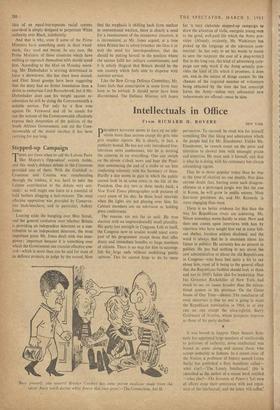

Intellectuals in Office

From RICHARD H. ROVERE

NEW YORK DRESIDENT KENNEDY seems to turn up on tele- r vision more than anyone except the girls who give weather reports. He is clearly, in fact, a publicity hound. He has not only introduced live- television news conferences, but he is inviting the cameras in on everything. One can switch on the eleven o'clock news and hear the Presi- dent announcing the end of a strike or see him conferring solemnly with his Secretary of State. Hardly a day seems to pass in which the public cannot look in at some event in the life of the President. One day two or three weeks back, a New York Times photographer took pictures of every event of his day. In those brief intervals when the lights are not playing over him, his Cabinet members are on television or holding press conferences.

The reasons are not far to seek. He won election with an unprecedentedly small plurality. His party lost strength in Congress. Left to itself, the Congress now in session would reject every part of his programme except those that offer direct and immediate benefits to large numbers of citizens. There is no way for him to accomp- lish his large ends without mobilising public ( opinion. This he cannot hope to do by mere persuasion. To succeed, he must win for himself something like that liking and admiration which the people had for Mr. Eisenhower. Unlike Mr. Eisenhower, he cannot count on the press and television to shower him with unsought praise and attention. He must seek it himself, and that is what he is doing, with his customary but always astonishing vigour.

That he is more popular today than he was at the time of election no one doubts. Nor does anyone doubt that, barring sonic such disagree- ableness as a prolonged jungle war like the one in Korea, he will grow in public esteem. Most first-term presidents do, and Mr. Kennedy is more engaging than most.

There is no better evidence for this than the way his Republican rivals are scattering. Mr. Nixon nowadays seems hardly to exist. Now and then one comes upon interviews with him by reporters who have sought him out in some fall- out shelter, location seldom disclosed, and the word is always that he is uncertain about his future in politics. He certainly has no present in politics. He has had nothing to say about the new administration or about the old Republicans in Congress—who have had quite a bit to say about him, most'of it being to the general effect that the Republican faithful should look to them and not to 1960's fallen idol for leadership. Nor has Governor Rockefeller of New York had much to say on issues broader than the educa- tional system in his province. On the Great Issues of Our Time—silence. The conclusion of most observers is that no one is going to want the Republican nomination in 1964, or at any rate no one except the ultra-rightist, Barry Goldwater of Arizona, whose prospects improve as those of his party decline.

It was bound to happen. Once Senator Ken- nedy has appointed large numbers of intellectuals to positions of authority, some intellectual was bound to come along and accuse those who accept authority as Judases. in a recent issue of the Nation, a professor of history named Loren Baritz has published a fiery manifesto called— what else?---'The Lonely Intellectual.' (He is identified as the author of a recent book entitled --what else?--The Servants of Power.) 'Let men of affairs cease their annoyance with and repul- sion of the intellectual, and the latter will suffer,' he writes. I cannot state it as a fact that Mr. Baritz has spent the last eight years complaining about the contempt for ideas in the United States, and Citing Dwight D. Eisenhower as the most con- temptible of the contemptuous, but I'll bet he has spent part of his time doing that, and I know that the magazine for which he writes has been full of such complaints and citations, as have most of our intellectual trade journals. It would have, been logical to conclude, from all that has been said on the subject in recent years, that the intellectual community would welcome the elec- tion of a President who qualified as an intellec- tual himself and who had enough respect for the breed in general to put large numbers in his government. And in point of fact a large part of the intellectual community is delighted. But Mr. Baritz represents what is certainly a sizeable minority within the group and one that has at various times in recent American history been a majority.

Its mode of reasoning is odd. `Let the intellec- tual be absorbed in society,' Mr. Baritz says, 'and he runs the very grave risk of being digested by it.' And more: 'When he touches power, it will touch him.' On matters other than those having to do with risks of being digested by society or touched by power, it has always been the position of the intellectuals—particularly those of the' avant-garde, about whom Mr. Baritz is so con- cerned—that the life of the mind involved heavy risks and that no one should fear experience that might be corrupting as well as instructive.

At the moment, one of the heroes of Mr. Baritz's cult is a novelist of odd and unpredict- able ways whose life is a quest for experience of every sort. He has written at length of the need for adventure and experimentation with sex, nar- cotics, and even violence, and in a particularly adventurous and experimental mood not long ago, he practised a bit of violence on his wife, with a knife. Explaining himself to the police and to psychiatrists, he put forward a quite sophisticated rationale, and while his friends and admirers did-not entirely accept it, they gave it a kind of solemn -credence that they would never have extended to a knifer with a low IQ. But if he had taken a job as Deputy Under-Secretary of the Interior, and explained that he found something quite tangy in a brush with power, he would have been drummed out of the regi- ment. He would have been reminded of Mr. Barites absolutely irrefutable logic—When he touches power, it will touch him.' Naturally, the lonely intellectual dreads being touched.

Previous page

Previous page