete seriously against private opera- tors, unless it is as rival operators of pro- tection rackets — and that is not quite the kind of competition the Government wish- es to encourage. Nor are they ever going to be subject to the disciplines which com- petition inevitably brings, the most funda- mental of which is that if a business does not deliver what its customers want, it goes bust.

The police force is not going to go bust, and everyone in it knows it. But without that sanction there is no unarguable mea- sure of its degree of success or failure in providing what its 'customers' want. The police know that, too. As a result, whatev- er the nature of market-oriented reforms, there is a large element of make-believe. There is also an almost limitless capacity for faking it. There can be all the assess- ment forms, incentive payments and opportunities for the sack in the world, but Sheehy's new police will end up looking, behaving and sounding exactly like the old police unless the officers who implement the reforms actually want to change the way they work and behave towards the public.

Do they? That is the great unanswered question, and the one which Sir Patrick sensibly dismissed with a laugh. 'You won't get me to put a figure on how many police- men I think support my recommendations. I'll simply say that all progressive ones do.' But the reception the previous Home Sec- retary was greeted with by the Police Fed- eration after he set up the Sheehy Report — boos, hisses, barracking — is not alto- gether encouraging. There are a lot of noisy, unprogressive plods about. It is to be hoped they are not the majority. Sir Patrick has no doubts about what will hap- pen if they are. 'The police will ossify. They will lose the confidence of the public because they will lose confidence in them- selves.' If anything can shake up the police, Sir Patrick's reforms will. But whether the Home Office, under new management, has the courage to implement the Sheehy Report is quite another matter.

Previous page

Previous page